Arundhati Roy had never planned to write a memoir. That changed when she lost her most captivating and complicated subject: her mother, Mary Roy. Mother Mary Comes to Me is a window into Mary Roy’s world: a woman who built a school from scratch, fought for women’s equal rights under Christian inheritance laws, and navigated life in Kottayam like a superhero with the edge of a gangster till the age of 89.

Arundhati wanted to write about her mother without any resolution, leaving the loose ends flying. But it is also about what made Arundhati: hunger, cruelty, stigma, and generational violence, her mother’s bouts of asthma and violent rage. Arundhati left home at 18 to be on her own; and continue loving her mother. She slogged, worked, understood different loves, won a Booker prize, went to jail, still battles legal cases and shares her money to fund other people’s works.

In a world distraught by so much emotional, physical, social violence, this book is a stunning, honest reminder that we are all broken but capable of love, anger, horrible things, and extreme generosity. As Arundhati says: “Because people are not ideologies, they are wild. Some cannot be put under neat divisions, categories, or ‘faux-therapy’ labels, and yet need to be part of literature and history.” Excerpts from an interview:

In a world, where is a term for everything and everyone, where only pure revolutionaries are accepted, how important is it to write about your mother, Mary Roy?

Because people are pretty wild, everybody is rushing to judgment now. When I was writing this book, I had many moments when I felt that I was a little ashamed of my own sorrow. When she passed, she was 89, I’m in my 60s. I thought why?

And to understand the fact that just to manage somebody in your life, you had to become a peculiar shape, and now that shape doesn’t make sense. For example, you could be so progressive and so assertive in some ways, and then suddenly, you can turn around with some completely casteist ideas, and all these things — how do you hold them together? But that is what people are. They are like little pieces of disparate things held together by their muscles and blood.

What does it take to accept our parents as they are?

I told somebody the other day that I think the truth is that I was her mother. I was the one that was indulging this wild, genius, cruel, mean, wonder child. I was the one who had to hold my peace because of her illness all the time. In many ways, our roles were completely reversed. I felt that ultimately, we were just two adults who were sort of dealing with each other in some way. I stopped being a child or having any expectations of her as a mother long ago. I left. Because I would have been crushed if I hadn’t…But I never wanted to defeat her. I never wanted to win. I wanted her to go out, like a queen. And she did.

You do that for your father as well, you let him be when you met him for the first time.

As I write in the book, I did spend a whole night away looking at myself, wondering, God, what am I going to need, and then it was just like beyond everything I could have possibly imagined. I was 25. I was already a pretty political being. It took me three seconds to shift between shock at seeing him in the complete mess that he was — peeing in his clothes, his ear bitten off and all that. And then suddenly being like, ‘Oh, God, thank God he’s not a CEO!’ I would have been more distressed dealing with that.

It’s not only that my mother experienced the violence of her father, but she also inherited that violence. It wasn’t just a reaction to that violence. She was also like that. I can see how both my brother and I made a very conscious effort not to replicate that. But I think intergenerational violence and trauma are very real things. Not just intra-family, but also caste, ethnicity and religion and all of that.

You can feel it trapped in your muscles sometimes. I feel that if there has been violence, and you have been the victim of it , emotional or physical or sexual or social, you have to find the strength to not think of yourself as a victim. The minute you do that, you circumscribe yourself. That’s not easy to do in our social systems. That’s not easy to do in today’s India, [if you are] a Muslim, woman, whatever, but even if it’s not easy to do, it is the task that you have. No one else can sort you out.

You have a towering personality. Who would have thought that you also had your struggles of coming from a small town and being in this big city?

For me, the guiding principle has been the search for real liberty, real freedom. Obviously, freedom from whatever was going on at home. People say, “you were so brave.” I say, “no, I wasn’t brave. I did not have a choice. My choice was to be crushed and killed.” So it’s not bravery, it’s desperation. But once you make that choice then the point is why? Because I want to be happy, not because I want to suffer…

It’s been a constant search for some sort of ideal freedom in your head. I’m following some sort of chemical trail in my head, which is the trail of freedom. That means freedom from being trapped by your attachment, from having a lot of money or wanting to be famous forever, or indeed wanting to look young forever or wanting to Botox my way into youth. I don’t want to. I just want to be, just let me be.

