Jongelui bouwen huttendorp in Amsterdam Noord (“Youth building a hut village in Amsterdam North”), 1960s. Image © Harry Pot via Wikimedia Commons, public domain

Jongelui bouwen huttendorp in Amsterdam Noord (“Youth building a hut village in Amsterdam North”), 1960s. Image © Harry Pot via Wikimedia Commons, public domain

Share

Share

Or

https://www.archdaily.com/1033445/unconventional-playgrounds-built-from-junk-shaped-by-concrete-freed-by-play

What if the best kind of play isn’t the safest? For decades, cities have built playgrounds to be clean, colorful, and easy to supervise. Yet these spaces—designed more for adult peace of mind than for children’s curiosity—often strip away what makes play truly transformative: risk, unpredictability, and self-direction. Rising safety standards, shrinking public space, and the commercialization of play equipment have only further narrowed the possibilities for children’s independent exploration. From a junkyard in 1940s Copenhagen to the concrete landscapes of postwar Amsterdam, a handful of architects, planners, and activists have challenged the idea that play must be neat and controlled. Their unconventional playgrounds—made of loose parts, raw materials, and abstract forms—gave children the freedom to build, demolish, explore, and get dirty.

Copenhagen, 1943 — Play in the Shadow of War

In a residential neighborhood in Emdrup, landscape architect Carl Theodor Sørensen turned a vacant lot into what became known as a “junk playground.” Instead of swings and slides, children found loose materials like wood, ropes, tires, and sticks. Sørensen had already observed that children often ignored his carefully designed play equipment in favor of improvised materials—objects they could use and transform themselves.

Related Article Playscapes and Public Imagination: The Ambiguous Play in Urban Life of Hong Kong

His experiment emerged in the wartime context of scarcity, when metal and manufactured equipment were hard to come by, but also in a moment when European planners were beginning to talk about children’s needs while re-building cities. The Emdrup site suggested that limited resources could be a strength, fostering a form of play that was creative, hands-on, and collaborative.

Jongensdorp, a children’s village in Amsterdam-Noord, Netherlands, 1960. Image © Wim van Rossem via Wikipedia, under license CC0

Jongensdorp, a children’s village in Amsterdam-Noord, Netherlands, 1960. Image © Wim van Rossem via Wikipedia, under license CC0 Jongensdorp (“boys’ village”) in Amsterdam Noord, 1960s. Image © Harry Pot via Wikimedia Commons, public domain

Jongensdorp (“boys’ village”) in Amsterdam Noord, 1960s. Image © Harry Pot via Wikimedia Commons, public domain

This model was groundbreaking because it offered no fixed structures, only the possibility to build, demolish, and rebuild. The playground was not a finished product—it was an open process.

Lady Allen — Planning for Play

A few years later, British landscape designer and activist Lady Allen of Hurtwood visited Emdrup and began championing the idea in the UK. She argued that conventional playgrounds were tidy, over-managed, and unchallenging for children. Drawing from her background in social reform, she positioned adventurous play as essential for developing resilience, cooperation, and problem-solving skills.

Her advocacy resonated with emerging theories in developmental psychology from figures like Jean Piaget and Maria Montessori, who emphasized the importance of self-directed, hands-on learning. Lady Allen maintained that the small physical risks of adventurous play were far outweighed by its long-term benefits to children’s confidence and emotional health. Her campaigns reframed play as a fundamental right, not a decorative amenity, and pushed against designs that prioritized adult control over children’s self-expression.

Amsterdam — Mulder and Van Eyck’s City of Play

Meanwhile, in postwar Netherlands, urban planner Jakoba Mulder promoted the creation of micro-playgrounds in vacant lots, sidewalks, and small gaps throughout Amsterdam. Her vision was clear: any resident could propose that a disused urban space be turned into a children’s play area. Inspired by the value of unstructured play, Mulder favored minimal design interventions that gave children full authorship over how they used the space. It was an urban policy on a child scale.

Working alongside Mulder, architect Aldo van Eyck translated this vision into a distinctive architectural language. Between 1947 and 1978, he designed hundreds of playgrounds across the city, turning empty plots, street corners, and leftover spaces into interconnected micro-worlds. His vocabulary of simple geometric forms—low climbing domes, stepping stones, sandpits—was deliberately abstract, inviting multiple interpretations.

Van Eyck designed hundreds of site-specific playgrounds across Amsterdam between 1947 and 1978, creating a connected network of play woven into the city’s streetscape. He deliberately eschewed fences, allowing the spaces to blend into their surroundings and enabling children to move fluidly between play and daily urban life. Many of these playgrounds were installed in vacant postwar lots, transforming bomb-damaged or neglected spaces into vibrant social nodes. In doing so, Van Eyck’s work became an act of urban recovery, where children’s play was not just accommodated but placed at the heart of rebuilding community life.

