Wednesday 27 August 2025 3:56 pm

| Updated:

Wednesday 27 August 2025 5:06 pm

Share

The ‘customer’ in the fried chicken shop didn’t touch his meal. Instead, he photographed the kitchen door’s keypad and left. ‘Corporate spy,’ muttered the cashier before showing me three identical incidents caught on his security cameras.

This is the opening line of a pitch I received from a writer called Joseph Wales, entitled “London’s Fried Chicken Wars: Espionage, Betrayal and Social Media Sabotage.”

Wales promised that after “six weeks of undercover investigation” he could shine a light on the murky, sometimes violent world in which temporary staff turn out to be spies from rival chains, social media feeds are regularly flamed by troll armies and fake mystery shoppers plant dead flies in rival stores.

These claims could be backed up, he said, by FOI requests to local councils, screenshots from private Whatsapp groups and police reports linking chicken shops from Brixton to Tottenham with organised crime. He even claimed that, during his investigation, a restaurant manager handed him a napkin with a scrawled warning: “Be careful who you eat with.”

It’s the kind of pitch that grabs you by the shirt collar. It has it all: colour, characters, a sense of place. It examines something niche but speaks to something wider. The only problem? It was completely made up.

It’s the kind of pitch that grabs you by the shirt collar. The only problem? It was completely made up

It didn’t take long for alarm bells to start ringing. Why would a restaurant manager write his sinister message on a napkin, where it could be used as evidence, rather than simply growling it in a menacing fashion? Wales claimed he was sitting in a branch of Chicken Cottage in Stratford – but there is no Chicken Cottage in Stratford. The more I looked into the story, the more absurd it all seemed.

I went back through the pitch and immediately spotted the tell-tale signs: numbered headers divided into bullet points. Pertinent words bolded up. Em dashes scattered liberally throughout. This was the work of AI. When I called him out on this, Wales admitted using AI in his pitch but assured me he would never use it to write or research his stories. I asked him to jump on a call: radio silence.

Usually at this point I would delete the pitch and move on. But there was something about Joseph Wales that niggled at me, a feeling that there was more to this story. So I started to dig. And soon this bogus pitch about warring London chicken shops had led me on a trail across the globe, from East Africa to Chicago, revealing a bigger, sadder story about the lives we lead on the internet. It’s a story about how AI is coming for people’s jobs – and how those people are using AI to fight back. But most of all it’s about how AI isn’t only changing the world: it’s also making it the same, but more.

At first I thought Joseph Wales was the villain of this story but the more I learned, the more he began to seem like its anti-hero, a man hustling and flailing in the face of generational change. And, like all good thrillers, the real villain wouldn’t reveal himself until the final act.

Who is Joseph Wales?

So what was the deal with the pitch? My first hypothesis is what I’ve come to think of as the ‘Oobah Butler theory’: that the AI chicken shop story was deliberately placed for the purposes of making me look silly, for journalism! I can imagine moon-faced gonzo journalist Butler, most famous for taking a made-up restaurant called The Shed (actually his parents’ shed) to the top of Tripadvisor’s list of the best London restaurants, struggling to stifle a grin as he explains to camera how he tricked some foolish editor into publishing his concocted story.

But if it was a prank, the prankster was playing the long game: Wales has a modest online presence dating back years, including a portfolio and a website. His cuttings are made up of copywriting gigs covering financial advice (“Best Way to Invest 20k in 2025”) and pest control (“What does a bat bite look like?”). Some of his posts are, according to fairly rudimentary detection tools, at least partly written by AI. His WordPress site contains a handful of unremarkable blog posts about SEO writing: “Imagine you could get your search traffic to hang on your every word…”

