From forgotten statues to mysterious caves, Merseyside is full of hidden historic sites you’ve probably walked past without noticing Rare ‘Penfold’ post box on Ashville Road, Birkenhead(Image: Andrew Teebay Liverpool Echo)

Rare ‘Penfold’ post box on Ashville Road, Birkenhead(Image: Andrew Teebay Liverpool Echo)

Merseyside is famous for its music, football, and waterfront – but beyond the well-trodden tourist spots lies a wealth of history that most of us pass by without a second thought. Tucked into quiet streets, hidden corners, and overlooked landmarks are relics of the past that tell stories of the region’s industrial, maritime, and social heritage.

From weather-worn statues and forgotten police cells to mosaic ships, haunted caves, and 16th century courtrooms, these sites offer a glimpse into a side of Merseyside that even many locals don’t know exists. Each carries its own unique tale, waiting to be discovered by the curious explorer.

Here are 11 historic and little-known sites scattered across the county, each with a story that could surprise, intrigue, or even spook you.

Kirkdale dock shunter A Ruston & Hornsby locomotive engine on the corner of Derby Road and Bankfield Street(Image: Conaill Corner/Liverpool Echo)

A Ruston & Hornsby locomotive engine on the corner of Derby Road and Bankfield Street(Image: Conaill Corner/Liverpool Echo)

Coated in rusted green paint and a little graffiti, it looks like an abandoned relic, but this dock shunter isn’t just a piece of scrap metal – it’s a tribute and a symbol of the area’s historic importance.

The engine, on the corner of Derby Road and Bankfield Street in Kirkdale, is a Ruston & Hornsby model – serial number RH 224347 to be precise. But unlike the steam and diesel workhorses that once bustled along the dock lines, this particular engine never turned a wheel in Liverpool’s working port.

Instead, it was brought here in 1998, as a symbolic gesture to mark the regeneration of the area.

Its arrival coincided with the ambitious ‘Atlantic Avenue’ scheme, during which the Merseyside Development Corporation transformed the A565. The engine was installed as a nod to Liverpool’s industrial heritage, even if it never actually took part in it.

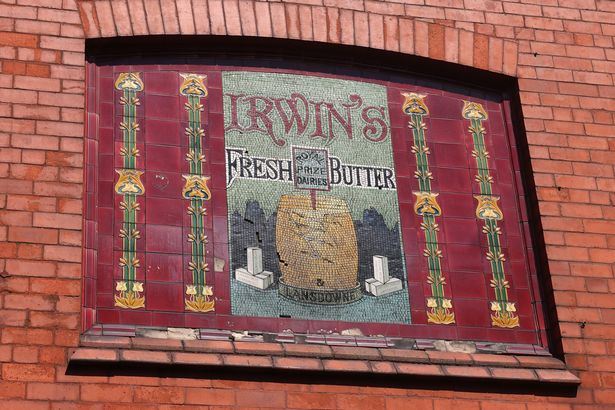

Irwin’s mural The mural reads “IRWIN’S FRESH BUTTER, ROYAL PRIZE DAIRIES”(Image: Liverpool Echo)

The mural reads “IRWIN’S FRESH BUTTER, ROYAL PRIZE DAIRIES”(Image: Liverpool Echo)

Tucked behind St Barnabas Church on Allerton Road, nestled on the side wall of what is now an estate agency, lies a reminder of a forgotten Liverpool success story.

It’s easy to miss – many walk past it daily – but this tiled mural, advertising prize-winning butter from Irwin’s, is more than a ghost sign. It’s one of the last surviving traces of a homegrown grocery empire that once rivalled the biggest names on the high street.

The mural, splendidly preserved in deep red tiles, once marked one of more than 200 stores in a retail chain founded by Irish immigrant John Irwin.

Irwin opened his first shop on Westminster Road in 1874 and, by the 1950s, Irwin’s had become a fixture across Liverpool and beyond. Known for their distinctive red livery, the stores were often referred to in the firm’s advertising as “The Ruby Red Stores’” Mosaics, like seen on Allerton Road, adorned the outer walls of several shops.

