It started with a text message and the promise of a potential career change.

“We have an open new position for you here. Can I send more details.”

The message was from an Irish number and claimed to be sent by a woman named ‘Amelia’ supposedly working for a well-known Dublin-based recruitment agency.

After a few cordial back and forth messages, came a query about my age.

“May I know are you above 21 years?” Amelia asked.

“Yes,” I replied.

“Alright, the person will text your What-App within an hour. Thank you and have a nice day.”

“What is What-App?” I asked.

“Alright, we will send you all information via What-App,” came the reply.

Then, nothing.

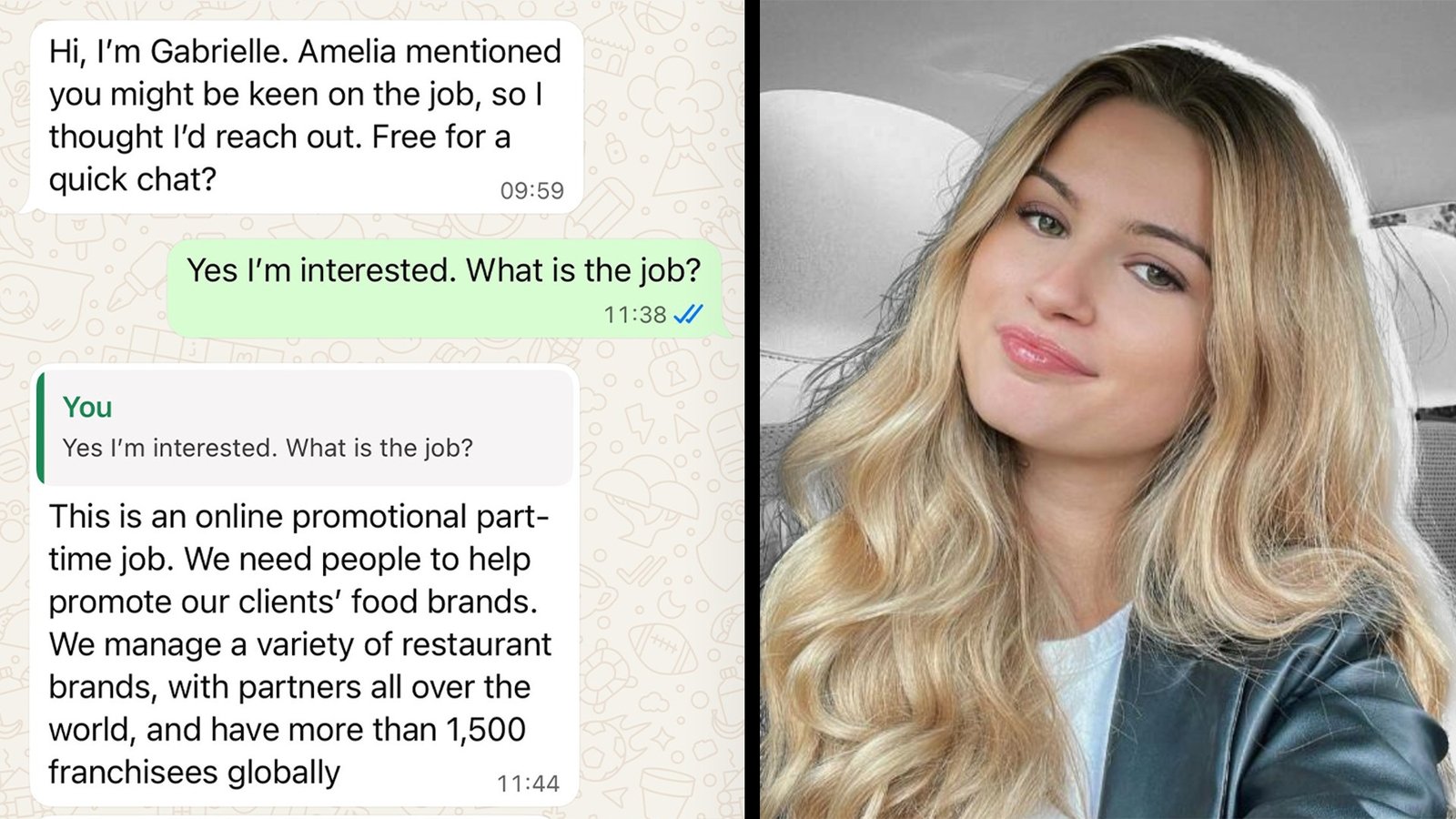

The initial message from the supposed ‘recruiter’

This kind of message will be familiar to many people. A hint of opportunity and just enough detail to seem credible.

In reality, it was the opening step in a scam that has been circulating widely in recent months.

