“When [his mother] Judy dropped him off at Murphy’s Caulfield stables in the mid ’70s, Andrew was officially the smallest and lightest apprentice in Victoria,” Green told a small gathering of family and friends in Federation Chapel at Lilydale Memorial Park.

“For the next six or seven years, we slept in adjacent beds in the kids’ dorm.

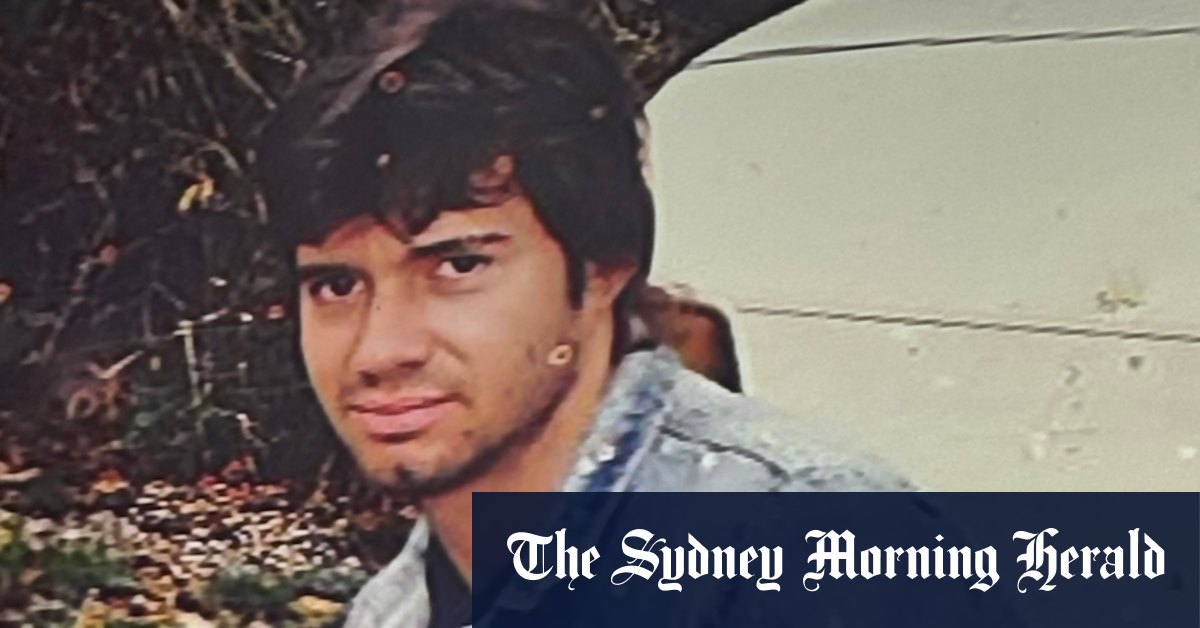

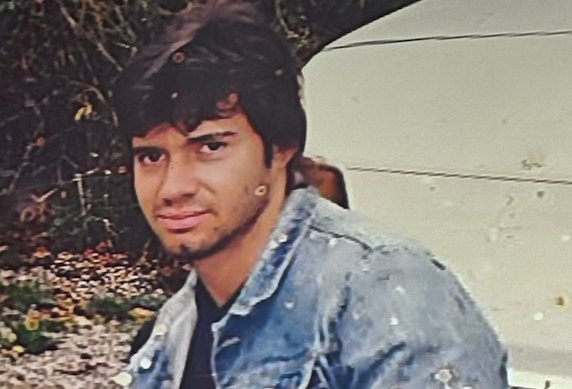

A young Andrew Vine had to give up being a jockey in the early 1980s after breaking his pelvis in a track accident.

“We ate our meals together, we worked and rode horses alongside each other, and we gave each other unconditional support through the many challenges of that brutal and chaotic environment.”

Vine and Green both entered the stable environment as 14-year-olds, having been granted early exemption from the education department. It was no place for a teenage boy.

