Perhaps it’s the last ten years of conversation I’ve had with the artist herself, ten years of building intimacy in fragments and flows, that inspire me to take Kim’s own words, from the tender and beautifully frank new epilogue she has written for the anniversary edition of Girl in a Band, and to go ahead and reformulate those words into a stanza that lets sky through the lines of her self-assessment:

Article continues after advertisement

I’m an introvert

and yet I chase this feeling

which can only be conjured

with the mass of people in the dark

I’ve learned so much from Kim Gordon up close that I can’t help but mimic what she does in order to talk about her. By phone, by text, in person, among others or just us, in a car or at the movies, in unspoken glances, in the lowest register of telepathic reverberation, I am always listening for Kim’s reduction of reality to essence. She locates the thing within the thing, the part that is hidden under the literal, that which might speak multitudes in monosyllables.

Like Iggy Pop overhearing the guttural patois of teenagers in a doughnut shop and later coming up with the lyrics of “No Fun,” Kim takes from the ever-changing world and spits out shimmery coins. She surfs the inscrutable. (She also surfs for real, gets walloped by waves, stands back up.) She’s interested in aspects of life that some of us find increasingly and maddeningly weird, weirdly difficult to grasp. Instead of turning away from the textures of tomorrow, Kim turns toward. “It’s . . . abrasive,” she said to me in warning, when describing The Collective, an album that would go on to hit the big time, even as it’s uncompromising, loud and rude and mesmerically catchy, the sound of now.

Once, upon returning home to L.A. from New York City, her report to me of the mood there: “People are acting out.” It’s the kind of thing Andy Warhol would have said, but she didn’t get it from him. She has her own gift for cutting to the chase, summing up the contemporary, or turning it on its side. People are acting out. Still, Warhol was a critical early reference. One of Kim’s first artworks was a pair of boots she asked him to sign at his art opening in Venice, California. The boots were made of white canvas. In bearing Warhol’s signature, they effectively became a painting.

Article continues after advertisement

Kim’s own paintings of the last decade or so are often messages that function as image, scrawled words whose meaning is more like anonymous graffiti, the unconscious of the world revealed on the surface as a two-word slogan: “Dude War,” “Product Owner,” “Larry Gagosian.” (Readers of this memoir will learn that Larry is not just top Doberman among art dealers but was once-upon-a-time hustling art books on a Westwood sidewalk, as well as “schlocky, mass-produced prints” in “cheap, ugly metal frames” that he hired Kim, just out of high school, to assemble.)

Hourly employee, actress, muse—even when she’s cast in someone else’s plot, Kim brings her gift for sly intervention. In Albert Oehlen’s movie Bad Painter, she’s a documentary filmmaker who acts more like a stern psychoanalyst, with German actor Udo Kier as her patient, a painter with a self-indulgent streak. She conjures the therapeutic structure by paring it down to an analyst’s unforgiving stare. Richard Prince, in a video recording of his deposition for a copyright infringement lawsuit, tells the plaintiff’s attorneys that he’ll share a little-known secret: long ago he taught Kim Gordon to play guitar. It’s a joke she’s in on, even before I tell her about it, after watching the deposition. She and Richard, as she relays in this book, have been friends since the late seventies, when he was a mysterious loner who walked into the Annina Nosei Gallery, where she was working, with a portfolio of re-photographed watch advertisements, and Kim teased him for having mounted them in what she immediately recognized as Larry Gagosian’s crappy aluminum frames.

People tend to marinate in their own self-mythology. Kim does not.

People tend to marinate in their own self-mythology. Kim does not. At a film screening we attended at a Santa Monica high school auditorium, she said quickly, flatly, as we chose our seats, “I went here.” At a theater on Wilshire, as we exited, “This is where I saw my first Godard movie.” In Picture Window, a 2022 film directed by Kim and Manuela Dalle, she’s in her L.A. house made strange and ersatz, doubling as a set, as she plays herself also made strange, almost an automaton. She naps, the camera static on her face; wakes; starts to move through a series of beauty rituals and domestic chores, a latter-day Jeanne Dielman.

She’s in a silky short robe, and like the real Kim, who is playing this zombie Kim, her feminine poise is blended with a certain androgyny: the slim muscular limbs, a calm unself-consciousness. She has the averted gaze of an introvert, a private person at whom others are compelled to stare. (It’s this sense of a privacy, more than her features, the blond hair, that makes her and Kurt Cobain seem like siblings.) Sleepwalking Kim has a live electric guitar front-slung, the instrument creating sound, buzz, distortion, as it bumps against the bathtub she cleans. She moves as if unaware of the guitar, which gives electric feedback to the act of scouring, of vacuuming, of setting the table for lunch. Gives sound to the air in the rooms where Kim, and her double, live. Gives sound to solitude, a room tone her zombie double conjures.

“I chase this feeling” is her telling us what drives her to be onstage. To move into a dream-space in front of strangers, “the mass of people there in the dark.” Back in 1991 at the Cow Palace in San Francisco, when Sonic Youth opened for Neil Young, I was among that mass. “People pay money to see others believe in themselves,” Kim herself once wrote. That’s what I’d done. Now that I know her up close, decades later, I can say that when she’s standing in front of the monitors, she’s both someone else, transformed, and then again her truest self, tapping distortion pedals in her kitten-heeled boots, her drugstore fishnets, inlaid with rhinestones catching the lights. (She long ago realized, as she describes in these pages, that “if you wore sexier clothes, you could sell dissonant music more easily.”) Up there, she’s a million miles away, and yet unable to hide—from other people, and from herself.

Article continues after advertisement

Distance is key to the power of her performance. But it’s key to her offstage life as well. The shy need their space and they carry it around them, a kind of ethereal buffer zone, or maybe a lens, that lets the truth stream through and come into focus. The shy opt for space between words, for stretches of silence. When they do decide to speak, it’s because they have something to say.

___________________________

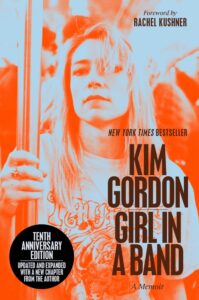

Excerpted from Girl in a Band (10th Anniversary Edition) by Kim Gordon. Copyright © 2015 by Kim Gordon. Foreword copyright © 2025 by Rachel Kushner. Reprinted by permission courtesy of Dey Street Books, an imprint of William Morrow/HarperCollins Publishers

Article continues after advertisement