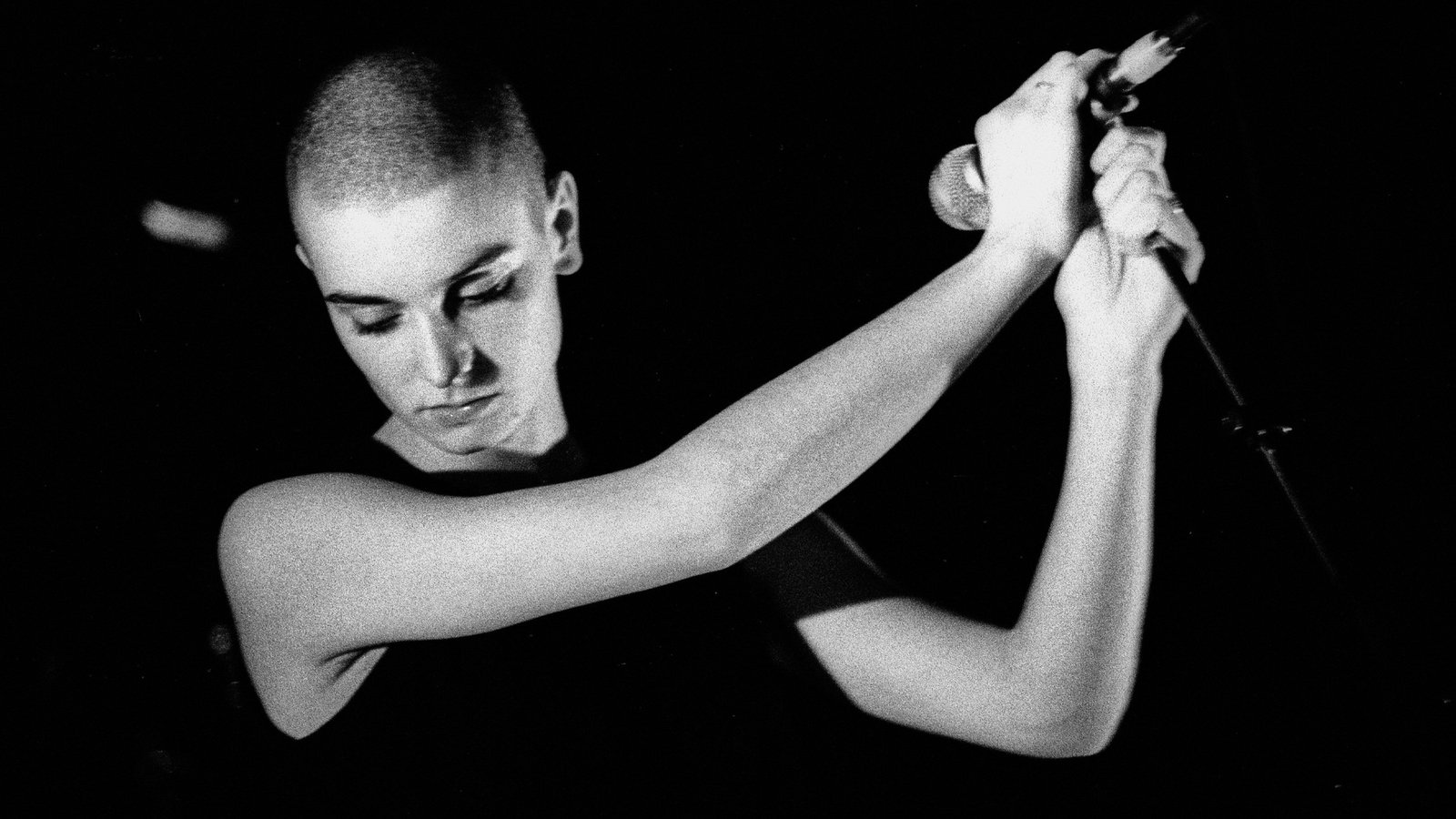

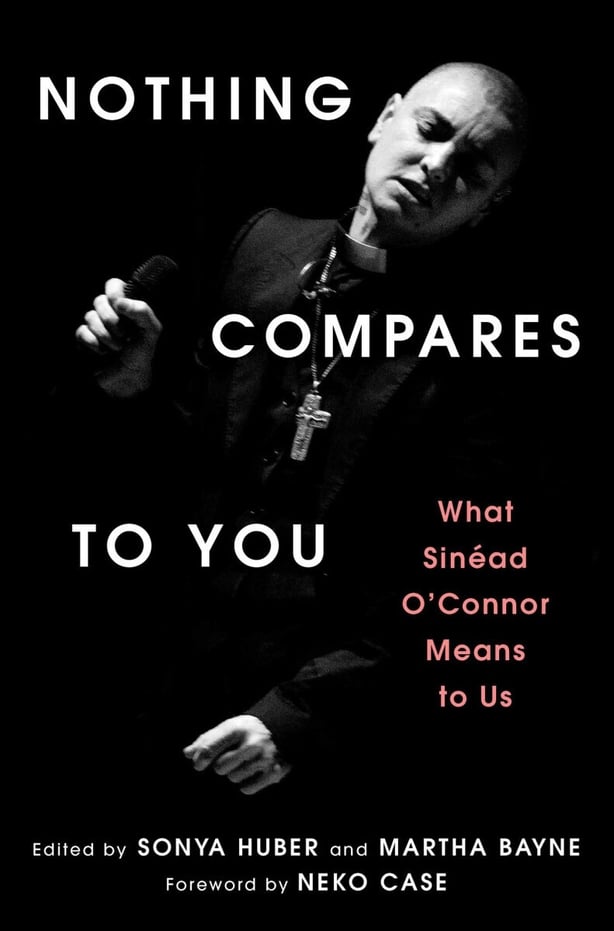

Via The Journal Of Music: A new book, Nothing Compares to You: What Sinéad O’Connor Means to Us, edited by Sonya Huber and Martha Bayne, brings together 25 essays inspired by the singer. Laura Watson reviews.

Nothing Compares to You promises ‘an intimate, evocative celebration of the life and legacy of musician and political icon, Sinéad O’Connor.’ In this collection of twenty-five essays, ‘a renowned and multi-generational group of women and nonbinary authors come together to pay tribute to Sinéad’s impact on their own lives as humans and artists and on our world at large.’ Editors Sonya Huber and Martha Bayne are US-based writers and journalists, as are most of the contributors. Sinéad Gleeson is the only author from Ireland. Just a few of the authors have worked in the music industry, as producers, performers, and journalists. The profile of these essayists – generally, women writers in the US, many of whom lived their formative years in parallel to O’Connor’s ascent to global fame from 1987 to 1992 – seems to signal that the artist predominantly ‘belonged’ or spoke and sang to Gen X women who internalised liberal Western values. This framing is provocative: does it represent O’Connor’s main audience? If so, what does that say about her artistic impact and wider cultural imprint?

Given the quantity of essays in the Huber and Bayne volume, I can only discuss a few in detail. To start, an overview may be useful for prospective readers. Each piece is titled after an O’Connor song, the order mostly mirroring the chronology of the artist’s discography. Her duet with U2’s Edge on ‘Heroine’ (1986) lends its title to the opening piece; the final one pays tribute to ‘Horse on the Highway’, a 2020 demo for an album yet to be released. Most essays in between lean heavily on the musician’s earlier rock and pop-oriented output. Five invoke songs from her debut album The Lion and the Cobra (1987); eight are named after tracks from I Do Not Want What I Haven’t Got (1990); one centres on ‘My Special Child’ (a single from 1990); one draws from Am I Not Your Girl? (1992); and one cites her rendition of Bob Marley’s ‘War’ (on SNL in 1992). That SNL performance ended