They were at the mercy of sadistic and perverted stable staff and because they had been indentured as apprentices by the state’s governing body of racing, felt like they had little choice but to abide.

Their treatment was kept as a dark secret for 30 years; they battled drug and alcohol addictions, and their pain was not aired in public until the 2008 “Jockey Ritual Trial” in the County Court.

Vine and Green were key prosecution witnesses in a case that led to two Caulfield stable hands – John Finlayson and John William Honeysett – being convicted of indecent assault during the 1970s.

“I’ll never forget Andrew’s unwavering supporting testimony that he gave under extreme pressure from a pair of rabid defence lawyers,” Green said.

“He was staunch and tough, and he didn’t give an inch.”

Loading

Until Vine’s death, he hoped for restitution and accountability. He was to be part of a civil case against Victoria Racing Club, which was racing’s governing body until 2001, seeking redress for historical pain and suffering.

Despite his promise to Green to stay alive, he could not reverse his slide into ailing health, and died at home. Vine never had his day in court.

Instead, family and friends were left on Friday to make sense of the 64-year-old’s tumultuous life.

Vine’s first winner made headlines. He booted home 140-1 shot Tobazari at Caulfield in the late 1970s as an apprentice. But his riding career ended abruptly when he broke his pelvis during a training accident.

He entered the workforce and started a family in the late 1980s – taking in partner Margaret’s children Mark and Tara before having a son of their own, Jesse, in 1992.

But the injuries kept coming.

Vine broke his neck in a workplace accident around the time his son was born, and eight years later he was clipped by a passing car while helping an elderly woman change a tyre.

“He didn’t call an ambulance,” his son Jesse said. “He just walked it off, went home and laid on the floor because he insisted it was less painful than laying in bed.

“A few surgeries, and a few years later, his back was still no good.

“He definitely didn’t do himself any favours, not getting any details of anyone that was there, or any witnesses. So he was sort of left to fend for himself.

“But that was Andrew. He never wanted to make a fuss.”

Former apprentice jockey Andrew Vine was described as a ‘rough diamond’ at his funeral service.

Vine and Margaret separated in 1996, but became best friends. He would later become a “stepfather” to her fourth child, Mia, whose own father died in 2007 when she was four and a half years old.

“Mia and I moved into Andrew’s, and he looked after myself and Mia like she was his own,” Margaret said.

Vine was described on Friday as a “cool dad” and a “bit of a rough diamond”.

He had a “biker period”, worked on cars in his backyard, enjoyed a punt and didn’t mind a go on the pokies. His son even compared him to a hard-living rocker.

“When Ozzy Osborne died at the age of 76, I thought, ‘I reckon Dad’s got another good 10 years left at least’. But, yeah, apparently not, Dad,” Jesse said.

But above all, Green said, Vine was “decent, kind, generous and unflinchingly loyal”.

“He was a proud and devoted father to Jesse, a committed partner to Margaret, a loving son, brother and uncle,” Green said.

“He truly loved animals, and we all know that animal lovers are the very best of people. For me, Andrew is my dearest friend. In many ways, my only true friend, and I’ll never, ever forget him.”

Green has now farewelled all three of his former roommates from their horrific Caulfield apprentice days.

Three years ago, Vine was one of more than a hundred witnesses, not all of them victims, who took part in a review of historic abuse within the Victorian racing industry.

The Office of the Racing Integrity Commissioner released a 78-page paper in September 2023 calling on racing’s three codes – gallops, harness and greyhounds – to draw on “best practice from other sports and industries” to create a redress scheme for victims within 12 months.

Racing Victoria announced a “restorative engagement program” for “impacted individuals” last month. It is open for submissions for six months from September 1.

There is no mention of financial compensation or accountability. Instead, the two main components will be access to an individual story-telling meeting with an RV representative, designed to be “healing for participants”, as well as access to free counselling (up to 10 sessions) and free psychiatric care (up to four sessions).

Racing Victoria said that “participation in the program does not replace other legal processes or avenues that may be available to impacted individuals”.