From a hill in Gatika, a village of 1,600 inhabitants about a half-hour drive from the Spanish city of Bilbao, the scars left on the land by the construction of the ill-fated Lemóniz nuclear power plant in the 1970s are clearly visible. High-voltage towers dot a green landscape sprinkled with small houses that live alongside the cables of a facility that was never put into operation.

More than 40 years after it was abandoned, dozens of workers are now busy building a new converter station next to the refurbished original substation. This is the starting point for the energy interconnection that, by 2028, will link the Iberian Peninsula with the rest of Europe — a “power highway” connecting the Spanish and French electricity systems through two 400 kV links from Gatika to Cubnezais, near Bordeaux.

Disused high-voltage towers in Gatika.FERNANDO DOMINGO-ALDAMA

Disused high-voltage towers in Gatika.FERNANDO DOMINGO-ALDAMA

It is an ambitious and technically complex project, as the route runs entirely underground and under the Bay of Biscay. But it is also not enough to end the Iberian Peninsula’s energy isolation. The interconnection will increase the electricity exchange capacity from the current 2,800 to 5,000 megawatts, but falls far short of the minimum required by Brussels.

“For the internal energy market to be truly effective, the Commission set targets of 10% of installed generation capacity for 2020 and 15% for 2030. And with this interconnection, we’ll barely reach 5%,” admits Juan Prieto, project director, during a visit to the works in Gatika.

View of the electrical interconnection works between Spain and France in Gatika.FERNANDO DOMINGO-ALDAMA

View of the electrical interconnection works between Spain and France in Gatika.FERNANDO DOMINGO-ALDAMA

In short, half a dozen interconnections like this would be needed to bring the Iberian Peninsula on par with the well-developed international grids of the other major euro-area economies: Italy, France, Germany, and the Netherlands. And a dozen more would be required to meet the target set for the end of this decade.

Europe’s dense continental network continues to run up against the barrier of the Pyrenees, leaving Spain and Portugal exposed when problems arise. This reality became particularly clear on April 28, a date that will be forever etched into the collective memory: the day of the first major blackout in the history of Spain and Portugal.

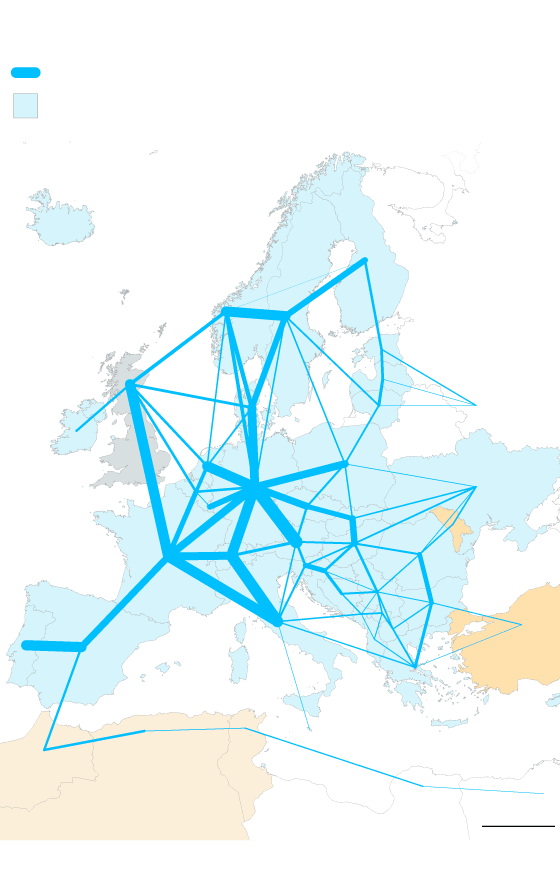

The European power grid

Interconnection capacity (MW)

United

Kingdom

Former

member

Countries synchronized

with the Continental European grid

Source: Ember Energy, ENTSO-E, Red Eléctrica.