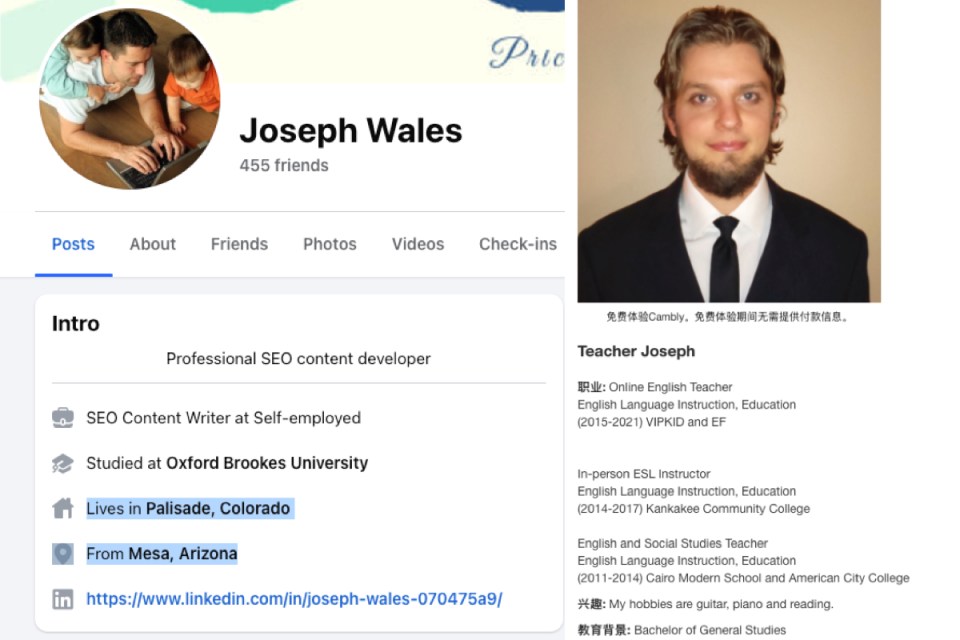

The resumé he sent me says he is currently based in Los Angeles and studied business administration at Oxford Brookes University. A reverse image search of the headshot from his portfolio comes up with just one match: a profile on Cambly, a website that links language students with tutors. He is listed as “Teacher Joseph” and there is an accompanying video of a cheerful looking, bearded white man with an American accent saying he is “from Chicago in America”. Teacher Joseph apparently studied at Cairo Modern School from 2011-2014, which clashes with the dates my Joseph says he studied in Oxford.

On the hunt for Joseph Wales

On the hunt for Joseph Wales

Joseph Wales’ email sign-off and CV list two different American phone numbers: one is disconnected, the other just rings out. The first originates from east Michigan and the second is from 1,000 miles away in Bartlesville, Oklahoma. Links to his profiles on Discord and LinkedIn are dead.

I keep digging and find a different Joseph Wales on Facebook who works in SEO and did go to Oxford Brookes but this one says he lives in Palisade, Colorado. A reverse image search for this Joseph points to a stock image used commonly across the internet. Promisingly, this Joseph follows several freelance writing networks of the kind that occasionally repost my callouts for writers.

Next I follow up the references from his CV. These mostly consist of big international copywriting agencies, who I email with little hope of getting a response. One stands out, though: the WayneGlance Writing Agency, which does not appear to have an online footprint.

I am about to call it a day when I notice Joseph’s email address: “miminiwriter”. I search for “mimini” and not much comes up. I try various permutations of those letters and “mimi ni” (with a space) gives me a clue: it means “I am” in Swahili. “I am writer”. This matches another tantalising nugget from his resumé: a “professional affiliation” with the NCCK – the National Council of Churches of Kenya.

A search for “WayneGlance Kenya” points me towards a Kenyan jobs website featuring a CV with identical wording to the resumé of my Joseph Wales. It belongs to someone based in Nairobi: I have found my man.

The Margaux Blanchard incident

I email my findings to Wales, not to berate him but because I’m not sure who else would be interested. I’ve spent so many hours trying to work out who he is that I’m starting to quite like the guy. He is a grifter, sure, but he knows a good pitch, and he could tell you what to do if you discover a snake’s nest on your property, which sounds like a useful life skill. He doesn’t reply.

As an experiment, I feed ChatGPT the last few issues of this magazine and ask it to come up with some features: it immediately spews out two ideas that are worryingly close to stories I’ve been thinking about writing. I wonder how many pitches I’ve accepted that originated in the digital mind of an LLM.

I reach out to a few fellow editors and discover that I am not alone in receiving AI-generated pitches. One desk head at a major British tabloid says “a blizzard” of AI pitches “arrive with depressing inevitability.” She forwards me a press release so anodyne it couldn’t possibly have been written by a human. Nobody I speak to has received anything quite as audacious as Joseph’s chicken shop pitch.

