Ahead of the Ryder Cup in 2016 school teacher Pete Willett – brother of English golfer Danny, who won that year’s Masters tournament – wrote a piece in UK golf magazine National Club Golfer (reprinted in this paper).

Towards the end, he described American fans and their behaviour at Ryder Cup competitions and what the European players must do to win.

That year the Ryder Cup was being staged in Hazeltine National Golf Club in Chaska, Minnesota.

“They need to silence the pudgy, basement-dwelling, irritants, stuffed on cookie dough and pissy beer, pausing between mouthfuls of hotdog so they can scream ‘Baba Booey’ until their jelly faces turn red,” wrote Willett.

“They need to stun the angry, unwashed, Make America Great Again swarm, desperately gripping their concealed-carry compensators and belting out a mini-erection inducing ‘mashed potato,’ hoping to impress their cousin.”

Willett didn’t finish the piece with “only kidding”.

Instead, he pushed harder before the crescendo of a final line describing the American Ryder Cup fans as “those fat, stupid, greedy, classless, bastards”.

It didn’t go down well in the US.

Nor did it hit a sweet note with that year’s European captain, Darren Clarke, who believed the words would be used as motivation by the US team.

In Ryder Cups, more than any other golf tournament, players and patrons staunchly resist surrendering to their better angels.

There was the US navy’s Black Knights flyover during the opening ceremony at the 1991 War on the Shore at Kiawah’s Ocean Course.

Corey Pavin’s Desert Storm baseball cap, boorish fans and the naked expressions of nationalism following the Gulf War jarred horribly.

Following the tournament, bruised feelings and disquiet had replaced the idea that Ryder Cup competition could be contained within the gentlemanly domain in which it was originally imagined.

American Raymond Floyd, a four-time major winner and eight-time Ryder Cup player, called it “a blemish of sorts”.

1991: American supporters fly their national flag during the Ryder Cup at Kiawah Island in South Carolina, USA. Photograph: David Cannon/ Allsport

1991: American supporters fly their national flag during the Ryder Cup at Kiawah Island in South Carolina, USA. Photograph: David Cannon/ Allsport

“I was not for it,” he said. “It was not in the spirit of the Ryder Cup and how it was started and what it was meant to be.”

Bernard Gallacher, the 1991 European captain, said it was a turning point, “and not in a good way”. He cited “hostility” and crowd involvement that affected the outcome of matches.

Now 34 years on from the War on the Shore, it is reasonable to question whether the jingoism will be any different later this month.

At a political level, there have been enough pronouncements and executive orders to expect that relationships between Europe and the US will be simmering.

One act that particularly stands out is the president of the host country threatening to use his military to annex Greenland and make the self-governing territory of Denmark – where European player Rasmus Hojgaard comes from – part of the USA.

Trump accepted his invitation from the PGA Tour to attend with a post on social media. That pleased PGA of America CEO Derek Sprague.

“It’s great to have a sitting president that loves the game of golf, and I think he’ll just help energise the team with his presence there,” he said.

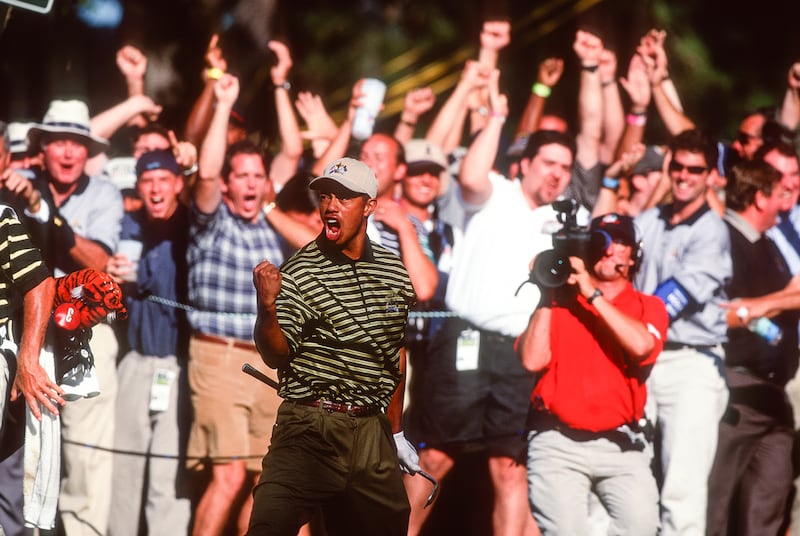

Tiger Woods of the USA in action during the Ryder Cup at The Country Club on September 24th, 1999, in Massachusetts. Photograph: Simon Bruty/ Any Chance

Tiger Woods of the USA in action during the Ryder Cup at The Country Club on September 24th, 1999, in Massachusetts. Photograph: Simon Bruty/ Any Chance

What golf has discovered is that animosity sells, rivalry rocks and bad behaviour may bleed the Ryder Cup of its old-world dignity, but crowds and television buy into conflict.

When Justin Leonard dropped a 50-foot putt at the 17th hole during the Battle of Brookline in 1999, the New York Times described him as running up the green with his fist in the air like “a reveller in search of a party”.

He caught the party. The US team and wives invaded the green and danced.

Tom Lehman, an easy winner over Lee Westwood in the first game of the day treated the gallery to a victory jig over the line of Jose Maria Olazabal, who had a long putt to halve the hole. He missed.

Did the US team care about the brash inconsideration and massive protocol failure? Heck no.

European vice-captain Sam Torrance caught the mood of the European team.

“We’ve all got eyes; we all saw what happened. And it was the most disgusting thing I’ve ever seen on a golf course” he said of Lehman.

On both teams there are neighbours, playing partners and even friends. But the player’s immersion in the patriotic fervour of the Ryder Cup queers the pitch.

They play for what are novel notions for them. They become inflated by community, connection and embrace the unfamiliarity of team-think.

Discarding the selfish, me-first tour posture players adopt week to week, the cold professionals of European golf cozy up to each other in the team room.

That’s the hook of the Ryder Cup, why over three days both teams compete with a fiercely different mindset to what they are used to, one where the next putt taken is for 11 other players, not personal glory, not a pay cheque.

And in Bethpage Black, Farmingdale on September 26th, the raucous New York galleries that once incited Sergio Garcia to deliver them a one-finger salute as they urged him to stop waggling and hit the damn ball, will play their part.

Probably at around ‘Baba Booey’ o’clock.