Stanley Kubrick’s Eyes Wide Shut (1999) spends over two and a half hours roaming the streets of Manhattan—except not a single frame was shot there.

The movie’s New York is a phantom city, conjured entirely in London through obsessive set building, camera trickery, and a level of production detail that borders on obsessive compulsion. Watching it, you might swear you’ve seen Greenwich Village at midnight. In reality, you’re looking at Pinewood Studios under Christmas lights.

Kubrick had no interest in a quick trip to the U.S. He famously hated flying and refused to leave England for decades, yet he wanted Eyes Wide Shut to feel grounded in the specific rhythm, geography, and visual density of New York.

That paradox—needing an authentic Manhattan but refusing to film there—shaped one of the most fascinating acts of cinematic sleight of hand in modern filmmaking.

On the surface, this is a story about location doubling, but in truth, it’s about how production design, editing, sound, and performance can work together to sustain an illusion so completely that audiences never think to question it.

Let’s walk through how Kubrick built New York without ever setting foot in it.

Why London?

Kubrick’s reluctance to leave England wasn’t a secret. After settling there in the early 1960s, he avoided air travel entirely, partly due to safety concerns and partly because he preferred working close to home. That preference shaped films like Barry Lyndon (1975) and The Shining (1980), both of which were shot entirely in the UK despite their foreign settings.

With Eyes Wide Shut, the problem was trickier. This was a film about Dr. Bill Harford (Tom Cruise), a wealthy Manhattan doctor who slips into a hidden world of desire and danger after his wife Alice (Nicole Kidman) confesses a sexual fantasy.

The city is so much more than just a backdrop—it’s a character. To make it work, the production had to reconstruct enough of New York’s visual language that viewers wouldn’t notice they were watching a British imitation.

And the challenge wasn’t only physical. New York has a unique cultural atmosphere: the density of storefronts, the width of the sidewalks, the placement of streetlamps, ambulance sirens, the way the traffic flows. Kubrick and his team had to replicate those textures without leaning on the crutch of actual city footage.

Building a Phantom City: Set Design & Art DirectionThe Streets of “Manhattan”

Pinewood Studios’ backlots became the skeletal frame for Kubrick’s New York. Production designer Les Tomkins and art director Roy Walker studied Manhattan’s street grid and architecture in microscopic detail, reconstructing blocks that could be redressed to look like different neighborhoods.

London locations doubled in clever ways. Hatton Garden was used to show streets in Greenwich Village. The Pinewood Studio set was created with altered façades and shop signs to match the storefront typography of Greenwich Village. Fake taxi stands and phone booths were installed to anchor the illusion. In some cases, the same stretch of street was filmed from different angles to serve as entirely separate locations.

The Sonata Café & Other Key Sets

One of the film’s most memorable sets, the Sonata Café, was a hybrid of New York jazz club aesthetics and European café design. It was entirely built on a soundstage, with walls dressed in warm neon glow and a layout that felt naturally cramped.

