Health reporter Helena Vesty was granted special access to see a procedure just being brought to the UK – as Manchester hospitals are among the first in the country to carry out the operation that could change thousands of lives Surgeons Sean Loughran (left) and Professor Sadie Khwaja worked for two years to bring a groundbreaking operation to Manchester(Image: Kenny Brown | Manchester Evening News)

Surgeons Sean Loughran (left) and Professor Sadie Khwaja worked for two years to bring a groundbreaking operation to Manchester(Image: Kenny Brown | Manchester Evening News)

Lying on an operating table, Dr Waseem Gill’s heartbeat soundtracks a clean, white room with a clinical metronome.

Two incisions are made into his neck and chest, and two surgeons begin searching through cords and strands, like vines in a thick jungle.

Inside Dr Gill’s body, a tiny box is being wired into the nerves. It might seem drastic, but the alternative can kill.

Get news, views and analysis of the biggest stories with the daily Mancunian Way newsletter – sign up here

A month later, Dr Gill’s anaesthesia has long worn off, and he sits in a different room of Trafford General Hospital. ‘For the first time in your life, your tongue is going to move without you telling it to’, an expert in the technology tells him.

At the push of a button, Dr Gill’s tongue does in fact shoot forward, sticking out just beyond his lips. And his natural instincts had nothing to do with it.

Dr Gill suffers with sleep apnoea – one of the world’s most prevalent, and destructive, sleep disorders.

Dr Waseem Gill was shocked to learn he had severe sleep apnoea(Image: Kenny Brown | Manchester Evening News)

Dr Waseem Gill was shocked to learn he had severe sleep apnoea(Image: Kenny Brown | Manchester Evening News)

Sleep apnoea stops sufferers from breathing as their tongue or soft palate relaxes, narrowing or even blocking their airway. It causes symptoms that are all-too-familiar to many of us – snoring, waking up a lot in the night, waking with a dry mouth or headache, suddenly jerking in your sleep.

And there’s plenty of symptoms that affect waking life – getting up feeling as unrefreshed as when you went to bed, sleepiness in the daytime, irritability, and increased likelihood of suffering accidents. It can increase the long-term risk of a stroke and heart disease.

People with OSA are advised not to drive in case they crash as a result of being sleep-deprived, and are also more likely to have an accident while operating equipment.

Yet, there is relatively little research about the true scale of the problem.

The procedure has been around for a decade elsewhere in the world, but is just being brought to the UK(Image: Kenny Brown | Manchester Evening News)

The procedure has been around for a decade elsewhere in the world, but is just being brought to the UK(Image: Kenny Brown | Manchester Evening News)

One study published in the British Medical Journal says the most common form of the condition, called obstructive sleep apnoea (OSA), affects an estimated 1.5 million adults – but 85 per cent of those people are undiagnosed, and go untreated. Only an estimated 330,000 adults are currently being treated.

Other sources say the figure is far higher. Based on predictions about rising obesity, which can contribute to the condition, the Sleep Apnoea Trust claims as many as 10 million people in the UK suffer from OSA – with up to four million of these suffering either severely or moderately.

Dr Waseem Gill was one of those hundreds of thousands who had no idea they had sleep apnoea. Even as a GP himself, now semi-retired, he’d put his symptoms down to ageing. To the fatigue from years of working, unsociable hours. The exhausting joys of raising a family.

“I was having symptoms suggestive of sleep apnoea – getting up tired in the morning, in the car after long distances driving, watching TV.

“I wondered if I had it, but never thought it would be severe,” Dr Gill told the Manchester Evening News. “I just thought, ‘am I getting old? Is this what it’s like?’ I wasn’t convinced I had anything wrong with me, even being in medicine.

“I just wondered if it was the ageing process. But every day I’d be getting excessively tired, waking up unrefreshed, groggy.”

Dr Gill says he is ‘fixing himself for retirement'(Image: Kenny Brown | Manchester Evening News)

Dr Gill says he is ‘fixing himself for retirement'(Image: Kenny Brown | Manchester Evening News)

A widower with three grown children, Dr Gill’s snoring didn’t disturb anyone in his home. But friends didn’t spare him when it came to their golfing trips.

