HOW TO LIVE with the giant on its doorstep is always a conundrum for post-Brexit Britain. Since Brexit took effect in January 2021, goods exports to the EU have fallen sharply because of new non-tariff barriers. One way to avoid these would be closer alignment with EU rules, as was proposed for food and energy in the deal that Sir Keir Starmer struck with EU leaders in May. This week Nick Thomas-Symonds, minister for EU relations, stoutly defended this deal against Nigel Farage’s attacks, arguing that his promise to reverse it would cost the economy £9bn ($12bn) and raise food prices.

PREMIUM Britain’s Prime Minister Keir Starmer (AFP)

PREMIUM Britain’s Prime Minister Keir Starmer (AFP)  Chart

Chart

How far could alignment go? One case study is the chemicals industry. Last year Rachel Reeves, now chancellor, said nobody had voted to leave the EU because chemical regulations were all the same. This raised hopes that the industry might be included in the deal in May, but it was not. Yet the chemicals business matters. Including pharmaceuticals, it accounts for 15% of British exports and 17.5% of R&D. Over 60% of its exports go to the EU. And it is suffering. Steve Elliott of the Chemical Industry Association says total output volume is down by 35-40% since January 2021.

Like food, the chemicals industry is heavily regulated. Because Britain left the EU’s single market, it also left its REACH system of chemical regulation, based on the European Chemicals Agency (ECHA) in Helsinki. A half-hearted effort to stay in was dismissed by Brussels as a bid to cherry-pick bits of the market that the British liked. So Boris Johnson’s government set up UK REACH. Yet so far this employs just 40 staff, against almost 600 at the ECHA. And its budget of £10m a year is a tenth of what the EU spends in Helsinki.

UK REACH has accordingly been repeatedly delayed. Last month the government proposed to push back the initial deadline for firms to register yet again, to 2029. And regulatory divergence may be growing. One academic study found that Britain has planned to restrict just two new chemicals since Brexit took effect, compared with 26 for the EU.

For the industry the cost of joining UK REACH is prohibitive. Richard Ward, boss of the Airedale chemicals company in Keighley, points out that companies need to seek approval for more than 22,000 chemicals. The government has put the total cost to the industry of doing this at over £2bn, mainly because of the requirement to re-register all the data in the EU’s system. Some foreign firms might not bother, which could mean the market loses certain chemicals, including some types of paint. Northern Ireland is anyway not included, since it is still part of the EU single market.

Is there an alternative? Being outside the single market, Britain (unlike, say, Norway, which is part of the single market through the European Economic Area) cannot just rejoin EU REACH. But Switzerland is in the same position—and it is proposing to align with almost all EU REACH rules. It will not require any chemical that is authorised by the EU to re-register at home, saving the industry a lot of hassle.

Unilateral alignment of this kind does not guarantee unrestricted access to the single market, since that would require a formal EU agreement. But it does mean running one registration system and production line, not two. Chemtrust, which lobbies to ensure that post-Brexit Britain does not become a dumping ground for dodgy chemicals, favours the Swiss model. Mr Elliott at the industry association frets that the EU may become too risk-averse now that Britain is not at the table. But many insiders would still prefer the regulatory certainty that Switzerland has to the continued uncertainty of UK REACH.

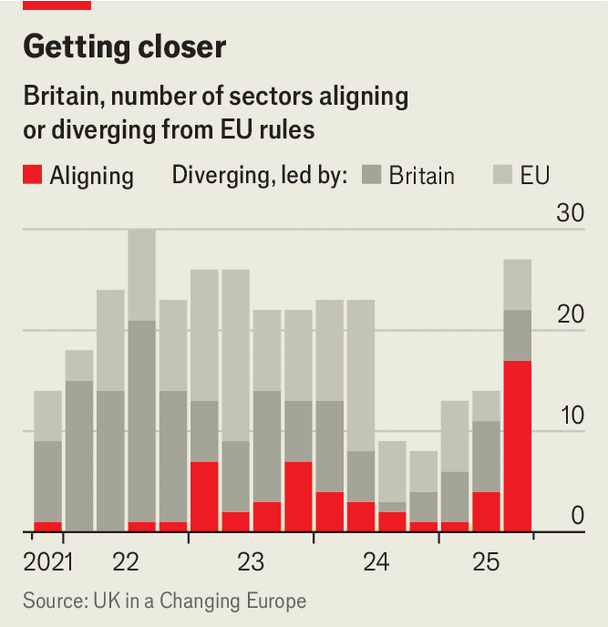

Closer alignment with EU rules, as opposed to divergence, is now a broader trend. The UK in a Changing Europe, a think-tank, has been tracking it since January 2021, and it finds a sharp increase over the past six months in the number of sectors where the rules are becoming aligned (see chart). Sometimes, as with the agreement on food, this is well publicised. But often it has been surreptitious. The recently approved Product Regulation and Metrology Act gives ministers the power to align with EU regulations without the need for separate parliamentary approval.

Why the surreptitiousness? One answer is the opinion polls, especially the strong support for Mr Farage’s Reform UK . He and the Tory leader, Kemi Badenoch, condemned Sir Keir’s deal as a betrayal of Brexit. Yet both have since made less noise about it. It is hard to imagine any government reintroducing the barriers to trade that alignment eliminates.

The EU has also become more accommodating. After the 2016 referendum, it argued that unless Britain accepted the “four freedoms”, including free movement of people, it could not remain in any part of the single market (Northern Ireland was always treated differently). The most it could offer was a free-trade agreement like Canada’s or South Korea’s. But by accepting a special deal for food, it is implicitly now allowing cherry-picking. It could easily extend this to chemicals, as it is doing for Switzerland. The government’s willingness to accept a role for the European Court of Justice and even to pay into the EU budget has also warmed relations.

Brexiteers often argue that the whole purpose of leaving the EU was to diverge from its costly regulations. Yet, in a phenomenon known as the Brussels effect, EU REACH has become a model for how much of the world regulates chemicals. Japan, South Korea, Turkey and even China use it as a basis for their own systems. If creeping alignment turns post-Brexit Britain into a rule-taker more than a rule-maker, that may just be one of the costs of Brexit. Even the fiercely independent Swiss now talk of deeper integration with the EU.

For more expert analysis of the biggest stories inBritain,sign upto Blighty, our weekly subscriber-only newsletter.