Penfold post box Rare ‘Penfold’ post box on Ashville Road, Birkenhead(Image: Andrew Teebay Liverpool Echo)

Rare ‘Penfold’ post box on Ashville Road, Birkenhead(Image: Andrew Teebay Liverpool Echo)

A rare piece of Victorian history can still be seen in Birkenhead – and many people pass by it every day without realising how special it is. The red post box on Ashville Road, near the junction with Cavendish Road is one of the few surviving “Penfold” post boxes in the UK.

It dates back to the 1860s and is named after its designer, John Wornham Penfold. Only around 150 original Penfold boxes remain in Britain today, and just 20 of those are the earliest kind, known as “Mark 1”.

The Ashville Road box is one of them.

What makes the Penfold design so unique is its shape. Instead of the round pillar boxes we’re used to seeing today, Penfold boxes are hexagonal – meaning they have six sides. They also have a pointed top, decorated with patterns of leaves and a small acorn-shaped finial.

The box was made by Cochrane, Grove & Co in Dudley and would have been placed on the street sometime between 1866 and 1871. It is now Grade II listed, which means it’s protected as a structure of special interest.

Although the box is no longer in perfect condition, it’s still in good shape for its age. It continues to be used for posting letters, just as it was over 150 years ago.

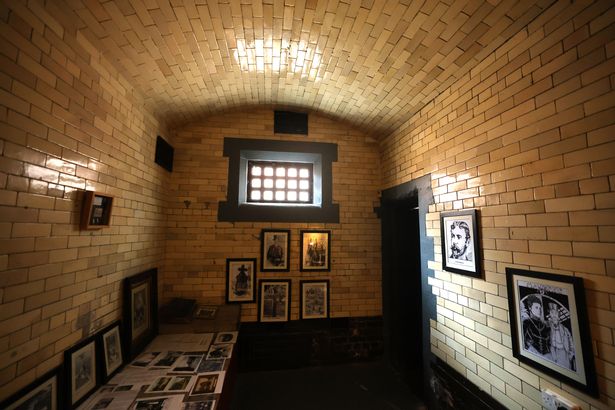

Florence Maybrick’s police cell Florence Maybrick’s police cell on Lark Lane(Image: Liverpool Echo)

Florence Maybrick’s police cell on Lark Lane(Image: Liverpool Echo)

It’s probably Britain’s most infamous unsolved murder case: who was Jack the Ripper? Some think he was born and bred right here on Merseyside, believing the serial killer to be none other than James Maybrick, a wealthy Liverpool cotton-broker.

A diary discovered in 1992 described how Maybrick went on a murderous rampage after seeing his wife, Florence, with her lover. And while many experts have dismissed the diary as a hoax, James wasn’t the only person in his family thought to be a murderer. According to the British courts, his wife Florence Maybrick’s transgressions went far beyond infidelity as she was eventually convicted of murdering her husband in one of the most well-documented trials of the 19th century.

James had died in May 1889 and an inquest into his death pointed to arsenic as being the most likely the cause of his demise. Florence was found guilty of his murder later that year.

The then-27-year-old was convicted at St George’s Hall in a trial that made headlines across the world after she confessed – not to murder, but only to adultery. She was sentenced to death, a penalty which was later reduced to life imprisonment.

People can actually visit the south Liverpool police cell where she was held after her arrest. It lies within The Old Police Station on Lark Lane, which is now a community centre. Many of the thousands of people who pass the building every day may be unaware of its historic significance.

Titanic sculpture The Titanic on Park Road(Image: Andrew Teebay Liverpool Echo)

The Titanic on Park Road(Image: Andrew Teebay Liverpool Echo)

On Park Road in Liverpool 8, there stands an 11-foot-long mosaic replica of the RMS Titanic – unmissable by the thousands of cars passing it every day. Unveiled in 2012 as the Flat Iron development’s centrepiece, the sculpture pays tribute to Liverpool’s deep connection with the ill-fated liner.

The Titanic mosaic was commissioned as part of the Love L8 regeneration project, designed to breathe new life into the Park Road neighbourhood. Artist Alan Murray was commissioned to create the ship model, and the Titanic theme was chosen to commemorate the city’s maritime legacy and to mark 100 years since disaster struck the ship in April 1912.