“When I go on a golfing holiday with the lads, they tell me ‘you snore like a train’”, Dr Gill laughed.

Finally, the 64-year-old started getting tested and was referred to a sleep clinic.

The GP explained: “I was quite surprised to find out I have severe sleep apnoea. I stop breathing 47 times per hour on average.

“Stopping breathing – hypoxia – causes other problems. I realised I was at increased risk of other health problems.

“I’m almost retired and you want to use your energy for other things because you’re too busy working when you’re in your 20s and 30.

“But I’m so tired now I can’t do anything. I want to have early mornings. I thought I best do something about it.”

That something might seem alarming, but Dr Gill had exhausted the options.

The size of the implant(Image: Kenny Brown | Manchester Evening News)

The size of the implant(Image: Kenny Brown | Manchester Evening News)

OSA is typically treated with continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) machines. It worked for a while, said the south Manchester resident, but the hefty, intrusive Hannibal Lecter-style mask involved became a problem.

“Even though I’m a medic, I’m a bit of a terrible patient,” said Dr Gill. “I ironically don’t really like hospitals, I managed to wear the CPAP machine for about four or five hours and unless you wear it for that, it doesn’t really work.

“After a few months I felt encouraged, then I started pulling it off at night in my sleep. It felt claustrophobic.

“I tried to persevere, but the symptoms returned.”

Instead, Dr Gill found out about the hypoglossal nerve stimulation implant procedure and was told by doctors that he fit the criteria.

The procedure takes around an hour, with patients planned to be sent home the same day(Image: Kenny Brown | Manchester Evening News)

The procedure takes around an hour, with patients planned to be sent home the same day(Image: Kenny Brown | Manchester Evening News)

The procedure involves implanting a small device in the chest to stimulate the hypoglossal nerve, which controls the movement of the tongue.

No bigger than a thin matchbox, the pacemaker-like device is inserted under the skin of the chest hour-long operation.

The device is connected to a wires that are tunnelled under the skin – one to sense when the patient is breathing, and another connected to the nerve that moves the tongue forward.

The device sends an electrical pulse to the tongue, stopping it from blocking the throat and maintaining a clear airway.

The treatment has been completed thousands of times in the United States for around 10 years, and is being hailed as a major breakthrough that could change lives.

But the procedure is only just being brought to the NHS. And the ear, nose and throat team at the Manchester Royal Infirmary, which is run by Manchester University NHS Foundation Trust, are the first team outside of London to perform the procedure.

Of approximately 30 cases that have been treated in the UK. Dr Gill is the 14th in Manchester, after operations began in the city in July 2024.

The UK cases are part of a trial to gather data to decide if the results are good enough, and the technology cost effective enough, to be provided on the NHS more widely.

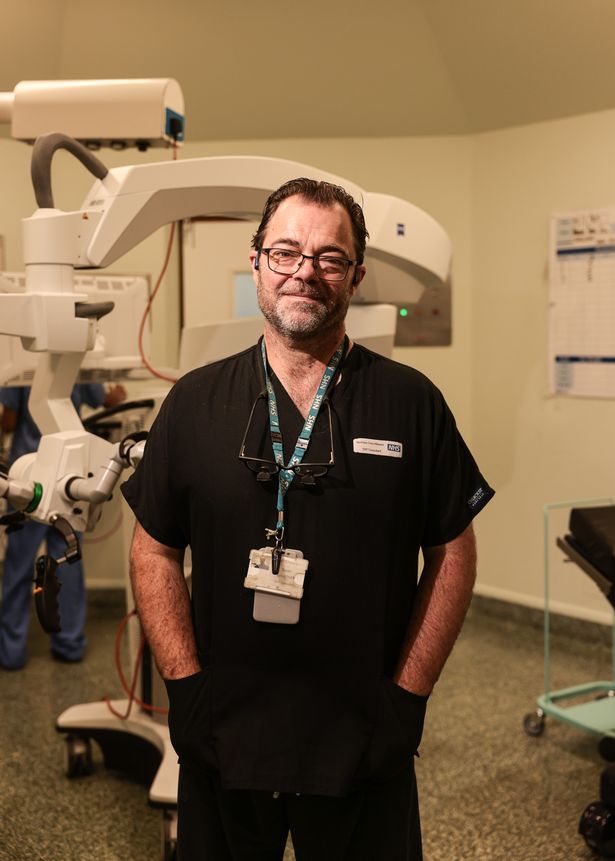

Consultant Sean Loughran(Image: Kenny Brown | Manchester Evening News)

