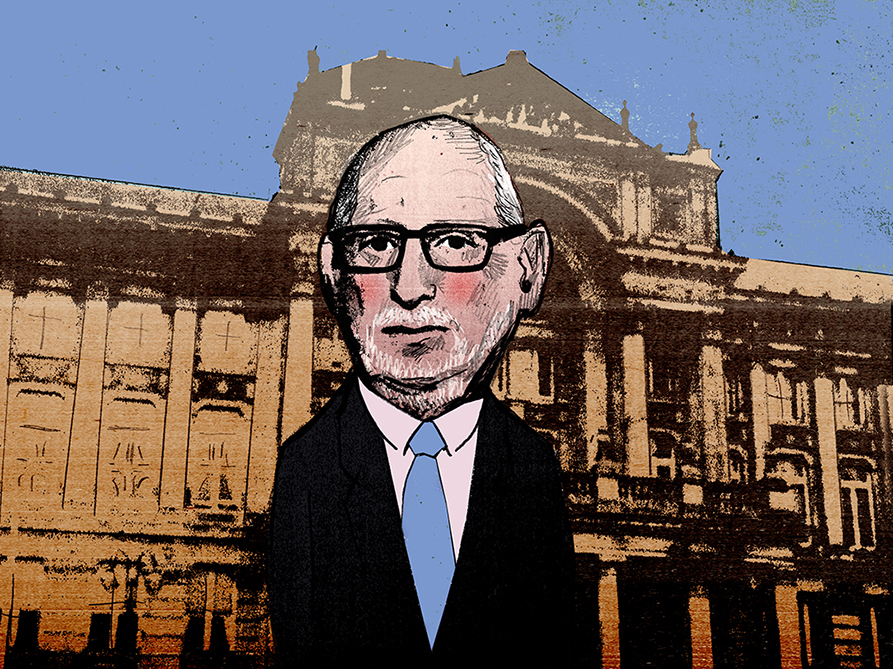

As the government’s long-time fixer of broken and bust councils, Max Caller would like to be known as the “poster boy for best value”. Unfortunately for him, he is less generously referred to across the world of local government as “Max the Axe”.

He won the moniker near the start of his five-decade career. In the mid-eighties, Caller was installed at Barnet council and tasked with, among other things, resolving a dispute set off by the council’s plan to introduce wheeled bins. Caller fixed a “disastrous” landfill contract, cut the costs of bin collection and resolved the dispute with the workers. His colleagues were thoroughly “impressed”, and crafted him a celebratory badge of an axe. Resolving the dispute, Caller told me, was a “proper negotiation”. Key to that, he feels, was that the stirking workers from the GMB union “respected” his straightforwardness. He recounted, “It was clear that I was going to modernise the service. No one had had the steadfastness to actually make it quite clear that this was what the council was going to do – and the workforce were impressed with that.”

Caller’s career in local government career was bookended by another dispute over refuse. “History keeps repeating itself,” Caller noted when we spoke a few weeks after he stepped down as lead commissioner of Birmingham City Council, to retire for the third time. Birmingham’s bin strikes are now in their seventh month, and its picketing workforce has seen tons of rubbish line England’s second city. Caller, who had been tasked with leading £300m of cost savings following the council’s bankruptcy in 2023, came to be seen as the villain of the strikes.

Sharon Graham, the doggedly worker-oriented general secretary of Unite, has waged a very public war with Caller and his team of commissioners. She has criticised their fees (“an eye-watering £1,200 a day”), accused them of “sabotaging” negotiations and branded the council’s service reforms as “fire-and-rehire”. When I asked him about the charges, Caller projected indifference: “I’m not doing a tit-for-tat with Sharon. She does what she does; nothing to do with me… I’m not responding to it. Never have.” His composure wavered when I mentioned that I had spoken to Graham prior to our discussion. He snapped: “You got a word in edgeways, did you?!”