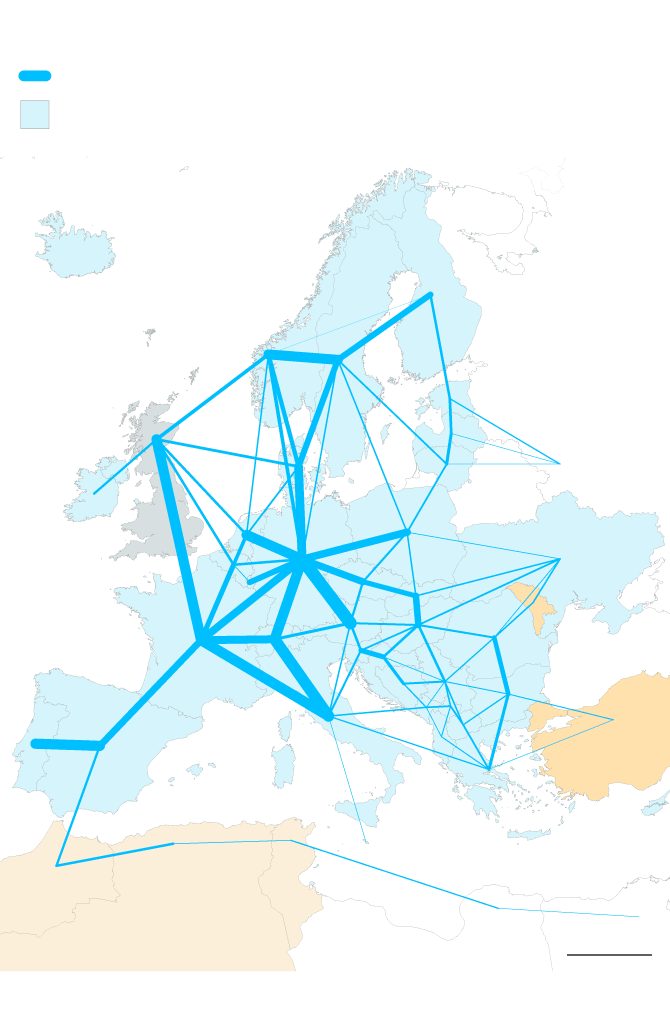

The European power grid

Interconnection capacity (MW)

United

Kingdom

Former

member

Countries synchronized

with the Continental European grid

Source: Ember Energy, ENTSO-E, Red Eléctrica.

