Anyone with an interest in Manchester’s live music scene will likely have had a run-in with the Albert Hall on Peter Street. Be it for a sold-out concert, a club night or as one of the many venues frequented by Manchester Psych Festival, the venue has attained an acclaimed reputation due to its Neo-Baroque architecture, unique wrap-around mezzanine, and gorgeous stained-glass windows.

It’s rare to encounter a person who has attended an event there that isn’t willing to sing its praises. The other universal claim though, is the intrigue into what exactly the building accommodated in its past. Many assume it was simply just a church, but this gothic palace has considerably more extensive lore which necessitates a deep dive to give life to a true veteran of Manchester’s Peter Street and its past.

Where it all began…

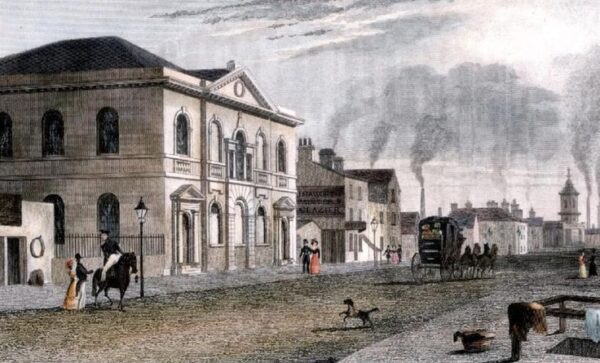

The site of Albert Hall, located on the ever-bustling Peter Street, was documented as a place of religious worship as early as 1793, when it was home to The Jerusalem Temple. The congregation followed a unique religious practice derived from the teachings of Emanuel Swedenborg – a scientist and theologian based in Sweden that had amassed a cult of followers around the world. Considered a branch of Christianity, the religion was broadly known as The New Church, a name which captures the religion’s thesis of reinventing traditional Christianity – a practice that was in decline.

The former site saw several structural transformations, evolving from a simple church with a lumber yard to the home of a school and one of Manchester’s earliest stages: the ‘Grand Theatre of Varieties’. The three-floor auditorium was to the left of the Temple, and for over a century it accommodated theatre performances, concerts, choirs, and even the circus.

Credit: Department of Prints and Drawings @ HMSO

Credit: Department of Prints and Drawings @ HMSO

The site of the Hall was converted into a technical school, which was vacated by The New Church in the late nineteenth century. The site sat vacant until around 1908 when the demolition of the derelict building began.

The Hall then came under the ownership of the Manchester and Salford Wesleyan Mission (MSWM), whose purpose was to provide aid to any and every Mancunian in need. Though a Methodist operation, the organisation was led solely by volunteers who provided help to anyone who needed it: the unemployed, those without faith, those without financial means – any ‘lost soul’. Albert Hall was one of several sites owned by the group across Greater Manchester, and this site was chosen due to the close proximity to local communities who had been poverty-stricken by the decline of industry in the area.

The unique, gothic and baroque design of the building has also intrigued those from the local area and beyond since the building’s establishment. Architecturally, the hall is an astounding example of Edwardian optimism: W.J. Morley, a Yorkshireman with a well-established presence in the architectural community, was commissioned as his work was considered a look to the future, delving into more ornate, intricate designs and departing from the simpler styles of the preceding Victorian era.

Credit: Frankie Austick @ The Mancunion

Credit: Frankie Austick @ The Mancunion

The four-storey building was not simply a church, but a pillar for the local community, in that it was not just a place of worship; rather, it acted as a social and cultural melting pot of varied means. Here, talks from notable speakers such as Winston Churchill were hosted, as well as People’s Concerts with performances by Mancunian artists in aid of various charitable projects. With the ground and sub-zero floors containing classrooms, kitchens, and bedrooms, it provided an array of social spaces in which members of the public could find sanctuary and support.

The first half-decade of Albert Hall’s existence is documented almost solely by newspaper listings for concerts, harvest festivals, speeches, and sermons from various resident reverends. The lack of extensive photographic documentation is due to the majority of the missionary’s files being destroyed during the Blitz – we consequently rely heavily on a handful of images and first-hand accounts to paint the picture. What is known, though, is that Albert Hall is said to have continued to provide sanctuary and aid to those in the vicinity until the late sixties.

Albert Hall, itself, remained architecturally unscathed by the Blitz, with congregations gathering throughout the war. One first-hand encounter recites the congregation’s continuing song as the bombs fell around them, testifying to the resilience of Manchester’s soul. She describes how when the bombs got closer, they simply sang louder; in harmony with the still-in-place heart of the building, the organ.

However, it seems that just like the rest of the nation, the events of the Second World War left a lasting impression on the building. The demand for its services no doubt exceeded their capabilities. This is also evident architecturally, with underfunded maintenance work appearing most evident in the doorways of the building; the majority were structured using recycled doors from a local shut-down school. The combination of these financial struggles with increasingly declining faith post-war are likely to have been the final nail in the coffin, and the MSWM vacated the site around the late 1960s, initiating a near fifty-year rest for Albert Hall.

