Another week, another round of royal revelations. Following swiftly on from the publication of Andrew Lownie’s bestselling denigration of the Duke and Duchess of York – Entitled, there is now another tell-all account of the royal family: Valentine Low’s Power and the Palace. It has recently been serialised in the Times (appropriately enough, given that Low is that newspaper’s royal correspondent) and purports to offer a well-sourced and factually accurate account of the relationship between politics and the royal family over the past few years.

We can expect a steady stream of such volumes for some time to come

Low is a serious writer, whose excellent 2022 book Courtiers was a particular standout in an often tawdry genre, and so the stories within Power and the Palace should be taken seriously. Thanks to recent published excerpts, readers have learnt, amongst other things, that the late Queen supported a Remain vote in Brexit on the grounds that ‘it’s better to stick with the devil you know’. They will also have read that the so-called ‘sovereign grant’, agreed by the coalition government in the early 2010s, ended up being considerably more generous than originally planned, and that after Boris Johnson illegally prorogued parliament in 2019 in what his critics alleged was an attempt to enable a no-deal Brexit, he failed to apologise to the Queen despite the expectation that he would. (I remember Private Eye going a step further at the time and noting that the palace was surprised that Johnson didn’t resign altogether as a matter of honour; clearly they had forgotten who they were dealing with.)

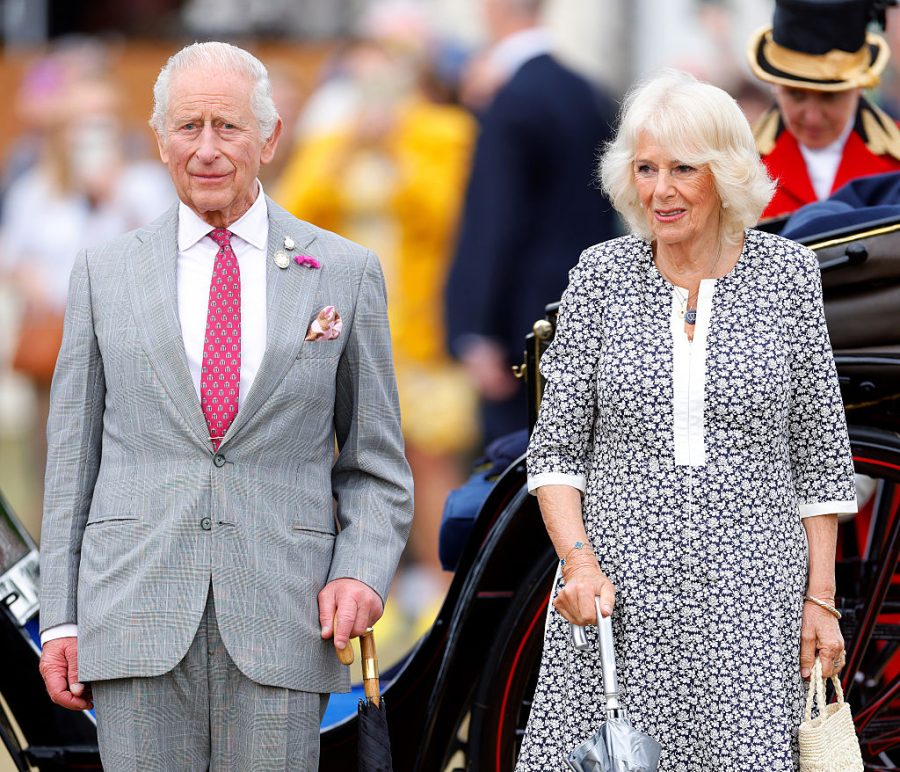

Some of the revelations are largely light-hearted, such as the Queen’s penchant for doing the washing up at Balmoral (albeit slightly ineffectively – a dishwasher was pressed into service afterwards) and her sending Barack Obama to bed when he was enjoying himself too much at a banquet at Buckingham Palace. Others, such as today’s story that Camilla’s personal support for rape crisis centres stems from an incident as a teenager when she narrowly avoided serious sexual assault on a train and ensured that her attacker was arrested, are more sombre in nature and all the more revelatory as a result.

Still, for all the front-page headlines, both the Low and Lownie books suffer from the same problem. Firstly, although both offer detail that few, if any, readers would have previously been aware of, the stories are really just offering well-researched anecdotes rather than anything genuinely revelatory for the most part. And when a truly interesting detail emerges – such as the Queen’s apparent rejection of Brexit – the question immediately is raised of where the information came from. It is no surprise to find that the source in this case was George Osborne, former Chancellor and Remainer-in-chief.

There are a huge number of books about the royals, historic and contemporary, published every year. Many are laudatory, a smaller number condemnatory, and all have their own reserved place on the bookshelves of your average bookshop. Commentators and biographers know that, unlike other public figures, the royals are unlikely to sue or comment on the specific veracity, or otherwise, of the stories contained within their pages, meaning that it is possible – should they wish – to get away with single-sourced accounts from dubious and often partisan quarters.

Given that the best-selling non-fiction book of all time in this country, Prince Harry’s Spare, was chock-full of similarly incredible claims, we can expect a steady stream of such volumes for some time to come. Still, as a great woman once said, ‘recollections may vary’, and it is important to retain an element of detachment while reading some of these stories: just because you might wish to believe something to be true doesn’t necessarily mean it is, after all.