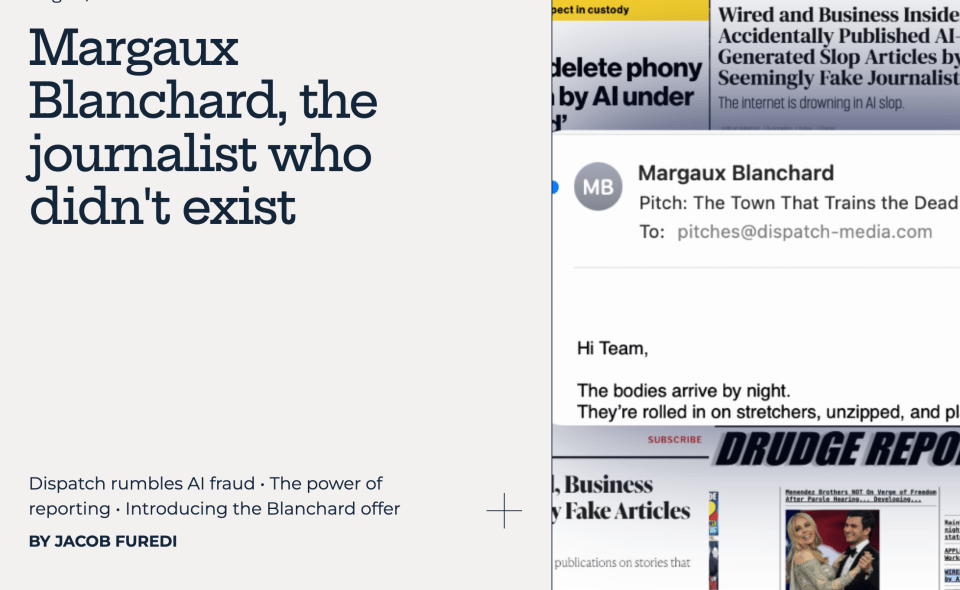

Then the journalist and broadcaster Sonya Barlow, who I’d spoken to for this story, sent me an email with the words “Might be of interest…” with a link to a story in the Press Gazette: the now infamous Margaux Blanchard scandal in which AI pitches became AI articles that were published in respected publications including Wired and Business Insider.

This was a bombshell moment for British journalism. Dispatch Media journalist Jacob Furedi, who broke the story, had himself received a macabre pitch from Blanchard about a decommissioned mining town in Colorado called Gravemont that she said was being used as an underground training facility for forensics teams and first responders.

“The bodies arrive by night,” went the pitch. “They’re rolled in on stretchers, unzipped, and placed in the mock apartments, classrooms, and bus stations.”

Like my chicken shop story, it was an irresistible pitch. And like my chicken shop story, it was entirely fabricated by AI. Gravemont, Colorado doesn’t even exist. But unlike Joseph Wales, Blanchard appeared to be a respectable journalist. She had written a charming story for Wired about couples getting married inside the world of Minecraft (Wired had already removed the piece after getting suspicious over the unorthodox way Blanchard had asked for payment).

Business Insider, meanwhile, had run a pair of essays by Blanchard entitled “Remote work has been the best thing for me as a parent but the worst as a person” and “I had my first kid at 45. I’m financially stable and have years of life experience to guide me.” Other publications carrying her articles include SF Gate and Index on Censorship magazine.

I search my emails for “Margaux Blanchard” and get a little hit of dopamine when I find a result. A pitch from 21 June entitled London’s Silent Raves Are the New Status Gyms. “This feature would look at the rise of silent dance parties doubling as fitness classes—happening in parks, rooftops, even under train arches—where participants wear wireless headphones and vibe out together to curated DJ-led workouts. It’s sweaty, spiritual, and extremely Instagrammable. But here’s the twist: I’d position it as the new status symbol for the wellness-obsessed and burnout-weary.”

This is the first time I’ve received a story that’s just blatantly what you might call an AI hallucination.

She offered to write 1,200 words “with that slightly cheeky City AM voice”. It’s a terrible pitch – I’m slightly jealous she saved her best ideas for other publications – and if I ever opened the email, I immediately forgot about it. I reply telling her I love it. She never responds.

I do some more digging. The headshot associated with Blanchard’s Gmail account – margauxblanchard414 – is a lady in her fifties with a neat bob. I’m almost certain it’s a picture of the French-American author Mireille Guiliano, who wrote the 2004 book French Women Don’t Get Fat (as far as I know she has absolutely nothing to do with this story).