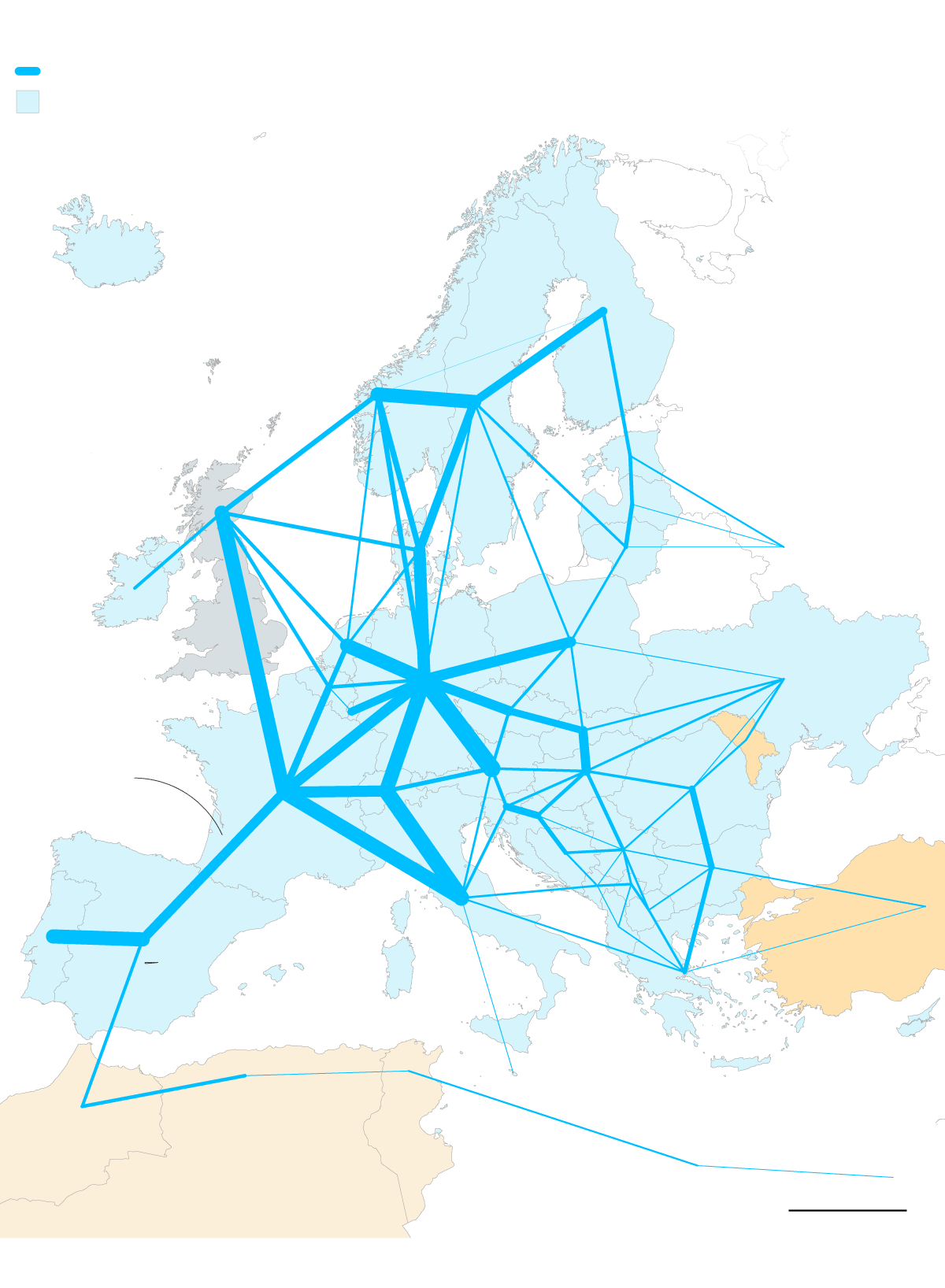

The European power grid

Interconnection capacity (MW)

United Kingdom

Former member

The Bay of Biscay interconnection will raise total capacity to 5,000 MW

Countries synchronized with the

Continental European grid

Source: Ember Energy, ENTSO-E, Red Eléctrica.

It lasted several hours, mostly during the day, but the unprecedented total blackout plunged both countries into a strange state of chaos and uncertainty. More than 50 million people suddenly became aware of the countless implications of losing power — that everything, absolutely everything, depends on having electricity. That we are far less prepared than we think — or than EU authorities would like, with their recent emergency kit, which many considered a joke. That blackouts may not be just a thing of the past, as was believed: recently, the Czech Republic experienced a taste of the same crisis. And that, despite the exemplary reaction of citizens, a few more hours of darkness would have made matters far worse. Only the rapid restoration of service prevented greater harm.

The Spanish government’s preliminary report arrived in mid-June, a month and a half after the blackout — weeks ahead of schedule, but not soon enough to stop rumors and finger-pointing. Especially at the renewable energy sector, which was immediately blamed.

The conclusions, in summary, indicate that there were prior fluctuations in the European power grid, that several overvoltage episodes led to the mass disconnection of generation plants, and that Spain’s state electricity provider Red Eléctrica de España (REE) and the distributors failed to contain the blackout using the safeguards intended to prevent a local problem from escalating into a binational disaster.

In terms of politics and business, blame was shared between REE and the electricity companies. From a purely technical standpoint, it was a strong wake-up call and an implicit acknowledgment that both infrastructure and regulations are lagging behind reality. This perspective helps explain the Spanish government’s two most notable actions since then: a substantial injection of funds to reinforce the grid and the announcement of significant changes in operational procedures — the regulatory framework that underpins the daily operation of the electricity market.

Leaving aside reports — the final ones are still pending, many of them at the EU level — three key conclusions can be outlined without fear of error, and they may help other European neighbors, like Germany or Denmark, which also have high penetration of wind and solar in their electricity mix. First, technical regulation: these generation sources, though inherently intermittent, could already be providing stability and voltage control. There is no technical reason why they shouldn’t. Second, storage — through pumped-storage hydro plants and, above all, batteries — is essential to support a safe transition to green energy. Third, and perhaps most obvious, the blackout would have been far less likely and shorter if the interconnection between the Iberian electricity system and the rest of the continent were at the level it ought to be by now.

The capacity of the cables connecting the Iberian Peninsula with its neighbors to the north, beyond the Pyrenees, has been stuck at 2.8% of installed generation capacity for years — far below EU requirements. The works underway in the Bay of Biscay — which are expected to be completed in 2028, much later than initially planned — will substantially increase that figure. But it will still fall well short of the target.

The Lemoniz power station with the sea retaining wall on the left.EL PAÍS

The Lemoniz power station with the sea retaining wall on the left.EL PAÍS

A concrete monolith embedded in a cliff on the Biscay coast is all that remains of the failed Lemóniz nuclear power plant. 2024 marked the 40th anniversary since its definitive shutdown. That was in 1984, when the Spanish government of Felipe González issued a moratorium on nuclear power, although the project had already been deemed unviable years earlier due to the combined pressure of the anti-nuclear movement and a fierce campaign of attacks by the now-defunct ETA terrorist group.

Next summer, submarine cables for the new interconnection will begin to be laid in front of the overgrown buildings. The project has also faced opposition. The movement Interkonexio elektrikorik ez (“No to the electrical interconnection” in the Basque language) has been protesting against the “power highway” with marches and posters that can be seen in Gatika and other towns in northern province of Biscay.

Meeting of members of the platform against the construction of the power plant in Gatika at the end of May.FERNANDO DOMINGO-ALDAMA

Meeting of members of the platform against the construction of the power plant in Gatika at the end of May.FERNANDO DOMINGO-ALDAMA

“It’s practically impossible to develop projects of this type without some friction,” acknowledges Antonio González Urquijo, regional delegate for Redeia in the Basque Country, who says that only 13 plots have had to be expropriated, compared to 75% of amicable agreements.