with O’Connor altering the closing lyrics of ‘War’ to condemn child abuse and ripping up a picture of the pope. It also saw her exiled from the mainstream music industry. Still, she released seven more studio albums from 1994 to 2014, producing an eclectic body of work which departed considerably from her earlier sound. While three songs from Universal Mother (1994) are discussed, comparatively little space is given to her later, twenty-first-century output. It would be unfair to criticise the book unduly for this, as that imbalance is a function of the music history and media narratives which until very recently reduced O’Connor to a female rock rebel who lost her way in 1992.

Touchstones of her life story

Most essays comprise deeply personal stories, yet there are recurrent themes such as surviving abuse, what it means to mother, grief, feminist resistance, and the role of religion and faith in women’s lives. Anyone who has followed O’Connor’s career will know that those themes are also touchstones of her life story and lyrics. They reverberate here as the authors tend to identify with the singer or feel a sense of shared history with her. Returning to the question of how that framing represents the artist’s audience, on the one hand it succeeds at showing how O’Connor was a beacon for people, especially women, who felt marginalised and struggled to find their place in the world. On the other hand, that focus means the project risks losing readers who are primarily music fans and want to think more about its subject: although each piece is ostensibly themed around a song, some have little to say about the track in question and O’Connor herself recedes out of view.

Other essays centre the musician while still finding space for the author’s story. Allyson McCabe sheds light on O’Connor’s last creative phase by discussing her little-known 2020 demo ‘Horse on the Highway’, hearing in it the ‘unguardedness’ of an ‘anguished voice… resolving in her music what could not be resolved in life.’ That vulnerability, McCabe explains, inspired her to ‘honour Sinéad’s bravery’ by revealing painful truths about her own life in her writing. As a journalist who interviewed O’Connor in 2021, she brings further authentic insights to this piece.