“This is the first time I’ve received a story that’s just blatantly what you might call an AI hallucination,” Furedi would later tell me. The thing neither of us can work out is the why of it all. “I would love to know what’s the motivation,” he says. “Business Insider don’t pay very much for that sort of lifestyle op-ed slop. There must be an easier way to make money.”

Furedi thinks the big losers could be newer, younger freelance writers. “It’s obviously irritating for editors and it’s discourteous to readers, but it’s a real shame for freelancers. There might be a tendency for editors to just use people they already know and trust.”

I’m mulling over what all this means for my AI story when – record scratch – I get a reply from Joseph. “I was just going through your emails and I can’t help myself from smiling,” he says. I tell him I want to talk to him and he asks why. I say I want to find out who he really is. “Alright, brace yourself for the truth!” he says. “It’s about time I shared this… You’ll definitely have a field day… Of course, there’s a story behind everyone.” He signs off with a winky face.

A beautiful afternoon in Nairobi

It is a glorious afternoon in Nairobi. The sun is dazzling blue against the green of the garden where the man I have known as Joseph Wales is sitting with three of his dogs – “I have so many dogs, bro” – all sturdy mongrels who occasionally jump up at him for strokes. In the background I can see squat brick houses and tropical vegetation. This is the suburb where he lives with his wife and the two young girls he has just dropped off at school. “They are very pretty,” he says with pride. “And they have my brains.”

After several false starts and some fraught negotiations (I ended up wiring him £20 out of my own bank account as a “token”), we connected over Google Meet. Wales, it is immediately clear, is not the jovial white bloke “from Chicago in America” but a slim black guy “born and bred” in Nairobi to a Kenyan mother and a British father, who he says works for the Kenyan air force. He speaks good English with a thick, friendly accent. He’s wearing a tracksuit top and a black Covid mask, which he says is to cover a fat lip he suffered during a recent car accident.

The first revelation is that his name is not Joseph Wales, it’s Wilson Kaharua. “I told you, I have a long story to tell!” he laughs. I ask him to start at the start. He tells me he’s always been interested in technology. As a boy he would read about the phishing scams that originated in Nigeria, which was years ahead of Kenya when it came to online culture, although he says he’s never tried anything like that himself.

Finally a picture of the real Joseph Wales – or is that Wilson Kaharua?

Finally a picture of the real Joseph Wales – or is that Wilson Kaharua?

He studied economics and finance at Kenyatta University, “one of the best in my country”. After graduating in 2011 – which would put him in his mid thirties – he worked as a tutor helping language students write essays and also “worked at a few banks”. But he says “the money they were paying me was not enough” so he began applying for international copywriting assignments. Among the first was for a British company that sold industrial lighting. The owner’s name was Joseph. “He taught me the ropes. He was the one who taught me who I am… before I started teaching myself. I have a lot of gratitude for him.”

When Joseph died of a brain tumour, Wilson took his name, reasoning that English language publications would be more comfortable with an English-sounding name. Why “Wales”? He just liked the sound of it. The picture he uses on his website was just something he found online: “It was someone who looks almost like me,” he says (in fact, it would be hard to imagine two people who look less alike).

Read more

UK Heatwave 2.0: 8 best London restaurants with outdoor dining terraces for summer

By 2015, Wilson was working for a number of big copywriting agencies. The pay wasn’t great by British standards but it went pretty far in Nairobi. “I was making good money,” he says. Much of his work appeared without a byline but some – like the pest control articles – appeared under “Joseph Wales”.

I ask how he managed to get paid when his byline didn’t match his bank account. “That’s very easy,” he laughs. He says some of the companies paid him in crypto but for the rest he simply bought a fake drivers’ licence off the dark web and registered a Paypal account under Joseph Wales. I ask about the American phone number on his CV: he says he pays $3.99 a month for it and it reroutes to his phone in Kenya.

Drone footage of Wilson’s Nairobi village

Drone footage of Wilson’s Nairobi village

Things were going well for Wilson Kaharua. Money was rolling in and his alter-ego Joseph Wales seemed to have everyone fooled. But then, in 2023, the bottom dropped out of this carefully constructed world: “AI replaced us.”

Suddenly there was no need to pay people like Wilson to write about bat bites and snake nests – AI can do that for free in a few seconds. So what’s a guy to do? “I’m not liking AI but I started to study it every day,” he says. “You have to work with it because it’s not going anywhere and we can’t do anything about it.”

