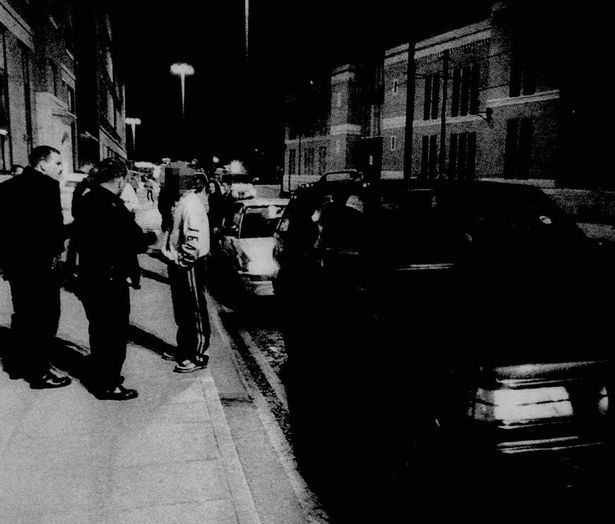

‘There is a cancer in clubland and it’s spreading throughout the city’ A man is questioned by police at a roadblock in Manchester city centre(Image: M.E.N./Mark Waugh)

A man is questioned by police at a roadblock in Manchester city centre(Image: M.E.N./Mark Waugh)

The clubbers driving into town for a night out could be forgiven for thinking they’d taken a wrong turn.

Rolling roadblocks manned by sniffer dogs and armed police in bulletproof vests stretched across the main roads. Some were asked to step out of their cars and body-searched on the pavement.

Known faces were questioned and warned off. But this wasn’t Belfast at the height of the Troubles, it was Manchester in the late 90s.

And the ‘ring of steel’ cops had placed around the city centre was unprecedented in mainland Britain outside of a terrorist attack.

“We aim to show the villains who’s in charge,” a bullish city centre police chief Peter Owen, told the Manchester Evening News. “They’ve got too big for their boots.

Dozens of cars were pulled over(Image: M.E.N./Mark Waugh)

Dozens of cars were pulled over(Image: M.E.N./Mark Waugh)

“Half the people checked were target criminals. This is our town. It doesn’t belong to small, arrogant groups who think they own it.”

A decade after the highs of Madchester and Acid House, a culture of fear and intimidation hung over the city’s club scene. Eight months before the police crackdown, the city’s flagship club The Hacienda had closed suddenly amid debts of £500,000.

But The ‘Hac’ had been living on borrowed time for years. Bosses had voluntarily closed in 1991 for six weeks after it was targeted by gangs. Four years later, an M.E.N. investigation revealed gang bosses had infiltrated the security operation and in 1996 police told owners they had to clamp down on dealing in the club following an undercover investigation into the sale of ecstasy.

Never miss a story with the MEN’s daily Catch Up newsletter – get it in your inbox by signing up here

But then in July 1997 an 18-year-old lad from St Helen’s was left in a coma after being hit over the head with a carjack before being run down by a car outside the front door. It was the final straw.

With the police wanting to revoke its licence, two days later the party was finally over as the legendary club closed its doors for the final time. But the problems weren’t only confined to the Hacienda.

At the same time two other clubs Central Park and Generation X/Code were also under police scrutiny amid efforts to get them closed down. ‘CANCER IN CLUBLAND’ ran the headline in the M.E.N. a few weeks later as the paper ran a double page investigation into the state of the city’s nightlife.

The Hacienda building in 1998(Image: Manchester Evening News)

The Hacienda building in 1998(Image: Manchester Evening News)

“Manchester city centre is booming,” the paper reported. “On an average Saturday night it buzzes with 75,000 people.

“The city council has ridden the wave promoting nightlife as the driving force behind a European-style city. There are now around 350 license premises, 120 more than in 1993. Five thousand people are employed in the night-time scene – and a staggering £250m is spent on entertainment annually.”

But, the bare figures didn’t tell the whole story. Drugs, violence and gangs were wreaking havoc in clubland – and putting the relationship between the venues and police under serious strain.

“There is a cancer in clubland and it’s spreading throughout the city,” one ‘well-respected’ club manager told the M.E.N. “Clubs are being closed because of the activities of perhaps 100 people. These people are eating their way through clubland.”

“Some clubs feel they are scapegoats,” said another. “It’s easier to shut down a club than to get evidence to lock up villains. It’s the job of police to take these people out of society.”

Tragically from there things only got worse. Over a period of 12 months five young men were killed in the city centre while on a night out.

None of the deaths were gang-related, but the bloodshed rocked the city’s night-time economy and some of its most powerful politicians. They included then city council leader Richard Leese who, two years after the IRA bomb, was determined the violence wouldn’t derail the city’s then fledging renaissance.

Court and Crime WhatsApp group HERE

In March 1998 Leese wrote a damning letter to GMP Chief Constable David Wilmot complaining of the ‘rampant lawlessness’ in the city that police seemed ‘either unable or unwilling’ to combat. The problems of ‘thugs and gangsters seem to have escalated, spreading to other areas of business activity within the city centre,’ he added. “And now they are seriously undermining business confidence so vital for the city’s regeneration.”

The letter was leaked to the M.E.N. who splashed its contents across the front page. The climate of fear and intimidation threatening Manchester’s renowned nightlife was now well-documented public knowledge.

Manchester council leader Richard Leese pictured in 1996

Manchester council leader Richard Leese pictured in 1996

Police were forced into action. Operation Sulu, as it was dubbed, was launched.

Over two weekends in April 1998, rolling roadblocks were put in place, patrols stepped up and club visits increased. Almost 100 cars were stopped and 170 people questioned as they made they way into town.

“It’s a question of getting the balance right,” said Sgt Jan Brown who helped organise the operation. “It’s clear people want a high profile presence – except those who want to spoil the party of course.”

It was an extraordinary response to a deeply troubling problem. And not everyone was happy about it.

A sniffer dog searches a car during Operation Sulu(Image: M.E.N./Mark Waugh)

A sniffer dog searches a car during Operation Sulu(Image: M.E.N./Mark Waugh)

As an M.E.N. reporter and photographer watched on, a ‘notorious hardman’ whose personalised Mercedes was waved over by police at a roadblock on Aytoun Street, was questioned. Dressed in tee-shirt and baggy shorts, he gave his occupation as ‘unemployed’ before driving away and videoing police with a handheld camcorder.

Later four arrests were made drugs were found in a black Ford, in which ‘probably the city’s most notorious heavyweight’ had been seen.

Coun Pat Karney, then chairman of the council’s city centre committee, had publicly backed the crackdown – and received a sinister threat for his vocal support.

“I had a personal threat from a particular gang leader,” he told journalist Peter Walsh. “He passed a message to somebody that works for me in the town hall saying that they were finding out where I lived.

“It’s an indication of how far this cancer of fear has spread where they can put indirect threats to elected people like myself. Once that happens and if elected people get them we might as well give up and go home.”