A shortened version of Jonathan Bardon’s definitive tome, A Short History Of Ulster provides a comprehensive account of the province from the earliest settlements nine thousand years ago to the turmoil of The Troubles, and the fragile peace period that followed.

The UWC strike of 1974 succeeded only because the great majority of adult male Protestants were in work and were confident that their jobs were secure. That confidence was misplaced: the region had become more dependent on cheap oil than any other part of the United Kingdom and the blow delivered by the international quadrupling of energy prices, therefore, was acutely felt.

The rapid growth of synthetic fibre production had been Northern Ireland’s best success story, accounting for one third of the United Kingdom’s output by 1973. The industry was concentrated in the protestant heartland of south County Antrim and, for example, provided nearly three quarters of all manufacturing jobs in Carrickfergus.

Now Northern Ireland suffered more than any other part of the United Kingdom: many firms were pushed towards the edge by the sudden rise in transport costs, as well as the leap in the price of electricity, nearly all of it generated in Northern Ireland from imported oil.

Then in 1979 the economy of the western world took a downward plunge and by the second quarter of 1980 this depression was leaving a trail of devastation in Northern Ireland. Between 1979 and the autumn of 1981 no fewer than 110 substantial manufacturing firms in the region closed down. When Grundig finally shut the doors of its prestigious Dunmurry plant in 1980, one of the reasons given by the management for doing so was the existence of ‘disturbances of a political nature’. Generous inducements notwithstanding, the continuing violence frightened off overseas investment.

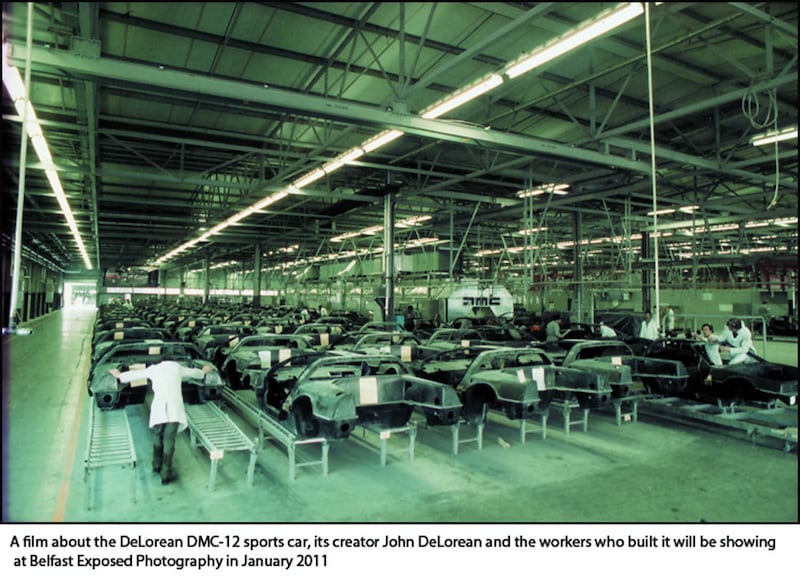

It was not violence, however, that was mainly responsible for turning economic decline into a crisis. This depression, the worst since the 1930s, was precipitated by another leap in oil prices and in Northern Ireland this sealed the fate of most of the remaining synthetic fibre plants. The region’s fragile economic base was in danger of cracking apart and nothing demonstrated this more than the foundering of the Government’s flagship project, the De Lorean sports car factory in Dunmurry in May 1982. In the same year Goodyear closed its Craigavon factory with the loss of 773 jobs.

Fewer than 9,000 cars rolled off the production line at the original DeLorean plant in Dunmurry.

Fewer than 9,000 cars rolled off the production line at the original DeLorean plant in Dunmurry.

Altogether forty thousand manufacturing jobs disappeared in the decade between 1979 and 1989. This protracted shake-out removed most of the branch factories of British and overseas multinationals, thus leaving the industrial sector once again dominated by the older indigenous firms.

East Belfast shipyard Harland and Wolff

East Belfast shipyard Harland and Wolff

The linen industry’s decline had been steep since 1959 when forty-four mills across Northern Ireland had kept forty-five thousand in employment. By 1983 only 6,000 were employed, but thereafter the industry retained a significant, if precarious, niche in a specialised international market. Harland and Wolff, making losses every year since 1964, was saved from closure only when the Stormont government took shares and wrote off losses in 1971. The erection of two great cranes, Goliath and Samson, and the launch of several supertankers gave every indication that all was well but the company’s position became desperate with the market collapse in 1974 and it obtained £350 million from the exchequer between 1977 and 1986.