Wilson paid to subscribe to a service that would alert him to callouts for pitches: callouts like the one I made on X asking for “big, bold, fun, weird” ideas. Using DeepSeek, Wilson generated a pitch that would be perfect for this magazine. “If you were not smart enough, it would have gone through,” he says pragmatically. “I have to try. I’m not a scammer, I’m just doing what I have to to survive.”

I wonder if he ever worries about the legal implications of this set-up but he deflects. It’s the magazine that would end up being sued, after all, not him. He’s coy about how many publications he’s sent AI pitches to but he’s adamant that what he’s doing isn’t nefarious. He says that, had I commissioned the chicken shop article, he would have researched it online and written it as best he could. He claims to have relatives in London who could have visited the chicken shops. But the places he spoke about weren’t real, I say. The story wasn’t real. Wilson seems unperturbed. “I’m not a bad person,” he shrugs.

Wilson capturing a picture of himself in his Nairobi village using a drone

Wilson capturing a picture of himself in his Nairobi village using a drone

This sentiment is rather undercut by a link he sends me to a story that went live the morning we spoke, which is, by his own admission, “pure fiction”. It’s an essay called The Skip That Built a Family: How a Broken Led Zeppelin LP Taught Me to Love Imperfections, published on a website called I Have That On Vinyl. Byline: Joseph Wales. It’s an elegiac story about listening with his dad to a Led Zeppelin record that jumped at a certain point in the song, and how that jump became an integral part of the music for his family, leading to a lifelong obsession with damaged vinyl.

The story has some of the tell-tale signs of AI – em dashes, bullet pointed lists, words bolded up – but it also contains some quite beautiful turns of phrase. It describes a water-damaged copy of Pet Sounds where the warp slows Wouldn’t It Be Nice “just enough to make the teenage romance sound like a middle-aged memory”.

It describes how his “friend’s” Nashville basement studio “smelled of old electronics and cheap bourbon” and recalls the author dropping $200 on a pristine Mobile Fidelity Sound Lab reissue. In no possible world is this the work of a man with a solid but imperfect grasp of English who lives in the outskirts of Nairobi.

Domo arigato Mr. Roboto

Wilson and I end our call on good terms. He shares with me some Youtube videos he made eight years ago showing drone footage of his village, set to a hiphop soundtrack, and invites me to stay with him should I ever visit Nairobi. Still, I’m still not sure if anything he told me is true or if all of this has been a colossal waste of time.

But there is one more character in this story. When I was checking Joseph Wales’ references, I did get a reply, from Loud Interactive, an SEO agency in Chicago. “Hi, possibly a strange email but I’m a journalist in the UK and a guy called Joseph Wales has listed you on his resumé as an employer,” I wrote. “I don’t think he’s based in the US and I’m pretty sure the story he pitched to me was generated by AI – I wanted to check if he was indeed employed by you as an SEO copywriter… Hope you can help!” Within an hour I received a response – from the founder, no less.

Allow me to introduce you to Brent D Payne, a bull-headed gentleman who is not afraid to blow his own trumpet. His rather dizzying website is divided into subheaders that say things like “Brent D Payne is an SEO visionary”. There is a section dedicated to his “journey” from Oregon to California to Chicago. Even back in the days of web 1.0, Brent reckons he “had a vision for the future with the internet as he does now have vision of the future with AI”.

The personal website of Brent D Payne of Loud Interactive

The personal website of Brent D Payne of Loud Interactive

I enjoyed researching Brent. He likes to @ people like Elon Musk on X. His followers include Barack Obama as well as a couple of mutuals of mine. He was once mentioned in a New York Times story regarding a spat he was having with Google. He’s the kind of guy who is probably quite a big deal but thinks he’s a much, much bigger deal. The first line of his email to me – no “hello” – reads: “We had over 600 stay at home moms and dads working for us then. I fired them all and replaced them with [a] homegrown AI tool I built over the past two years. Managing AIs is much easier and more predicatable [sic] than humans.”

He then shared a link to a blog post from December 2024 about firing all those moms and dads, which he says was also written by AI. He signs off with: “I am not surprised someone we had employed may be trying to pass something off as original when it was AI generated. Lots of slimy writers out there. Not saying he is or isn’t one of them, but…”

I am a bit taken aback. Most founders are cautious when talking to journalists and very, very few respond when someone in another country contacts the generic email address at the bottom of their website.