Consultant Sean Loughran(Image: Kenny Brown | Manchester Evening News)

Surgeons Professor Sadie Khwaja and Sean Loughran worked for two years to bring the procedure to Manchester, and their initial results have been ‘excellent’ says Mr Loughran.

He first found out about the technology in a journal, and was thrilled to see ‘phenomenal results’ for patients after sleep apnoea has been characterised by a ‘long history of bad operations’.

“We’ve not any useful, good tools like this for many, many years,” he explained. “And there’s a long history of good results with this now.

“Liverpool is due to start these procedures soon, Leeds and Birmingham are looking at it too. There’s a huge population of patients that can benefit from it.”

Professor Sadie Khwaja looking down the microscope as the surgeons search for the right nerve fibre(Image: Kenny Brown | Manchester Evening News)

Professor Sadie Khwaja looking down the microscope as the surgeons search for the right nerve fibre(Image: Kenny Brown | Manchester Evening News)

Professor Khwaja added that sleep apnoea is becoming more and more common, and sufferers have previously been ‘limited in the options available’.

“Normally, [in the UK] we wait for the Americans to do it first, wait for the data that proves it actually does work. We’re not inventing something new here, it’s been out for a decade, it’s had a hundred thousand patients,” says the medic.

“You might say we’re behind the curve, but in the UK we generally like to wait and see ‘is it really what it is?’ Does it do what we want to achieve?”

“It’s really life-changing,” explains Dr Khwaja. “If you do not have a good quality of sleep, it impacts your stress levels, your general health and well-being, your blood pressure definitely, and your cardiac risks.

“In one fell swoop you’re tackling all of those factors. It changes those people into a newer person. That storyline is what we’re seeing coming through in our results.

“And what’s the alternative? All of these people have been given the option of having a mask stuck to their face every night for the rest of their lives, and a lot of them just couldn’t tolerate it. They had no other option.”

“Every procedure has its problems and complications, it’s not something I’d really want to do unless it was necessary. But I did my research and the risks are low,” said Dr Gill, gowned up and waiting for his operation.

“It’s really exciting, I’m pleased to be part of the cohort who are innovators. It shows the NHS is still innovating, too.”

The operating theatre team at Trafford General Hospital(Image: Kenny Brown | Manchester Evening News)

The operating theatre team at Trafford General Hospital(Image: Kenny Brown | Manchester Evening News)

A few minutes after I speak to Dr Gill, he is in the operating theatre and being put to sleep. A small cut is made into Dr Gill’s neck and chest – he’s got a ‘nice neck’ for the job, according to the surgeons.

“A nice neck means they generally aren’t overweight,” explains Professor Khwaja. “Their problem generally is the size and position of their jaw, which affects the position of the tongue.

“When you operate on those types of people, it’s a nice surgery to do and our record time is 55 minutes.

“Other patients might have a slightly shorter neck, a bit thicker in size. It means the surgery might have to be a little bit deeper and it just requires a little bit more time, because you just want to be safely getting in there and finding our nerve.”

Two incisions are made into the neck and chest to fit the device(Image: Kenny Brown | Manchester Evening News)

Two incisions are made into the neck and chest to fit the device(Image: Kenny Brown | Manchester Evening News)

They must find the right fibre of the hypoglossal nerve that pushes the tongue forward – like searching for one slim strand at an unravelling end of rope, explains Mark Chambers.

He’s an expert from Inspire, the company that makes the groundbreaking technology, who advises surgeons during operations.

The tongue could move around unexpectedly if the device is connected to the wrong fibre.

“This is the variation in all of us – sometimes those fibres are already neatly separated for us and it makes life a lot easier,” says Professor Khwaja. “Other times we have to tease out that separation.”