In 2020, the Titanic model took on fresh meaning with a new look. Faced with the COVID‑19 pandemic, the mosaic was coated in rainbow colours while a flag thanking NHS and key workers was also added.

Fruit Exchange auction halls Traders would bid for fruit here(Image: Andrew Teebay Liverpool Echo)

Traders would bid for fruit here(Image: Andrew Teebay Liverpool Echo)

The historic Fruit Exchange building on Victoria Street in Liverpool city centre was built in 1888 and first operated as a railway goods depot for the London and North Western Railway.

In 1923, it was converted into a fruit exchange by James B. Hutchins. Becoming the main trading point for fruit in the city, hundreds would cram into the auction halls to bid on produce freshly arrived in Liverpool from around the world.

The office and exchange hall parts of the building have been left empty for many years and featured in the ECHO’s ‘Stop the Rot’ campaign. Plans to convert the front section of the building into an 81-bedroom hotel were approved by Liverpool City Council in 2024.

The part of the building that backs onto Mathew Street originally housed the famous Eric’s Club, and later the Rubber Soul bar. The company which now owns Eric’s, JSM, has recently installed a glass window in the ceiling of the bar, allowing guests to look up at the old exchange halls and catch a glimpse of the past.

The Five Lamps The Five Lamps in Waterloo

The Five Lamps in Waterloo

Thousands of people pass the Five Lamps in Waterloo daily, but few will give the impressive monument a second glance. The historical landmark on Crosby Road South has stood watching over the road for more than 100 years, and it has a poignant meaning.

Unveiled in 1921, the Five Lamps is a monument which carries a winged Greek goddess Victory, who stands on a small globe, holding a laurel wreath in her right hand and a palm branch in her left. The statue is surrounded by three lampposts, one with a single lamp and the other two with two lamps – hence its name.

A war memorial, it lists the names of local servicemen and women who lost their lives during both world wars. It reads: “OUR GLORIOUS DEAD WHO FELL IN THE GREAT WAR, 1914-1919. THEIR NAME LIVETH FOR EVERMORE. AND THOSE WHO FOLLOWED, 1939-1945, WE WILL REMEMBER THEM.”

While there were five lamps on Crosby Road before the war memorial was built, they were all attached to a single post. They were rearranged to surround the monument when it was erected, with each lamp representing the years during which WWI was fought.

The Five Lamps is placed at the border of Waterloo and Seaforth, making it an unofficial marker of the boundary between the two areas.

Manor Court House Manor Court House in West Derby Village(Image: Liverpool Echo)

Manor Court House in West Derby Village(Image: Liverpool Echo)

In the historic village of West Derby stands a modest sandstone building with mullioned windows, a studded oak door, and centuries of legal heritage. Manor Court House is a rare and precious remnant of Elizabethan England – believed to be the only surviving freestanding court building from the 16th century. Though unassuming in size, its role in Liverpool’s early justice system was monumental.

West Derby Village is steeped in history which dates back as far as 1086 when it was first mentioned in the Domesday Book. However, it was during the Victorian period that the village underwent a real transformation and was largely rebuilt by the 4th Earl of Sefton, William Philip Molyneux, whose family lived in Croxteth Hall for generations.

The current building dates to 1586, when Queen Elizabeth I, as Lady of the Duchy of Lancaster, ordered a new courthouse to be constructed following reports that the old one had fallen into disrepair. A royal warrant was granted specifying the size and materials, and £40 – an enormous sum at the time – was allocated for its construction.

Back then, the courthouse was used to issue fines for offences like not attending church or keeping a pig without a ring in its nose. If you didn’t pay the fine you could be put in the stocks for up to six hours.

Over 400 years later, the structure still stands.

Cannibal caves Inside Crank Caverns

Inside Crank Caverns

In the countryside outside St Helens lies a cave system shrouded in mystery and myth, where children are said to have been murdered by “cannibalistic dwarves,” and where persecuted Catholics would apparently worship in secret during the Reformation.

In later years, the complex network of caves and tunnels is believed to have been used as a game reserve and also an ammunition storage facility during WWII. Today, due to its instability and health and safety concerns, it is not officially open to the public. However, the exterior of the site can still be seen via a nearby footpath.