I read his blog post and it is… quite something. “Yesterday morning, while making ‘roll-ups’ for my family, Mr. Roboto by Styx came on through our HomePods,” it begins. “You know that feeling when a song hits the right note emotionally and intellectually at just the right moment in life? There I was, with a crepe being served in one hand and a spatula in the other, singing ‘Domo arigato [“thanks a lot” in Japanese], Mr. Roboto…’ when a thought struck me: how fitting this song was for what we at Loud Interactive had just accomplished.”

Mr. Roboto, for those unversed in 1980s synth rock, is a song on Styx’s eleventh studio album Kilroy Was Here. It tells the story of a cyborg – neither man nor machine – finding his place in a world of humans, exploring themes of alienation and the need for connection. I do not think it is quite as pro-robot as Brent assumes. It goes:

You’re wondering who I am /

Machine or mannequin? /

With parts made in Japan /

I am the modern man /

…

The problem’s plain to see /

Too much technology /

Machines to save our lives /

Machines dehumanize

“The decision wasn’t simple,” Brent continues, “after all, we replaced 600 part-time, stay-at-home parents who had been with us for over a decade. But as I think about it in light of that Styx song, it feels like a necessary progression. It’s a moment where technology takes the baton from human hands… Domo arigato, Mr. Roboto echoed in my head as I worked on breakfast, handing out crepes and singing along.”

It’s quite an image: the tech founder in his fancy kitchen singing along to existential 80s dance-rock as a small army of moms and dads start glumly updating their CVs. It is also, if I may be so bold, a horribly written blog post. Perhaps he should have kept one or two of them around.

“Thanks for the reply,” I send back, “and fair enough – this isn’t an anti-AI story, more a story of how AI is changing the way people – and traditional media – works. As an editor these are questions I’m currently battling with, although I don’t like the idea of being entirely replaced by a consortium of LLMs! Did you ever regret casting off the 600 humans? Also is there any way of checking if Joseph Wales was among them?”

Brent, clearly having a quiet afternoon, replies immediately. “Zero regrets. Much better outputs from our tool.” He goes on to list all the things his proprietary AI can do before reassuring me that “Journalism is safe. Stay at home mom and dad’s [sic] that do spec writing… they’re obsolete. Joseph Wales fits in that category. Joseph worked for us. He wasn’t in our top 10% for output quantity or output quality. So, I never directly interfaced. But he did do a lot of spec writing for us and for a number of years. No clue if it was any good.”

So Joseph – or, more accurately, Wilson – did work for Brent. His resumé isn’t entirely fabricated. I’m inclined to believe he’s telling the truth about most of the other stuff he told me, too, although there’s no way to be sure.

A fatberg of hallucinated slop

As an editor, I clearly can’t condone using AI to generate made-up pitches, especially if you plan on sending them to me. The last thing we need is more people adding to the growing fatberg of hallucinated slop that, day-by-day, makes up a larger and larger proportion of the internet (some reports suggest up to 90 per cent of new online content could be AI-generated by 2026, although this statistic could itself be AI-generated for all I know).

But I do enjoy the irony that people put out of work by AI are turning to those same tools to re-enter the market through the back door, threatening to form a surreal feedback loop of garbled content, fragments of real life jumbled up and reassembled, a limitless supply of cut-and-shut cars rolling off the forecourt of an infinite number of dodgy garages.

The simple fact is, AI exists. It will change the face of almost every industry, upend and uproot us all, shake the system by its ankles with little regard for what might fall out of its pockets. And, as is the way of things, it will start at the bottom and work its way up. I don’t even think what Brent did is wrong, necessarily, although I could do without the triumphant tone and all the ‘Domo arigato, Mr. Roboto’ nonsense.

In light of all this, I can see why someone like Wilson might decide to finally take a leaf out of the book of those Nigerians he read about all those years ago. He’s smart, resourceful, charismatic and in danger of being utterly left behind, his livelihood swept away by a tsunami within which he couldn’t possibly stay afloat. There but for the grace of God go I, and you, and all of us.

Read more

Seraphine: Princess of Wales’ favourite owed a king’s ransom

Similarly tagged content:

Sections

Categories

People & Organisations