In the early 1980s Short Brothers bypassed Harland and Wolff to become Ulster’s biggest manufacturing concern. The most profitable division manufactured armaments; most employees, however, were engaged in making small civil aircraft. Official statistics generally placed both Harland and Wolff and Short Brothers in the private sector but both were wholly owned by the Government and utterly dependent on massive subventions from the exchequer. Then in 1989 the Government privatised both companies, which cost the taxpayer £1,486 million.

‘More money for these people?’ Margaret Thatcher said to Garret FitzGerald when he suggested seeking European contributions for the International Fund for Ireland. “Why should they have more money? I need that money for my people in England.” In fact she drew back from the consequences of applying undiluted Thatcherism to Northern Ireland, and Ian Aitken, writing in the Guardian 26 July 1989, referred to the region as ‘the Independent Keynesian Republic of Northern Ireland, where monetarism remains unknown’.

Margaret Thatcher and Irish Premier Garret Fitzgerald in 1985

Margaret Thatcher and Irish Premier Garret Fitzgerald in 1985

Exceptional efforts to attract new investment brought paltry returns in the harsh economic climate of the 1990s and Northern Ireland had all but ceased to be a manufacturing region. Its economy had in effect become a service economy: the public sector gross domestic product had risen to 44 per cent of the whole by 1986 – a development only made possible by the British subvention, money transferred by Westminster over and above the sum raised in taxation in Northern Ireland, which reached £4 billion by 1993.

The bulk of the subvention was spent neither on direct aid to industry nor on the security forces. The overwhelming share was assigned to the public services and the most visible sign of this expenditure was the transformation of the region’s public housing – not only a vital stimulus to the economy but also a major attempt to ease intercommunal tensions.

By the time that republican and loyalist paramilitaries had called their ceasefires in the autumn of 1994 there were thirteen ‘peace lines’ in Belfast, their location decided on by the security forces and the Northern Ireland Office. The earliest one to be put up was at Cupar Street, a grim and formidable barrier of concrete reminiscent of the Berlin Wall marking the volatile divide between the Protestant Shankill and the Catholic Falls. Later barriers, made of curving brick walls surrounded with shrubs, were almost architecturally pleasing. The peace lines were a visible sign that housing a divided community presented exceptional problems requiring exceptional measures.

The Peaceline near Cupar Way. Picture Mal McCann.

The Peaceline near Cupar Way. Picture Mal McCann.

In August 1969 the Westminster and Stormont governments agreed to strip all control of public housing away from local councils and transfer it to a regional authority, the Northern Ireland Housing Executive. Then, in 1973, twenty-six district councils replaced the former complex local authority structure, their functions drastically limited by comparison with their predecessors and their counterparts in England, Scotland and Wales. Intimidation, intercommunal violence and enforced population movement ensured that the most urgent task was to attend to the housing needs of the people. By 1976 the total number of houses in Belfast destroyed or damaged in the violence reached 25,000. The Housing Executive began its task, in the words of a government minister, as ‘the largest slum landlord in Europe’. A House Condition Survey of 1974 revealed the scale of the problem. In Northern Ireland as a whole 19.6 per cent of the total dwelling stock was statutorily unfit, compared with 7.3 per cent in England and Wales.

Having created a great bureaucratic machine, the governments in Westminster showed a growing reluctance to pay for the new dwellings the region so desperately needed. It was not until 1981, when the political situation seemed especially bleak, that the Government made housing its first social priority. By the mid-1980s the Housing Executive was able to spend around £100 million a year on its capital programme. Between 1982 and 1991 it had spent £2.4 billion on new dwellings, maintenance, grants and renovation. Houses were allocated with scrupulous impartiality, a task made acutely difficult because the continuing Troubles caused both Protestants and Catholics to seek safety in numbers: for example, Catholics clustered in older housing in west and north Belfast, creating intense pressure there.

Nevertheless, the vigorous drive to upgrade Northern Ireland’s housing may have contributed significantly to the notable fall in levels of violence in the region in the 1980s by comparison with the 1970s. By the early 1990s it could be said that Northern Ireland’s housing crisis was over, though the sale of council houses, the rundown of the Housing Executive and the rise of housing associations meant the partial abandonment of earlier commitments to make dwellings available on the criterion of need.

Better housing, though it did much to banish rioting from the streets, did not encourage Catholics and Protestants to live more closely together; indeed, by the middle 1990s, 90 per cent of people living in 90 per cent of electoral wards were of one religious persuasion. Northern Ireland’s society was as polarised as ever, in part a consequence of protracted violence which escalated at the beginning of the century’s last decade.

The cover of A Short History Of Ulster, by the late Dr Jonathan Bardon

The cover of A Short History Of Ulster, by the late Dr Jonathan Bardon

A Short History Of Ulster is by Dr Jonathan Bardon, a former lecturer at Queens University, Belfast. In 2002, he was awarded an OBE for his ‘services to community life’ in Northern Ireland. Jonathan died in 2020. It is published on August 28 by Gill.