Illustration by Roy Scott / Ikon Images

The Isle of Dogs occupies a southward kink in the River Thames, the tear drop of the East End. It twinkles with the steel and glass of Canary Wharf’s office skyscrapers and high-rise flats reflected in its docks. I recently wandered around what’s known as the Digital Docklands, an estate of data centres overlooking Millwall Dock.

The water that once powered a third of London’s grain imports from ships arriving here from Europe, Australia and New Zealand is being put to new use – piped around racks and racks of servers to keep them cool. In 1858, Isambard Kingdom Brunel’s steamship the SS Great Eastern, the biggest ship ever built at the time, launched here. Today, the big industrialist in town is a San Francisco-based property giant called Digital Realty, which owns the 119,000-square-foot site.

Cast-iron disused cranes stretch skywards over the dock – silent beneath the thick hum of the data centre. It is a fortress of cladding and faux-wharf redbrick, and its windows reveal tubes pumping dock water around tight rows of oblongs. If data exists in the cloud, then this is its body and blood.

There are at least 20 data centres – which house computing systems that store and process data – in the Isle of Dogs and South Poplar area, one of the highest concentrations in Britain. They are a “severe” risk to housebuilding for the next decade, according to Tower Hamlets Council housing department documents uncovered by the online magazine, London Spy: “Housebuilding, at scale, is unable to proceed for potentially ten [or more] years due to lack of available electricity capacity” because of a “sudden increase in connection applications from data centres”. (A Tower Hamlets Council spokesperson told me they were “not aware” of this, but acknowledged the need for more electricity capacity in the “next decade” and Thames Water improvements for “future growth”.)

Data centres use a vast amount of water and electricity. Just saying “thank you” to ChatGPT four times in an exchange with the AI chatbot uses up the equivalent of a glass of water. In fact, one data centre can use as much energy as thousands of homes. Helen Wakeham, the Environment Agency’s director of water, entreated the public over the summer to start “deleting old emails” in order to save water. “When we think of using Netflix, Zooming, posting things on TikTok, we think, ‘It’s digital, it doesn’t have a footprint, it’s on the cloud,’ but it actually has a very physical presence,” said Felicia Liu, an expert on the material impact of data centres, at the University of York.

In the Docklands area, data centres use up to 75 per cent of the electricity, compared with just 6 per cent used by houses. The Isle of Dogs is a deprived place, where Sixties council flats crumble beneath the Gotham City of finance above them. There is an acute need for more houses here, but data centres are booming because of demand for storage and internet speed from Canary Wharf.

Housing is under threat elsewhere, too. Three west London boroughs – Hillingdon, Ealing and Hounslow – faced a de facto ban on new homes in 2022 because of data centres straining the local electricity grid. Housing delays in Slough have also been blamed on data centres: the Berkshire town is home to Europe’s largest hub of them. A recent major review into Britain’s water industry hinted at this competition for resources, highlighting the need for infrastructure to serve “critical areas such as housing and data centres”.

Subscribe to The New Statesman today from only £8.99 per month

The government has a policy to create “AI growth zones” but is already facing local campaigns and legal challenges against building data centres on the greenbelt. This follows a global pattern of protest and opposition to data centres in Ireland, the US, the Netherlands and South America.

Brits are the most likely nationality in Europe to pick the wrong definition of a data centre from a multiple choice of four, according to a 2024 survey. This poor understanding, coupled with a lack of local consultation on where they’re built, could be a problem for “economic development and community harmony”, warned Liu. “Involving the community is going to be really important – rather than creating an image of this massive data centre receiving lots of investment where profit is either going back to the shareholders or the bosses in Silicon Valley and not benefiting the local community.”

Plans to build Europe’s largest data centre in the tiny village of North Ockendon, the easternmost part of the capital, lying alone outside the M25, have drawn opposition from eco-activists and Reform politicians alike. This is greenbelt ground zero: the land of the golf club and parish church, badgers and harvest. “There’s already a lot of mistrust of politicians here, and in the national picture, and this is the kind of thing that’s making it worse,” said Ian Pirie of Havering Friends of the Earth.

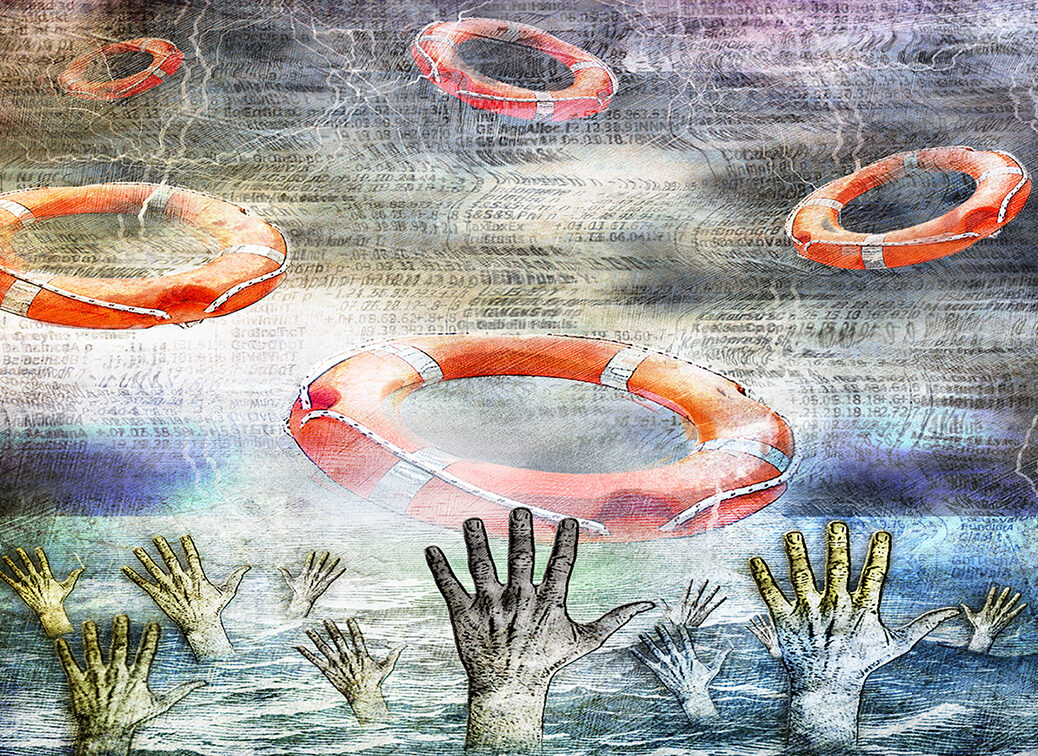

Labour could be facing a painful coalition of Yimbys and Nimbys, as data centres impact both housebuilding and the environment. Such schemes are almost perfectly designed to expose Britain’s weaknesses: ageing water infrastructure, the creaking National Grid, a housing deficit, planning snarl-ups and neighbourhoods buffeting in the slipstream of globalisation. We may fear the robots stealing our jobs, but what if they’re coming for our houses too?

[See also: Labour can’t agree on how to fight Farage]

Content from our partners