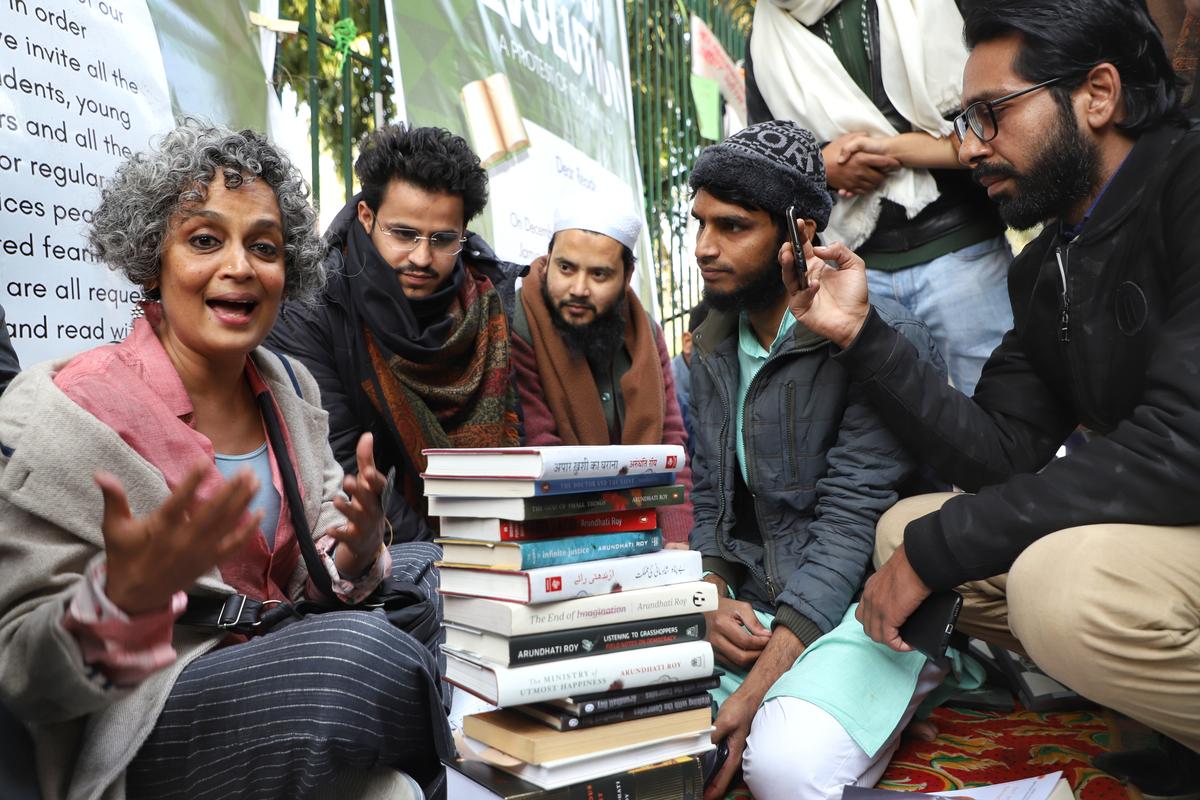

Arundhati Roy at Jamia Millia Islamia to show solidarity with students during an anti-CAA protest in New Delhi, India, on January 11, 2020.

| Photo Credit:

Getty Images

You mention a number of times that you ‘make your safest place the most dangerous, when it is not, I make it so.’

Once childhood has been totally unsafe… I mean, it can be that you live in Kashmir or you live on the streets, and you have external dangers. But it’s a different matter if your own mother is the danger. Then you don’t trust anything. I’m always drawn towards the unsafe. It’s easy for me to understand that. It’s harder for me to understand this happy family s**t. So sometimes, even when there is a relationship which seems very secure, it makes me almost feel like I can’t breathe. Like, “where’s the danger? Let me go!”

In this context, how do we understand love? Not just from people, but like those you mention in the book — squirrels, dogs, the tree outside your window.

I think that is a choice that one makes. There’s a conventional love, which is just like maa-baap (mother, father), or beta (son), or baccha (child). Then if that’s not something that you’ve chosen or that’s not something on offer for you, then are you going to get bitter? Or are you going to just find a whole spectrum of things outside of that, of friendships, of nature, of the world, which becomes a very intimate thing. So for me, it is like the political stuff that I write about. Or this book that is written in the backdrop of what’s going on in Gaza. For me, that is as personal as anything else. And especially to women, I don’t have any lectures — ‘don’t do this’; ‘don’t get married’. No. But there’s so much else also to choose from. There are so many other ways in which you can live your life. Apart from these standard little kind of roadmaps that are given to you.

You mention in the book how after you won the Booker Prize, people started talking about The God of Small Things in other ways and deracinating it of its politics. Is there a machinery at work that wants to remove politics or ground reality from literature?

I think there definitely is; that doesn’t mean it works, but there is definitely that effort.

At some point, maybe up to five or six years ago, there was a sense that literature is something else, and politics is something else. I think now things have changed because the world has moved into some other space. We cannot deny that there was a whole industry of writers who thought that literature and politics are two separate things, and who did not see that even if you think you’re writing something which isn’t political, your politics shines through it.

When I wrote The God of Small Things, I suddenly became this celebrity on the cover of every magazine. Then there was this rage when I wrote The End of Imagination, and then I started writing on Narmada.

You do have to go through a period where people misunderstand you, call you names, attribute motives to you and all of that. I think my Mary Roy training of not responding helped me there. I was like, I’ll just keep doing what I’m doing until they get bored, or tired, or realise that at least they aren’t true.