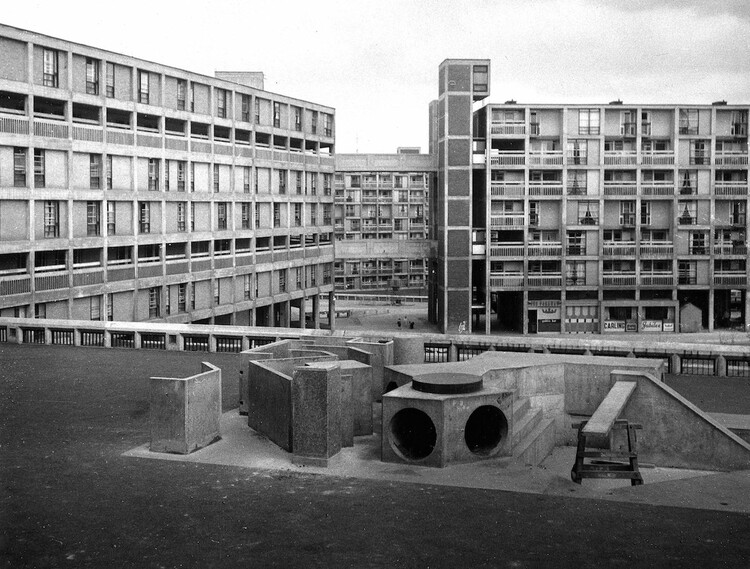

Brutalist Playgrounds — Rough Concrete, Boundless Play

In the 1950s and 60s in the UK, a series of playgrounds emerged that used concrete, massive abstract forms, and bold architectural gestures—designs that decades later would be reinterpreted in the 2015 exhibition The Brutalist Playground by Assemble and Simon Terrill.

These structures, often part of social housing estates, resembled ruins or bombed-out cityscapes. Yet children embraced them: their warmth in the sun, the echo of footsteps in hollow cavities, the tactile grip of rough surfaces. They became arenas for climbing, hiding, and inventing rules—a form of unscripted play that was physical, social, and deeply tied to the imagination.

© Park Hill Estate, Sheffield – 1962. Image © Arch Press Archive RIBA Library Photographs CollectionContemporary Adventure Playgrounds — Risk in a Regulated Age

© Park Hill Estate, Sheffield – 1962. Image © Arch Press Archive RIBA Library Photographs CollectionContemporary Adventure Playgrounds — Risk in a Regulated Age

Adult presence, even with good intentions, can sometimes limit authentic play. That’s why many contemporary adventure playgrounds restrict parental involvement. In some cases, parents sign a waiver and leave children in the care of trained playworkers whose role is to support, not direct, activity.

This model, found in countries like Japan, Germany, the UK, and the US, persists despite modern legal and insurance pressures. In many cities, liability concerns and standardized safety codes have all but eliminated such spaces. Those that survive often rely on strong community advocacy and creative navigation of regulations.

Contemporary examples include Kolle 37 (Berlin), Hanegi Playpark (Tokyo), The Yard (New York), and Land at Plas Madoc (Wales). Each of these offers children space to make decisions, take risks, get dirty, and fail—experiences increasingly rare in urban childhoods.

Why This Matters Now

In an era where playgrounds are increasingly hygienic, colorful, certified, and adult-monitored, perhaps we should ask: what have we lost? What gets left behind when we prioritize safety over exploration, cleanliness over creativity, and order over spontaneity?

The right to play is not just the right to enter a designated area. It might instead be the right to risk, uncertainty, mess, and unfinishedness. The history of unconventional playgrounds shows that freedom in design can emerge from scarcity, social reform, and a willingness to see the city through a child’s eyes.

This article is part of the ArchDaily Topics: Shaping Spaces for Children, proudly presented by KOMPAN.

At KOMPAN, we believe that shaping spaces for children is a shared responsibility with lasting impact. By sponsoring this topic, we champion child-centered design rooted in research, play, and participation—creating inclusive, inspiring environments that support physical activity, well-being, and imagination, and help every child thrive in a changing world.

Every month we explore a topic in-depth through articles, interviews, news, and architecture projects. We invite you to learn more about our ArchDaily Topics. And, as always, at ArchDaily we welcome the contributions of our readers; if you want to submit an article or project, contact us.

Related Article Playscapes and Public Imagination: The Ambiguous Play in Urban Life of Hong Kong

Adventure playground, Copenhagen, 1985. Image © Mogens Falk‑Sørensen, Stadsarkivets fotografiske Atelier via Wikimedia Commons, under license CC BY 2.5

Adventure playground, Copenhagen, 1985. Image © Mogens Falk‑Sørensen, Stadsarkivets fotografiske Atelier via Wikimedia Commons, under license CC BY 2.5 Band-ship (“bandenschip”) structure made of tires in Oostenburgermiddenstraat, Amsterdam. Image © Anefo via Wikimedia Commons, under license CC BY-SA 3.0

Band-ship (“bandenschip”) structure made of tires in Oostenburgermiddenstraat, Amsterdam. Image © Anefo via Wikimedia Commons, under license CC BY-SA 3.0 Miniature city built by children in Amsterdam, 1950s. Image © Harry Pot via Wikimedia Commons, public domain

Miniature city built by children in Amsterdam, 1950s. Image © Harry Pot via Wikimedia Commons, public domain Park Hill, Sheffield. Image © Park Hill Estate, Sheffield – 1962. Image © Arch Press Archive RIBA Library Photographs Collection

Park Hill, Sheffield. Image © Park Hill Estate, Sheffield – 1962. Image © Arch Press Archive RIBA Library Photographs Collection Jules and Gabriel engaging in play at a public playground in Porto Covo, Portugal. Image © Jules Verne Times Two via Wikipedia, under license CC BY-SA 4.0

Jules and Gabriel engaging in play at a public playground in Porto Covo, Portugal. Image © Jules Verne Times Two via Wikipedia, under license CC BY-SA 4.0 Children in a makeshift wooden shanty (“Jongensdorp”) constructed in an Amsterdam-Oost lot, mid-20th century. Image © Public Domain (via Wikimedia Commons, Anefo collection)

Children in a makeshift wooden shanty (“Jongensdorp”) constructed in an Amsterdam-Oost lot, mid-20th century. Image © Public Domain (via Wikimedia Commons, Anefo collection)