A key part of the reforms in Birmingham is about, the official line goes, avoiding an equal pay claim from female refuse workers. The council had already paid out £1.1bn from previous equal pay claims. Unequal pay between the sexes has “been a running sore and a stain on local government’s conscience,” Caller said. Graham agrees, but insisted that in redressing pay, “it is not the case that men should be pushed down… Women should be pushed up”. That calculation is not compatible with Caller’s agenda: “The suggestions that the national union makes can’t ever be afforded… It’s easy to say, ‘Oh, well, you can level everybody else[‘s pay] up’. We all know where the money is for that.”

There are few people more authoritative on issues of local government than Caller. His very first council job, which he got in 1972, involved inspecting London’s sewers. His later, more senior, jobs have seen him repair disaffected councils of Slough, Liverpool and Tower Hamlets. He has already received two offers that would bring him out of retirement once again – for the fourth time. “People have come along and said, ‘We don’t believe that you’re going to really retire. Can you come and talk to us after the summer?’ And I will, but it’ll have to be seriously interesting.”

But he made it clear that he would not be at the forefront of another full-on council restoration. “I will never do something as intense as leading an intervention ever again, because that really, really takes it out of you,” Caller confided. “It’s not a job for someone who thinks that you can’t do it 24 hours a day.”

Subscribe to The New Statesman today from only £8.99 per month

Some argue leading councils was made impossible by austerity. Central government funding to local authorities declined by 40 per cent in real-terms between 2009/10 and 2019/2020. I asked if Caller had a view on Osborne’s impact on local government. “Yes, and it’s my view,” he replied, unwilling to disclose any stance that might burn bridges in his lucrative line of work. “It’s not for me to have a [public] view! I’m not elected…”

He is more willing to blame a failure of localised planning. Perhaps they did austerity the wrong way round. Many “cut their resources in the centre for short-term savings,” Caller said. Cutting central operations “to the bone” prohibits councils from having the personnel or expertise to “make the savings that would have, over time, delivered better services for less money… That sort of approach has been the downfall of quite a number of authorities.” Though he acknowledges: “The [current] cost pressures are huge on all parts of local government.”

For many in Birmingham, the new cuts to frontline services Caller and the council have advanced have gone too far, too quickly. This year, as well as a 7.49 per cent increase in council tax, there were cuts of £43m from adult social care, £40m from children’s social care, £20m from various “city operations” and £18m from housing budgets. One man with severe disabilities took the council to court over its refusal to reduce parts of his adult social care charges. “Yes, people have gone to court – but they haven’t won,” Caller remarked. Despite the financial mire the authority finds itself in, Caller believes that councillor John Cotton, the Labour leader of Birmingham City Council, is “taking hard, but proper political decisions, and they will come out of it”.

Though he sees the cuts in Birmingham as a necessarily evil in the service of the greater good, Caller acknowledges “that people are concerned about services”. He told me, “I want [the] council to do the best they can with the resources that they’ve got, because we know that people need their local authorities.” He added: “The task of commissioners is always to help the council get back to doing what it’s supposed to do: deliver services, lead the community, create opportunities and senses of place. Help people get those things without having to worry about whether or not their bin is actually going to be collected.”

But whether it is bins, opportunity or sense of place, the consensus seems to be that the current system of local government simply isn’t working anymore. Perhaps surprisingly, Caller agrees. He points to an ongoing review by the Welsh government, over how best to reshape municipal governance. “The Welsh local government doesn’t yet seem to have a set of priorities that can be afforded… because if Westminster doesn’t give Wales any more money… then something has to change.” Caller added: “It may be that English local government needs to do a similar sort of thing.”

When it comes to local government, Labour has spoken the language of devolution; complete destruction and reform has never been on the agenda. Caller has seemingly called time – cautiously – on the current structures. “I’ve been around in local government for such a long time. There are things done now that we didn’t do then; and there are things that we don’t do now that were done in the 1970s,” he said. “Local government shape-shifts [over time]… so it may be that’s what we’ve got to do. We’ve got to say, ‘What is local governments meant to be about?’, and then work out what to do.” Time will tell.

[See also: Paul Nowak: “I think Nigel Farage is taking the piss”]

Content from our partners