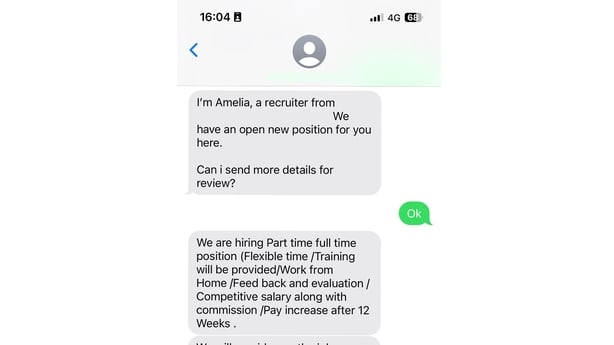

The follow-up came the next day. This time it wasn’t Amelia, but a new contact on WhatsApp with a glamorous profile picture.

“Hi, this is Gabrielle,” she wrote. “Amelia passed me your details. Are you free for a quick chat?”

“Yes, I’m interested. What is the job,” I replied.

The follow up from ‘Gabrielle’ via WhatsApp

While waiting for ‘Gabrielle’s’ follow-up I quickly ran her WhatsApp profile photo through several reverse image search tools. These are tools which can be used to try find out where else on the internet a specific image has previously been posted.

The image looked convincing at first. But when no identical match could be found, I tested it with software that detects signs of artificial intelligence (AI).

The analysis suggested the image of Gabrielle, apparently sitting in her car, was 95% likely to have been generated by AI.

Analysis suggested ‘Gabrielle’s’ WhatsApp profile photo was 95% likely to have been AI-generated

When Gabrielle finally outlined the role, it sounded straight-forward: a part-time online job helping “promote food brands” by leaving star ratings.

The work would take “30 to 50 minutes a day,” and applicants could earn between €50 and €160 daily.

Payments, she assured, could be withdrawn by bank transfer, Revolut, cryptocurrency or IBAN.

When asked who the employer was, she shared a link to the official website of Yum Brands, the US company behind KFC, Taco Bell and Pizza Hut.

But when it came time to register for the “job,” the link changed. Instead of Yum’s genuine site, I was directed to a look-alike domain entirely unrelated to the real company.

There is no evidence the company has any connection to the site.

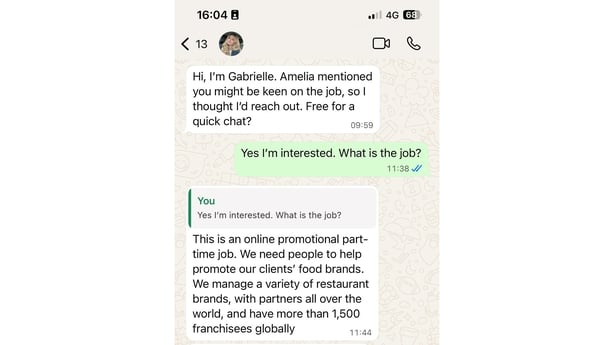

The platform sent by ‘Gabrielle’ was designed to look like a legitimate brand’s website

To make the pitch sound more credible, ‘Gabrielle’ claimed she was “the person in charge in Ireland.” Asked where she was based, she said Dún Laoghaire, despite her phone number carrying a UK code.

She even steered the conversation into everyday small talk, asking what industry I worked in, where I lived, and whether I’d had lunch.

The type of scam Gabrielle and Amelia were running is what is known as a task scam.

Task scammers target people looking for remote jobs and victims are asked to carry out simple online jobs such as liking posts, leaving reviews, or placing dummy orders. They’re then shown their “earnings” on a platform or app.

But after a limited number of tasks, they’re told they must pay to “upgrade” their account in order to access the money earned.

“It’s targeting people who are often out of work or vulnerable. If you’re already lonely, maybe at home, that’s even more amplified. And then, they’ll add urgency,” explained Robert McArdle, Director of Cybercrime Research at Trend Micro, a global cybersecurity firm.

“They work, because these are preying on people who are having a hard time in their life,” he added.

The scam is designed to exploit the sunk-cost fallacy according to Mr McArdle – once people have put in time and effort, they’re more likely to keep paying rather than walk away.

“When you’re a social engineering person, there’s a whole bunch of psychological tricks that are very well established. They add messages like, ‘we need you to put the money in right now. Otherwise, you lose the earnings you’ve made so far.’ So that urgency and fear, it’s a strong human emotion,” Mr McArdle said.

Robert McArdle is Director of Cybercrime Research at Trend Micro

Eventually I agreed to move forward with the opportunity and told Gabrielle I was keen to do the job she’d advertised.

That was the trigger for the next stage of the scam.

She sent me a link and an invitation code, but instead of pointing to Yum!’s real website, it opened a convincing copy dressed up with the company’s logos and branding.

Records show the yumbrandscrypto.com site she sent was only registered in April this year.

It was set up in a way that allowed the same website to be copied and relaunched under slightly different names. This tactic is common in online fraud.

Once a website is reported or blocked, scammers often simply set up a near-identical one in hours, keeping the operation alive.

“If you search and the first hit is people saying, ‘I got scammed by this,’ then that’s burned. They can’t use it anymore. So, every couple of weeks or months they just cycle on to the next impersonation,” Mr McArdle said.