What’s very interesting is that while writing those essays, I knew that I was going to get a hate attack. I wasn’t necessarily writing to be liked. The like button didn’t exist. I wonder where that is anymore, because now, even if you’re in the alternate media, you have to be liked. You have to belong somewhere. Whereas at that time, I belonged nowhere. I was just saying what I thought.

Now, it is very temporary, but there’s a level of democratisation because of online. But it’s still a corporate space, still controlled. You move everybody online and then you shut off the internet. For months, like they did in Kashmir. It’s like you’re forcing everyone economically in terms of media, everything online, and then you control it. So the minute things are not to your liking, you switch it off, and here we are, all of us thinking they’re free and so on.

Arundhati Roy slogged, worked, understood different loves, won a Booker prize, went to jail, still battles legal cases and shares her money to fund other people’s works.

| Photo Credit:

Getty Images

In the book, you write of wanting to think alone. How does one think alone in the time of social media?

I would say switching off for at least some days week. I have nothing against social media. I have nothing against Facebook, or whatever, forgetting the politics of Mark Zuckerberg. The reason I’m not on social media is not a moral judgement. It is that fear that your head will just be full of noise and there’ll never be that time to contemplate, even if you’re alone, because you’re never alone.

As it is obvious in my book, I grew up near a river, with squirrels and no shops and no restaurants and no theatre and no phone.

And that’s fundamental to my makeup, and it’s a privilege. People, are growing up suckling on mobile phones, even before their brains are formed. Other people are pouring more information than any human brain can possibly process.

So I feel like we are heading toward a mass mental health crisis. Earlier, they used to say that psychosis had to do with hearing voices in your head. Now, you can never be alone. All the time there are just these voices.

I wrote an essay once, ‘Capitalism: The Ghost Story’ – how charities, and these are ways of corporates gaining more traction, are actually influencing or owning the process of policy-making itself. So one developed a pretty solid critique and a hostility towards these corporate entities. You knew that they were up to turning rights into charity, turning activists into employees, all of that was going on.

When my books began to earn more money than I needed, the first thing is that people are unable to say that I don’t need this much. I’m happy. I’m not sacrificing. I’m wearing all the clothes I want, I’m having all the fun I want, but why not share it?

Arundhati Roy in a cafe in New Delhi.

| Photo Credit:

Getty Image

Now that’s a delicate process of how to do that. How do you make it clear that it’s a political act of solidarity, not charity. It’s not some guilt trip.

It is not my baap ka paisa (father’s money). It’s what I have earned with my work. It is just the same thing as feeling that the political is personal and vice versa.

So we set up this Trust with people who I love and who I agree with politically.

The whole point of it was that we would not be throwing money at people. We would help if someone was already doing something, and needed a little push. You wouldn’t give money for someone to start doing something. They should have already been doing that thing.

Secondly, there are so many people who don’t know how to work this NGO machine and make proposals and write in English. There are so many people, so many wonderful people who are working, who just need that little bit of help, of transport, or just to survive.

It’s not something you are doing for yourself. It’s public money, but it has to be used responsibly. And I feel like people — writers and all — nobody writes about money.

Arundhati Roy at the 2019 Hay Festival in Hay-on-Wye, Wales.

| Photo Credit:

Getty Images

You write about this alloy created by blending Hindu nationalism and corporate interests. In the last 11-12 years, how has it shaped not just India but the world around us?

In The Doctor and the Saint, I wrote, if you just look at who these corporations and what castes these families belong to…what does it show?

It’s not just Hindu nationalism. It’s like modernising and corporatising caste in that way. It’s absolutely shocking. Then you look at the judges, you look at the media, the ownership, it’s like you’re running an apartheid society, but it’s not colour coded, it’s got some other kind of code. What is the aim of this? The aim of this is that those particular castes continue to rule disguised as nationalists. And that wealth continues to be concentrated in fewer and fewer hands.

Recently your book, Azadi, was banned in Kashmir. You have had UAPA cases, you’ve been to jail. But you write in the book, “The more I was hounded as an anti-national, the surer I was that India was the place I loved, the place to which I belonged.” Why?

A lot of people who live in the West would ask me in the slightly patronising way, “why don’t you leave? Or do you think of leaving?” Now, what is that question? What would I do there? Live like a mouse, keep quiet, not do anything?

At least here, you’re fighting for something that you love. There is much that one loves about this place. So that’s what fuels the anger. It’s not that you’re indifferent to it. And we all remember, but in better times, the meaning of dignity, which is missing now. It’s missing socially, politically. It is embarrassing the way people strut around, and about nothing. I have no national pride. Unless someone can tell me what I should be proud about. I have a lot of love, but no national pride.

Mother Mary Comes to Me

Arundhati RoyHamish Hamilton₹899

The Delhi-based independent journalist is the author of ‘The Many Lives of Syeda X.’