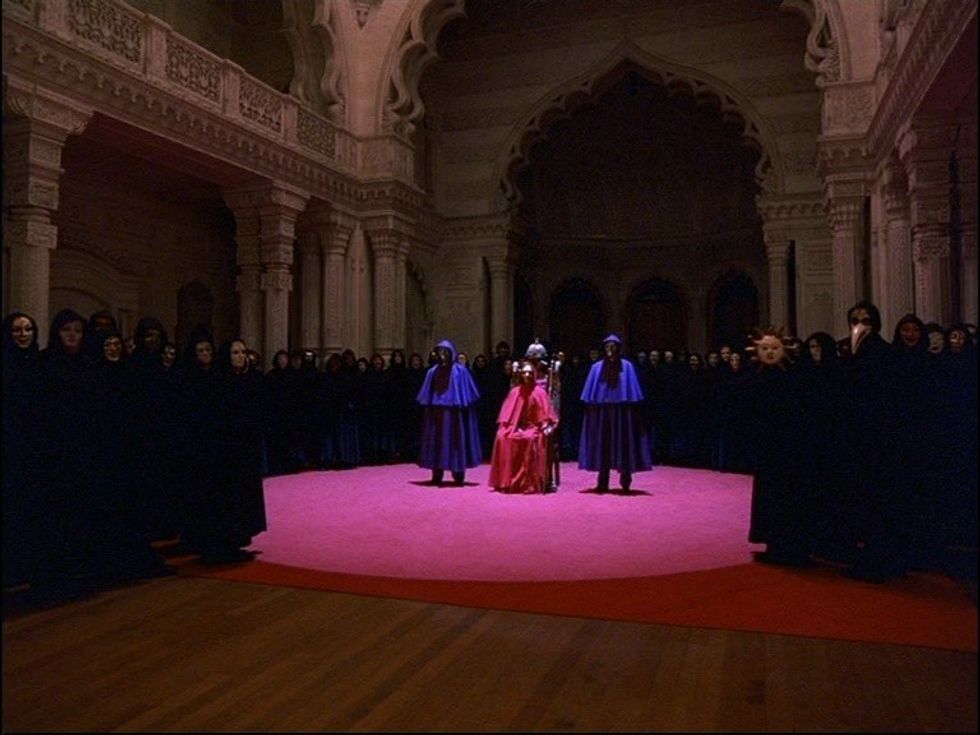

The infamous masked-ball mansion—a turning point in the film—was actually a British country estate. Its interiors were redecorated to resemble an opulent Long Island manor, complete with faux marble floors and imposing staircases. The shift from urban streets to this secluded, ritualistic space felt seamless because both environments were controlled down to the millimeter.

Visual Tricks: Editing, Lighting, and Forced PerspectiveThe Power of Editing

Kubrick’s editing choices masked the absence of New York establishing shots. He avoided wide aerial views of the city, instead keeping scenes tightly framed so that street backgrounds offered just enough detail without inviting scrutiny. This made the streets feel intimate, almost claustrophobic, aligning with the film’s dreamlike paranoia.

Lighting & Atmosphere

The perpetual presence of Christmas lights was more than seasonal dressing—it was a visual strategy. They added depth, color contrast, and a festive yet unsettling mood that helped disguise artificiality. Kubrick also leaned on fog machines and diffusion filters to blur background details, making it harder for audiences to clock the sets as soundstage builds.

These atmospheric touches gave Eyes Wide Shut a visual texture that felt less like a documentary portrait of New York and more like a half-remembered vision of it.

The Sound of New York: Audio Illusions

Kubrick sidestepped the obvious cues. Instead of filling the soundtrack with honking horns, shouting pedestrians, and subway rumble, he kept the city’s sonic identity muted. The ambient noise felt subdued, even in outdoor scenes, which subtly shifted the film into a surreal register.

This choice also left room for Jocelyn Pook’s haunting score to dominate, threading an eerie, almost ceremonial quality through the city sequences. The result: a New York that felt both real and unsettlingly removed from reality.

The Role of Special Effects & Matte Paintings

Digital effects were used sparingly. Some exterior skyline shots used digital composites and matte paintings to suggest New York’s architecture, but Kubrick preferred physical builds over CGI.

The choice wasn’t about budget—it was about control. Practical sets allowed him to dictate every shadow, every beam of light, every inch of visible architecture. Even the skyline shots were designed to be glanced at, not studied, reinforcing the dreamlike tone.

The Performances: Acting in a Fake New York

For Tom Cruise and Nicole Kidman, the New York setting existed mostly in their imaginations. Kubrick directed them with a focus on intimacy and body language, keeping close-ups dominant. That proximity meant the audience spent more time watching faces than scanning the environment for authenticity breaks.

By anchoring the emotional core in the performances, Kubrick made the setting almost secondary in the viewer’s perception—an essential trick when your “Manhattan” is 3,000 miles off target.

Reception & Legacy: Did the Illusion Work?

When Eyes Wide Shut premiered, few critics mentioned the fake New York—proof that the illusion held. For some, the slightly unreal quality actually enhanced the film’s themes, mirroring the blurred boundary between Bill’s waking life and the secret world he stumbles into.

In the years since, other films have borrowed this approach. The Batman (2022) turned Liverpool into Gotham, and productions like V for Vendetta (2005) transformed London streets into entirely different cities. Kubrick’s example proved that a location’s “truth” is often a matter of perception, not geography.

Kubrick’s Masterful Deception

Stanley Kubrick built a New York that never existed, and yet it’s one of the most distinctive screen versions of the city. Through carefully constructed sets, atmospheric lighting, restrained editing, and performances rooted in intimacy, he replaced geographic truth with cinematic truth.

The irony is that the artificiality makes Eyes Wide Shut more thematically potent. The city, like the film’s masked rituals, is an elaborate façade—convincing enough to pass, yet deliberately detached from reality. In the end, Kubrick, by recreating Manhattan, made a version of it that exists only in the realm of dreams, forever sealed in the film’s strange, hypnotic world.