The Serbian summer has been marked by widespread anti-government protests and significant violence. Throughout August, police and pro-government activists have attacked demonstrators, some of whom fought back. Offices of the ruling party have been set alight, and Russia has promised undefined aid to the government of President Aleksandar Vučić.

But while Serbia has experienced the largest protests in its recent history, the European Union (EU) has merely expressed its “deep concern” amid the escalation of violence in which multiple protesters were injured and detained. This hesitation reflects Brussels’ concern that taking a tougher line could push Belgrade closer to Moscow and Beijing, while also jeopardizing access to Serbian raw materials at a time of escalating competition over critical resources.

The bloc is, however, missing the bigger picture. It only needs to reflect on other authoritarian crackdowns and draw obvious lessons.

The 2023-2025 protests in Georgia and the Russian-style government response have pushed a fundamentally pro-Western country off the path to European integration and onto the rocky road to enduring political repression.

While the EU eventually froze Georgia’s accession and provision of financial aid, the measures came too late and were too weak to alter the course of a determined authoritarian government.

The bloc seems set to make the same mistake again, but at a greater cost. Serbia shares a common border with the EU and has a significant ability to make mischief in its neighborhood.

It is time for a much more hawkish stance on Vučić’s administration and to hold his loyalists in government, parliament, and the judiciary accountable for their authoritarian policies. The EU should also consider suspending financial aid and preferential market access, as well as scaling up support for civil society and independent media.

The case is only underlined by the government’s continuing behavior. On August 27, the Organized Crime and Corruption Reporting Project (OCCRP) disclosed that Vučić allies had met the UK-based owners of the N1 TV channel to discuss the removal of its independent CEO. The government, its agencies, and a subsidiary of UK-based private equity firm BC Partners denied they were seeking to defang N1, which has given significant airtime to opposition demonstrations and corruption investigations.

This is a well-worn path. Hardline governments profoundly frightened by mass protests now have a plethora of policies and technologies available, many derived from Russia and other repressive states — leaked papers show, for example, that Serbia is secretly expanding its advanced Chinese surveillance systems from Huawei. The measures aim to stifle dissent, the work of activist groups, the free flow of information, and ultimately the stamina and financial resources of mass movements. Police violence and imprisonment are no longer the sole tools available to authoritarian administrations.

Left unchallenged, the EU risks losing a would-be ally in a continent increasingly divided between Kremlin-friendly and democratic, anti-authoritarian states. Serbia may become another Georgia.

Get the Latest

Sign up to receive regular emails and stay informed about CEPA’s work.

In order to impose direct costs without harming the Serbian population, the EU should use targeted sanctions (travel bans, asset freezes, and other tested measures) against enablers of the regime.

To avoid rapid deterioration in relations and simultaneously show its resolve, the EU needs to swiftly impose sanctions against mid-level officials in Serbia. The initial list may focus on senior security officers, who order violence against protestors, judges, who give harsh sentences to protestors, and issue lenient sentences to pro-regime figures.

However, if the regime doesn’t listen to its citizens and their demands for tough action against corruption while continuing to suppress protests, the EU should adopt more aggressive measures and impose sanctions against senior state officials.

The bloc holds considerable leverage. In 2023, it accounted for nearly 60% of the country’s trade. This influence is reinforced by the fact that the EU was the source of almost half of Serbia’s foreign direct investment (FDI) inflows in 2023 and provides billions of euros in grants from the EU budget, as well as loans.

One option is to review the association agreement between the EU and Serbia, which opened the EU market to Serbian goods. Since the agreement is based inter alia on democratic principles and human rights, the EU may threaten to suspend it if Belgrade doesn’t alter its approach. The bloc has more than enough reason to complain; Serbia’s track record in meeting the requirements for EU membership, a process now underway for 13 years, is somewhere between mediocre and poor.

The EU could also threaten to tighten investment screening and apply stricter scrutiny to FDI flows, particularly in regime-linked sectors.

However, the most immediate measure is to threaten to halt the disbursement of aid from various EU funds. For instance, if Serbia fails to improve its domestic repression, the EU may halt assistance coming from the €14.2bn ($16.5bn) Instrument for Pre-Accession Assistance, from which in 2024 it received €83.4m. In addition, Serbia is to be allocated €1.58bn by 2027 under the Western Balkans Growth Plan, which could also be suspended.

While increasing pressure on the government, the EU should at the same time strengthen Serbia’s civil society and independent media, who are the core drivers of democratic resilience. With rising tensions and calls for snap elections, the bloc could increase support for pro-democracy movements in Serbia such as NGOs, grassroots groups, election monitors, and student groups that lead the protests.