An artist still evolving

Sinéad Gleeson’s essay is similarly informed by encounters with the singer in later life, at and behind the scenes of the last concert she played in Dublin, in 2019. Recalling her performance of ‘Milestones’, another new song also only available as a demo, and the singer backstage ‘wearing a hijab…smiling, happy, holding tight to [her daughter’s] arm’, the author gives readers a glimpse of O’Connor as a creative and contented middle-aged woman, who had recently converted to Islam. That version of Sinéad O’Connor – a woman who had found some peace in her fifties, a mother of adult children and a grandmother, an artist who was still evolving – is rarely acknowledged in the public discourse. Most of the obituaries in 2023 fixated on her youthful achievements and beauty. For that reason, essays such as those by Gleeson and McCabe matter.

Most essays comprise deeply personal stories, yet there are recurrent themes such as surviving abuse, what it means to mother, grief, feminist resistance, and the role of religion and faith in women’s lives.

Sharbari Zohra Ahmed is also attentive to the older O’Connor – or Shuhada’ Sadaqat as she renamed herself when she became a Muslim in 2018. Ahmed, describing her own struggles with what it means to be a Muslim woman, credits O’Connor/Sadaqat with teaching her to see Islam in a new light: ‘she viewed it as expansive; it made sense to her and was now making sense to me.’ This, the opening essay in the book, challenges the orthodoxy that centres Catholic Ireland in O’Connor’s life. Even if one is not wholly convinced by the interpretation of ‘how Islamic’ the song ‘Heroine’ is – she wrote and recorded it in 1986, decades before converting – Ahmed’s perspective is important because it positions the artist as a figure relevant to the Muslim world, with a reach beyond the Western audiences with whom she is normally associated. Porochista Khakpour, in an epistolatory piece that recalls O’Connor’s open letters to various celebrities and politicians, also cites Islam as a point of connection between the artist and herself.

There is still plenty of reference to repressive Catholic Ireland and O’Connor’s defiance of its values, but much of it hinges on her SNL protest. With several authors noting this incident, it becomes something of a trope, reinforcing the existing (and US-centric) narrative about the musician. Viewing her through a US lens, as many contributors do, perhaps explains a few inaccuracies about Ireland, such as the claims that the young Sinéad was sent to a ‘Waterford Laundry’ (it was An Grianán reformatory school in Dublin) and that her parents divorced in the 1970s (when it was prohibited). Another way in which O’Connor took a stance against repressive Ireland, especially its systemic misogyny, was by creating work about women’s bodies and reproductive lives. As stated in her memoir Rememberings, she wrote ‘Three Babies’ (1990) about three miscarriages she suffered. Another song, ‘My Special Child’ (1991), refers to an abortion she had and the circumstances that prompted this decision. Two essays engage with these songs: Brooke Champagne takes ‘Three Babies’ as a departure point for reflecting on her own complicated pregnancy history, while Jill Christman responds to ‘My Special Child’ with a personal piece about how circumstances shape the choices women make about motherhood.

Vulnerability

A few contributors are perceptive about how O’Connor projected vulnerability in her art. Christman hears the strange absence of a chorus and the interjection of a spoken address in ‘My Special Child’ as means of ‘processing trauma through music.’ Stacey Lynn Brown’s meditation on ‘I Do Not Want What I Haven’t Got’ sits with the a cappella nature of the recording and the almost uncomfortable intimacy the exposed voice creates with the listener. ‘Sinéad’s breath is audible, the gasping, deep inhalations’ demand ‘the listener’s willingness to follow breath wherever it may lead’, Brown writes. Another performance produced to focus on the voice, albeit with a minimalist droning accompaniment, is ‘Molly Malone’ on Sean-Nós Nua (2002). Nalini Jones observes that ‘O’Connor slowed the tempo to the halting progress of a barrow over cobblestones’, thereby giving insights into how the singer’s interpretation of the material rejects clichéd ‘singsong arrangements’ for tourists and returns to its roots as a lament. Weaving in her own history as a producer in the folk scene, Jones argues that O’Connor belongs to the folk tradition of voices ‘that speak truth to power’ and ‘aren’t seeking to make people comfortable.’

To conclude, let’s return to questions raised earlier – what does this book as a whole suggest to us about this artist’s reach and legacy? Arguably its main achievement is highlighting her broad social and cultural impact: she was an icon of a liberalised Ireland, an internationally recognised radical figure, and an empowering, empathetic voice for women coping with a range of circumstances, from the patriarchal dictates of religions to private grief about pregnancy loss. O’Connor’s musical output is discussed to some extent too, but coverage of her career trajectory is uneven, with much variability in how her work is analysed. For readers who are fans of the musician, there is much to explore here. Those of a more critical or musicological persuasion should also find several essays informative and thought-provoking. But the patchy consideration of O’Connor’s place in music history, understandable though it may be in a collection of personal pieces, seems to slightly undermine the book’s aim of celebrating its subject. There is still much to be said in the posthumous appraisal of O’Connor as an artist.

Nothing Compares to You: What Sinéad O’Connor Means to Us, edited by Sonya Huber and Martha Bayne, is published by Atria/One Signal, imprints of Simon & Schuster. Read more from The Journal Of Music here