Crank Caverns in Crank, St Helens, has been the subject of dark folktales and myths for centuries. Formerly Rainford Delph Quarry, the site’s origins can be traced back to the 18th century.

The most well known legend associated with the caverns is that, during the Reformation, local Catholics being persecuted by King Henry VIII (1491–1547) took shelter and conducted secret mass there – but mining on the quarry only began in about 1730.

There are numerous stories of people going missing from the caves. It’s rumoured that “cannibalistic dwarves” once inhabited the tunnels. In the late 18th century, four children reportedly decided to explore the sandstone caverns and vanished. One child survived and told a story about small old men with beards who killed his three friends and chased him.

Axe-wielding watchman The figure atop what was once the Dominion pub(Image: Andrew Teebay Liverpool Echo)

The figure atop what was once the Dominion pub(Image: Andrew Teebay Liverpool Echo)

High above Bankfield Street in Bootle, a solitary statue keeps watch over Canada Dock. Axe in hand, dog by his side, the weather-worn figure has stood for decades atop what was once the Dominion pub – now long closed and largely forgotten. But the statue remains, a strange and stubborn symbol of the area’s maritime past, and of a mystery that’s never quite been solved.

The Dominion stood at the corner of Bankfield Street and Regent Road, right at the heart of Liverpool’s historic trade with North America. Its name is thought to come from the Dominion Line – a transatlantic shipping company that ferried goods and people between Liverpool and Canada from the late 19th century. The line played a key role in the emigration of thousands of hopefuls seeking new lives across the Atlantic.

By the 1850s, Liverpool was receiving millions of cubic metres of timber from Canadian ports every year. Canada Dock, opened in 1859 under the famed dock engineer Jesse Hartley, became a central hub for the trade in wood, wheat, and fish.

It’s easy to imagine the axe-wielding figure on the Dominion’s roof as a tribute to that trade – a tough, rugged frontiersman capturing the spirit of the times. But who exactly is he?

There’s a few theories. Some, like writer Mike Keating in ‘Secret Liverpool – An Unusual Guide,’ suggest the statue is a symbolic nod to the timber industry. In the book, he writes: “As the pub carries the name of the shipping line and the character on the roof is gripping an axe, it is fair to assume that this is in celebration of the timber trade, but not everyone agrees.

“Ruth Gregory (on www.picturesofengland.com) suggests it may show the mythical American giant Paul Bunyan, who has at least eight roadside statues to his name across the northern forests of Minnesota, Wisconsin and Michigan.

“On the other hand, Jimmy Conelly, who works at Terry’s Timber Yard and used to drink in the pub, assures the character is a cotton picker.”

Battlefield golf course Brackenwood Golf Course, in Bebington, pictured before it closed

Brackenwood Golf Course, in Bebington, pictured before it closed

Brackenwood Golf Course in Bebington, Wirral, has stood empty since its closure in 2022. Once alive with the thwack of drives and the chatter of weekend players, its fairways now lie silent. Yet some historians believe the ground hides echoes of a much noisier, bloodier past – the site of the Battle of Brunanburh in 937.

For centuries, historians have argued over where Brunanburh took place. Some point to Yorkshire, others to Lancashire or even Northamptonshire. But a growing body of research suggests this patch of Merseyside turf could have been where England was born.

The battle pitted King Athelstan, grandson of Alfred the Great, against a formidable alliance of Norse, Irish and Celtic kings led by Anlaf of Dublin and Constantine of Alba. Determined to halt Anglo-Saxon expansion, their armies marched south, meeting Athelstan’s forces on a patch of land that many now believe was in Bebington.

The fighting was ferocious. The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle records: “Never yet on this island has there been a greater slaughter. When it was over Athelstan and his brother Edmund returned to Wessex, leaving behind corpses for the dark black-coated raven, horny-beaked, to enjoy.”

It was not just a clash of armies but of destinies: the outcome would determine whether the warring kingdoms became a united England.

While it’s not certain where the battle was fought, the most popular theory is that it occurred at Brackenwood. Bromborough, just a short walk from the course, which held the Norse spelling until the 18th century, and the Wirral was a Norse settlement, offering the perfect landing spot for Dublin’s Viking fleets.