Dr Gill’s tongue is hooked up to leads that can prove the surgeons are handling the right nerve strand. The nerves are stimulated and the muscle produces deep bass notes and buzzing electrical feedback through the leads to signal which fibre the surgeons have – the bubbling sounds of the human body.

“It’s the noise of the nerve whinging at you,” jokes Sean.

Dr Gill’s procedure was completed smoothly(Image: Kenny Brown | Manchester Evening News)

Dr Gill’s procedure was completed smoothly(Image: Kenny Brown | Manchester Evening News)

Once the right fibre is found, the surgeons wrap a cuff around it which an electrical charge can flow through. Tiny wires are then tunnelled beneath the skin and above the muscle to connect the implant pulse generator.

When the patient breathes in, the sensor lead around the ribs detects a pressure change and sends a signal to the matchbox-style device, which in turn sends a signal along another lead to the nerve. A charge is then issued to stiffen and push the tongue forward.

But when the tongue jumps forward, there’s no pain or discomfort, just movement – as the device is connected to a motor rather than sensory nerve.

It’s fitted to the right side of his body, in case the patient ever needs a heart pacemaker on their left.

The surgeons check the systems are connected and working, and Dr Gill’s neck is stitched up and glued back together.

The operation is over and just hours later, after an x-ray to make sure everything is sitting where it should, the granddad-of-two is back at home recovering.

Join our Manc Life WhatsApp group HERE

A month later, Dr Gill is back at the hospital to have the stimulator inside his body switched on. He had a slight complication after surgery, with some swelling to his neck, but that’s reducing now, and he can’t feel the wires and implant under his skin, he says.

Mark is here again, and begins activating the implant for the first time to check it’s working on a waking Dr Gill, and train him up in using the technology.

Mark tests different strengths of electrical pulse to find a level that pushes the tongue forward but isn’t intrusive so that Dr Gill will remain soundly asleep when he turns the implant on himself at night.

Patients go home to acclimate to a low level of impulse, which can then be raised in small increments to find the level that will achieve their best night’s sleep.

Patient Waseem Gill’s tongue moves forward as the implant is tested with electrical impulses at his activation appointment with Mark Chambers (left) and Sean Loughran (right)(Image: Jason Roberts /Manchester Evening News)

Patient Waseem Gill’s tongue moves forward as the implant is tested with electrical impulses at his activation appointment with Mark Chambers (left) and Sean Loughran (right)(Image: Jason Roberts /Manchester Evening News)

Patients use a handheld controller the size of a computer mouse to turn the device when they go to bed, and patients choose a countdown window so that the pulses don’t begin before they’ve fallen asleep.

A timer is set for how long the patient wants to sleep for, so that the device will automatically switch off around the time they expect to wake. It can also be stopped manually with the controller, paused for a short period in case they get up in the night for the toilet, and be turned up and down.

Dr Gill chooses a 30-minute window between switching the device on and impulses starting, a 10-minute pause window, and a total duration of seven hours.

“It’s odd, sort of like you’re a puppet,” says Dr Gill, his tongue protrudes as the device is checked with test electrical pulses.

But, tellingly, he admits: “Honestly, I’d be so happy with seven hours of sleep.”

Dr Gill hopes to encourage people to seek out the care they deserve and live in better health as they age(Image: Jason Roberts /Manchester Evening News)

Dr Gill hopes to encourage people to seek out the care they deserve and live in better health as they age(Image: Jason Roberts /Manchester Evening News)

I walk out of the hospital with Dr Gill, down the corridors and towards home. It’s a hopeful future that could see a huge improvement on his quality of life, he says, one where he prioritises properly taking care of himself for the first time in decades.

Professor Khwaja says Dr Gill is one person amid a wave of new referrals, as people are starting to recognise they might not have to fight through their days amid chronically terrible sleep.

“I’m looking forward to feeling more energetic,” he explains. “I would always just get on with things even if I was in quite a lot of discomfort – working 80 hours in a row as a young medic

“Maybe we were wrong or stupid to do that, it’s not this way anymore, but you got on with it and got used to it.

“Now, I feel like I’m repairing myself for retirement, I’ve had two new hips as well!

“We should all give yourselves a bit more time to think about ourselves, you just can’t ignore yourself forever.”