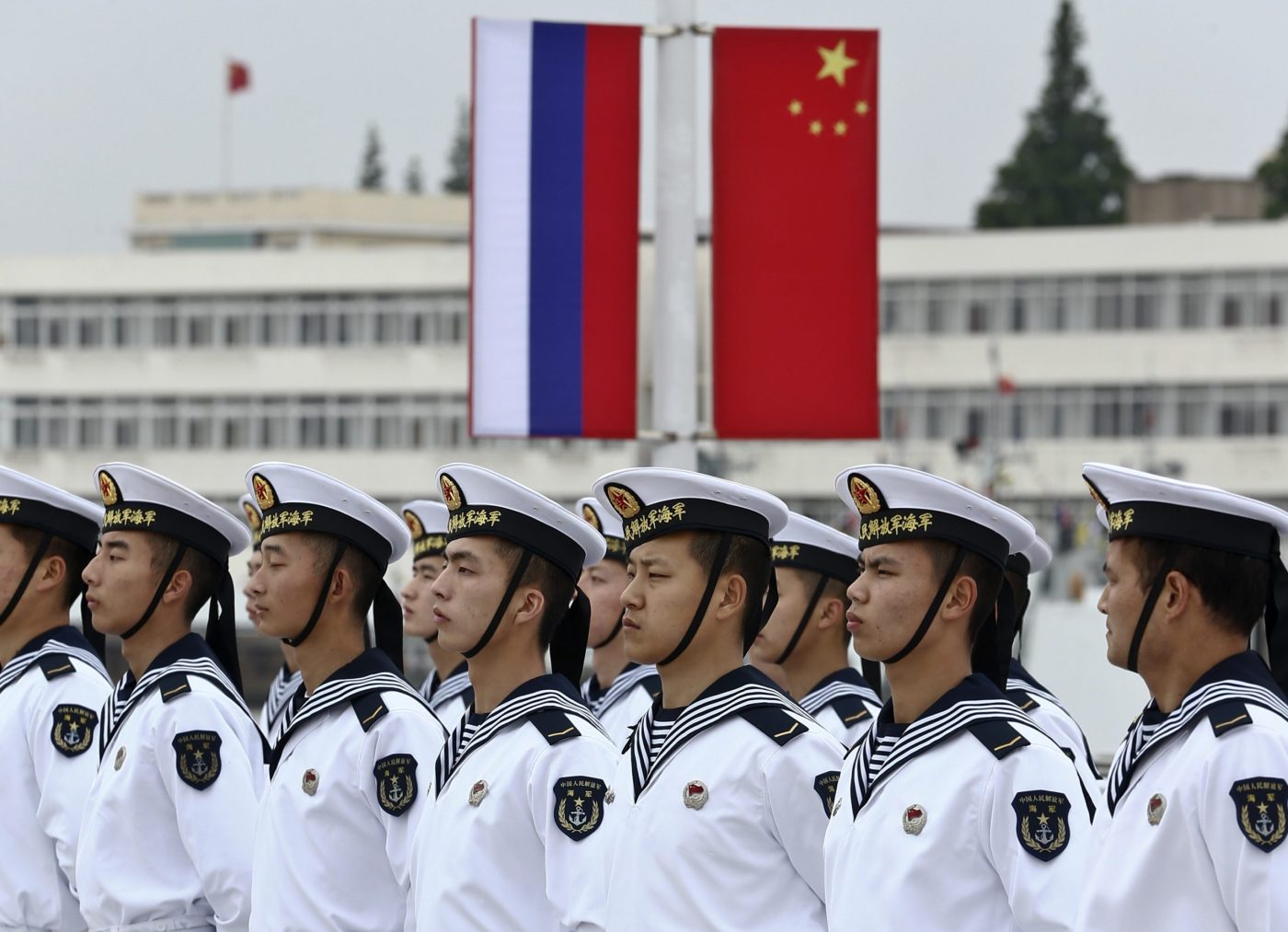

If it decides to remain silent, and thereby appease Vučić, the EU risks losing credibility as a protector of democratic values, and further undermine its appeal among young Serbs, who are already losing faith in the bloc. The greater risk is that Russia and China entrench in the Western Balkans as a corrupt and unpopular government is allowed to bully its way back into office.

Andrii Vdovychenko is an emerging expert in international security. He is currently pursuing an Advanced Master of Arts in European Interdisciplinary Studies at the College of Europe in Natolin and holds a Master’s in International Security and Development from Jagiellonian University. His research focuses on emerging technologies and strategic studies.

Europe’s Edge is CEPA’s online journal covering critical topics on the foreign policy docket across Europe and North America. All opinions expressed on Europe’s Edge are those of the author alone and may not represent those of the institutions they represent or the Center for European Policy Analysis. CEPA maintains a strict intellectual independence policy across all its projects and publications.

Europe’s Edge

CEPA’s online journal covering critical topics on the foreign policy docket across Europe and North America.