Research published in August by Trend Micro shows these kinds of disposable website domains aren’t unusual.

Scam operators often register dozens at a time through low-cost offshore registrars, recycling the same website template until each domain is reported and shut down.

“Setting up a domain you can do for as little as a couple of euro. And then to have a believable website that looks like the real thing, that’s gotten substantially easier because of AI,” he added.

A quick search online revealed a similar site to the one sent by Gabrielle, yumworkplatform.com, was registered last December but is now suspended after being reported for abuse.

Online forums in Germany warned users to avoid it, describing the same pattern of fake balances followed by demands for repeated deposits.

Another, yumsearchengine.com, has been taken offline for “suspected phishing.”

Digging deeper into the site’s code revealed that alongside the English branding were hidden Chinese phrases such as “How long does a withdrawal take to arrive?” and “Top-up successful.”

The same codebase also contained prompts in Hindi, covering fields like “Mailbox cannot be empty” and “Birthday format must be 03/24/1998.”

Robert McArdle says these traces point to industrialised scam hubs in Southeast Asia and beyond.

“Generally, what you are seeing there is the fact that this scam has some Chinese or Hindi roots to it. A lot of these task scam criminal groups we would associate with groups coming from that part of the world, India and China, Southeast Asia as well.”

When I stopped engaging with Gabrielle, she continued to check in asking me if I needed any help registering.

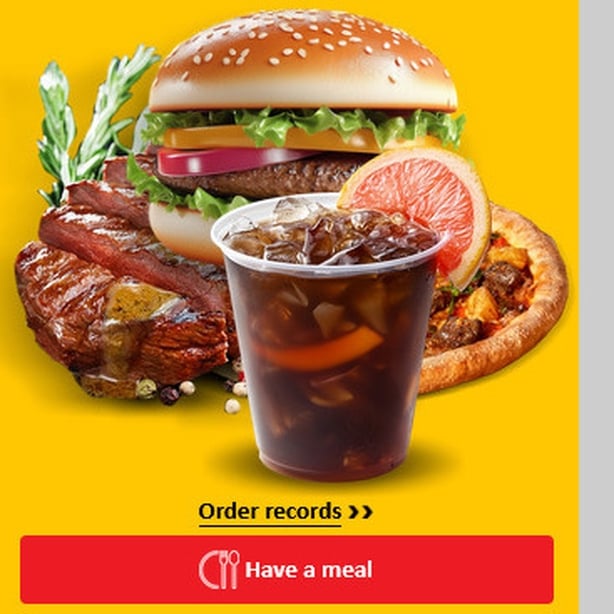

Eventually I proceeded and was brought into a slick-looking app plastered with ‘Yum!’ logos and photographs of food.

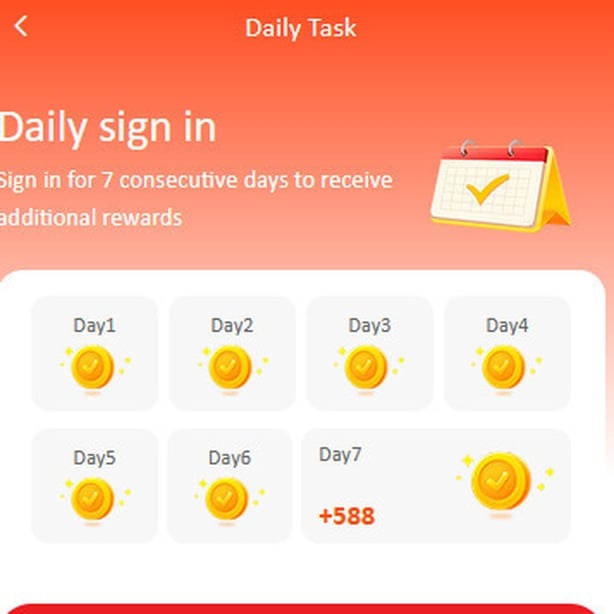

At the top of the screen, a balance appeared with a “trial bonus” of €288 and the promise of daily rewards just for signing in.

Tasks included leaving star ratings and clicking through dummy orders, each action supposedly adding to my earnings.

The platform promised daily rewards just for signing in

Unsurprisingly, withdrawals were blocked until I “bound” my account, and a flashing diamond urged me to upgrade my membership to unlock higher payouts.

In other words, to access the money I’d supposedly earn by carrying out tasks, I first had to hand some over.

Withdrawals were blocked until I “bound” my account

The mechanics of scams like this one may look crude once exposed, but the scale is anything but.

Trend Micro’s research estimates that task scams have already defrauded victims of billions of dollars worldwide, with tens of thousands of people caught up in schemes that present themselves as routine online work.

“The scam itself is not new,” Mr McArdle said.

“Where they are sophisticated is the targeting of the human is well thought out. What the average internet user can do is be aware of these scams, understand how they work, so that if they get targeted, they don’t go so far as to actually lose money.”