Back with a Bang

The ground-level space below, used initially for classrooms and a smaller meeting hall, operated as a car dealership into the seventies, when at some point it met a similar fate to the Hall above. The building sat fully derelict, used for nothing but storage, until Cougar Leisure Inc. saw potential once more in utilising only the ground-floor space; the building was re-opened as the nightclub Brannigans in 1990, with only the ground and sub-level floors in use. Whilst renovated to accommodate the new bar, seating areas, and dancefloor, the site thankfully retained the majority of its iconic structural features, such as its stained-glass windows, ornate fern-green tiling, and meticulously handcrafted ceiling patterns.

The venue was somewhat a success – whilst it became notorious for its cheap grub and drinks, it was still able to cement itself as a key part of Manchester’s nightlife scene. Over time, the club went on to garner a notorious reputation for being rowdy, outdated, and generally unsafe. It struggled with attracting the wrong crowds, becoming the opposite of the safe environment the building was once intended to be.

One review left on Yelp in March 2010 perhaps summarises it best: “This is where manners, taste and tact go to die”. After years of underinvestment and run-ins with the law, Brannigans closed its doors in 2011, in what may be seen by some as a positive twist of fate.

Reinvention of the Wheel

The closure of Brannigans is where the Albert Hall of today began to come to fruition. The ageing hall, plagued with decay from years of neglect, was considered nothing but a remnant of a fading, religion-bound past to many. However, the forces behind Northern Quarter’s Trof, who surprisingly already also had Gorilla and The Deaf Institute also under their belt, saw potential. They purchased the site for an undisclosed amount in 2012, immediately breaking ground on a £3.5 million renovation. For the first time in almost half a decade, Albert Hall was set to emerge from the dust as a new and improved social spot.

In a short matter of time, Albert Hall was brought back from the dead. The venue was ready in time to host a small introductory series of gigs in late 2013, as part of the Manchester International Festival. This was the first documented use of the space for a public event in around 44 years – a milestone achievement for a space that had for so long been in jeopardy of being lost to time. The vision was never to truly ‘compete’, but to co-exist with well-known and established competitors across the city, something that may not seem too ambitious nowadays.

Credit: Frankie Austick @ The Mancunion

Credit: Frankie Austick @ The Mancunion

From 1980 to 2001, Manchester suffered from a 10% decrease in population as a result of decades of financial neglect from the government. In this time, the music scene that Manchester is renowned for having had little to no protection from local authorities, let alone funding to keep it going. The scene was self-reliant, and with many members of the audience choosing to leave the city, the loss of foot traffic led to the loss of many iconic venues including the Haçienda – a cultural icon lost to time after decades of being funded by the independent Factory Records.

Thankfully, a growing appreciation for the heritage of Manchester’s music scene began to attract new generations of students to the city, with the population increasing by 25% from 2001 to 2011. The team behind Trof saw that the world in which Brannigans existed was different to the world the Albert Hall would exist in as a live entertainment venue: Manchester was not just a city, but a cultural hub. The forces behind Trof saw that people would travel to see a gig, simply to be involved in notorious crowds and witness the palpable delight of artists playing in the city: they excelled in seeing the potential in heritage.

In 2015, they joined forces with the founding CEO and director of Inventive Leisure to found Mission Mars, a new company with a vision to combine resources and assets to build up an extensive array of live entertainment venues and restaurants. Mission Mars went on to become somewhat of a hospitality legend, striving to nurture innovation, sustainability, and people: Albert’s Schloss, which originated from the ground-floor level of the Albert Hall building, is now a successful franchise, while Mission Mars have found even more success in their 2017 acquisition of Rudy’s neopolitan pizza restaurants and the continuing supremacy of the Revolution and Revolucion de Cuba bar chains.

In its time as the venue we know and love, Albert Hall has hosted thousands of events to hundreds of thousands of people. Most notably are its concerts; the venue is unique in that it bridges the middle ground between smaller and big-name artists – offering a level of intimacy that you’ll struggle to find elsewhere. Offerings over recent years have included PJ Harvey, Mitski, alt-rock pioneers Pixies, budding pop-star Remi Wolf, indie-folk paragon Laura Marling, psychedelic R&B songstress Greentea Peng, and even noughties icon Kesha.

Albert Hall has also been a platform for countless names of emerging talent, being one of the stages that Stockport’s own Blossoms, international star Charli xcx, and world-renowned DJ and producer Fred again.. took to on their climb to the top.

Credit: Frankie Austick @ The Mancunion

Credit: Frankie Austick @ The Mancunion

Whatever kind of escapism takes your fancy, it can be found at the Albert Hall. In many ways, the Hall is still the community hub it initially was – the venue has been a cultural melting pot and a convergence point for likeminded souls long before we were breathing, and will probably remain so long after we breathe our last.