“This infrastructure will be here for decades. We’ll be neighbors; we don’t want it to be imposed,” adds Juan Prieto, director of the interconnection.

Twelve possible land routes were studied before arriving at the final one, 13 kilometers long (eight miles), which winds along existing tracks and paths to minimize impact, Prieto explains, adding that the high-voltage towers and cables built for Lemóniz will also be removed.

It is no coincidence that, although insufficient, the Gatika interconnection is on the list of Projects of Common Interest (PCI, essential for receiving EU funding), a category that also includes future pipelines intended to carry Iberian green hydrogen to the rest of the continent.

In the case of the electrical interconnection, it was recently announced that it will receive €1.6 billion ($1.87 billion) in funding from the European Investment Bank (EIB). The goal, in the words of European Energy Commissioner Dan Jorgensen, is for European citizens to “have access to clean and stable supplies, wherever they are.”

“Until we have a clear understanding of the sequence of events, everything remains speculative. But greater integration into the continental system should have acted as a buffer to prevent the blackout,” notes Georg Zachmann, an analyst at the Brussels-based think tank Bruegel. “In general, increasing the size of the system through greater regional integration should have acted as a buffer against internal shocks that could bring the system down.”

The German expert also criticizes the lack of clarity in the Spanish government and REE reports: “I have tried to understand them, and I still find it difficult to understand what exactly happened.”

Europe watching closely

Several European capitals are keeping a close eye on the annual meeting of ENTSO-E, the body that brings together the operators of the Old Continent’s electricity grid. The meeting is expected to produce the official report on what happened on April 28.

“Conclusions will emerge tailored to the characteristics of each country, its energy mix, and its grids,” says José Luis Sancha, an energy communicator and professor at Spain’s Higher Technical School of Engineering (ICAI), with a long career at REE.

Before that, however, several issues are already “under discussion,” in Sancha’s words. These include: improving coordination between operators, more clearly defining the responsibilities and penalties for each participant in case of non-compliance, as happened on the day of the major blackout, empowering the system operator in its control management, strengthening the regulator’s oversight of compliance with regulations… and, of course, “improving and expanding interconnections.”

Juan Prieto, director of the new electrical interconnection, at the construction site.FERNANDO DOMINGO-ALDAMA

Juan Prieto, director of the new electrical interconnection, at the construction site.FERNANDO DOMINGO-ALDAMA

González Urquijo advises against speculating “about what would have happened” on April 28 if the interconnections required by the EU had been in place. “What we are clear on,” he concedes, “is that the greater the interconnection capacity, the more robust the grid would be.”

Electricity supply was restored thanks to international interconnections with both France and Morocco. “The greater the volume of interconnections, the greater the speed with which the service is restored,” adds González Urquijo.

Exception made for Spain and Portugal

It seems like another era, but it happened only a few years ago. In June 2022, in the midst of an energy crisis, Spain and Portugal secured an unprecedented exception from normally strict Brussels: the electricity market pricing mechanism would, for once, differ from the rest of Europe in order to remove gas from the equation. The rationale for this leniency was the physical disconnection from the rest of the continent: more than a peninsula, Iberia — it was rightly said — was an insula. Three years later, and after a historic blackout, that remains the case.

Although French authorities publicly claim to be committed to increasing interconnection, the facts tell a different story. This practical refusal has led the Spanish and Portuguese governments to send two letters — one to Paris and one to Brussels — requesting concrete “commitments” to increase electricity flow across the Pyrenees.

“Although not expressed publicly, these delays [by France] are consistent with a French strategy to avoid becoming an electricity transit country: it does not want French consumers to pay for lines that primarily benefit consumers in neighboring countries,” Zachmann explains.

Nor does France want to expose its once all-powerful nuclear power — it has the most reactors in Europe and the second largest in the world — to much more competitive electricity prices: for most hours and days, Iberian wind and photovoltaic power are significantly cheaper than nuclear power. In short, it maintains an artificial competitive advantage against the renewable energy boom.

“The solution could be to require the other partners [Spain and Portugal, which would export more of their surplus, or Germany, the natural destination for cheap Iberian electricity on many days] to contribute to transit costs in France,” explains Zachmann.

Understanding the details of the blackout in Spain and drawing lessons from it has become a concern for all of Europe. This is especially true after the Czech Republic suffered a severe blackout on July 4, albeit for very different reasons, and the Netherlands has had to implement electricity rationing measures to avoid further straining its grid. Even before these events — which took place after the Iberian Peninsula blackout — EU authorities had already launched several parallel investigations. Today, the urgency of learning lessons and putting them into practice is even greater.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Article produced as part of the ChatEurope project, funded by the European Commission.