Recently I’ve spent a lot of time listening to the radio. It’s been a companion as I move house, burbling away happily in the background as I wait for a delivery or struggle with the mass of cardboard that builds up in the corner of the room once furniture has been assembled.

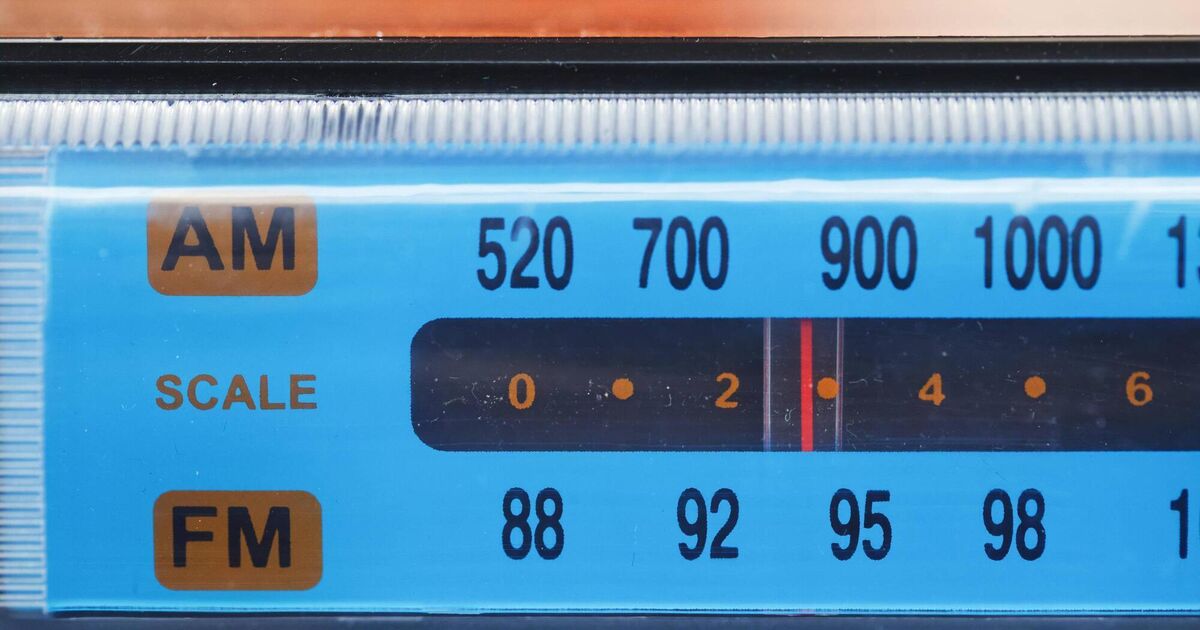

I bought a new radio specifically for this purpose: An AM/FM radio that’s largely unremarkable. It’s analogue in the extreme. It hasn’t heard of Bluetooth and, frankly, doesn’t want to know about it.

Karl Whitney: ‘Radio, as I’ve pointed out, thrives on small talk, and if you’re too tense it’s unlikely that you’ll take the opportunity to communicate with people in a warm and engaging way.’

Karl Whitney: ‘Radio, as I’ve pointed out, thrives on small talk, and if you’re too tense it’s unlikely that you’ll take the opportunity to communicate with people in a warm and engaging way.’

When I published my first book, I ended up being interviewed on radio stations, answering questions that I hadn’t really thought about and that only had a tangential relationship to the book that I had written.

In the late ’80s, there was a community radio station near my primary school, at the top of the Greenhills Rd in Tallaght village in Dublin, where my mam presented a programme a few times a week.

The studios were in a terraced cottage that had a huge mast on top — quite incongruous, but that added to the charm.

There were, I think, two rooms inside, the main one being the studio itself. It was rudimentary: There were some shelves holding vinyl records and a desk from which sprouted a microphone.