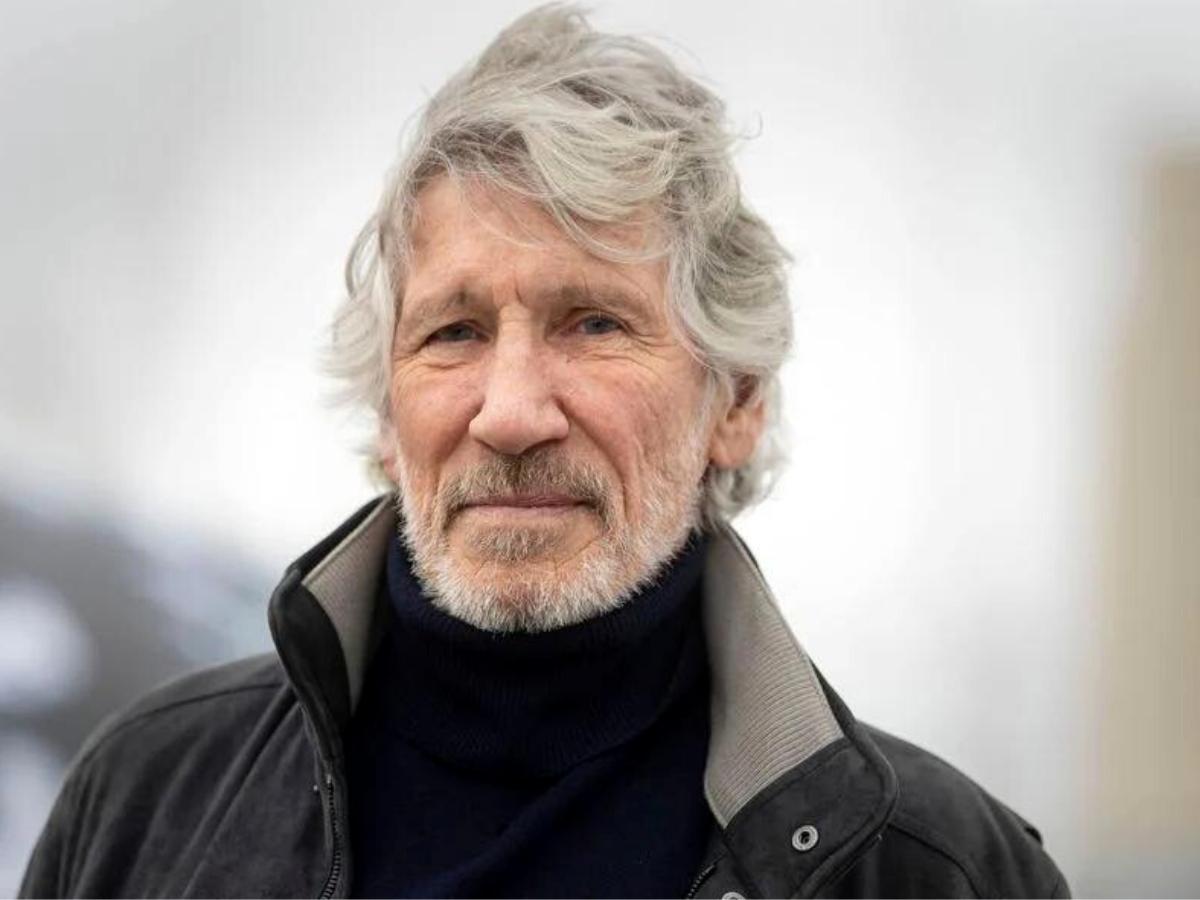

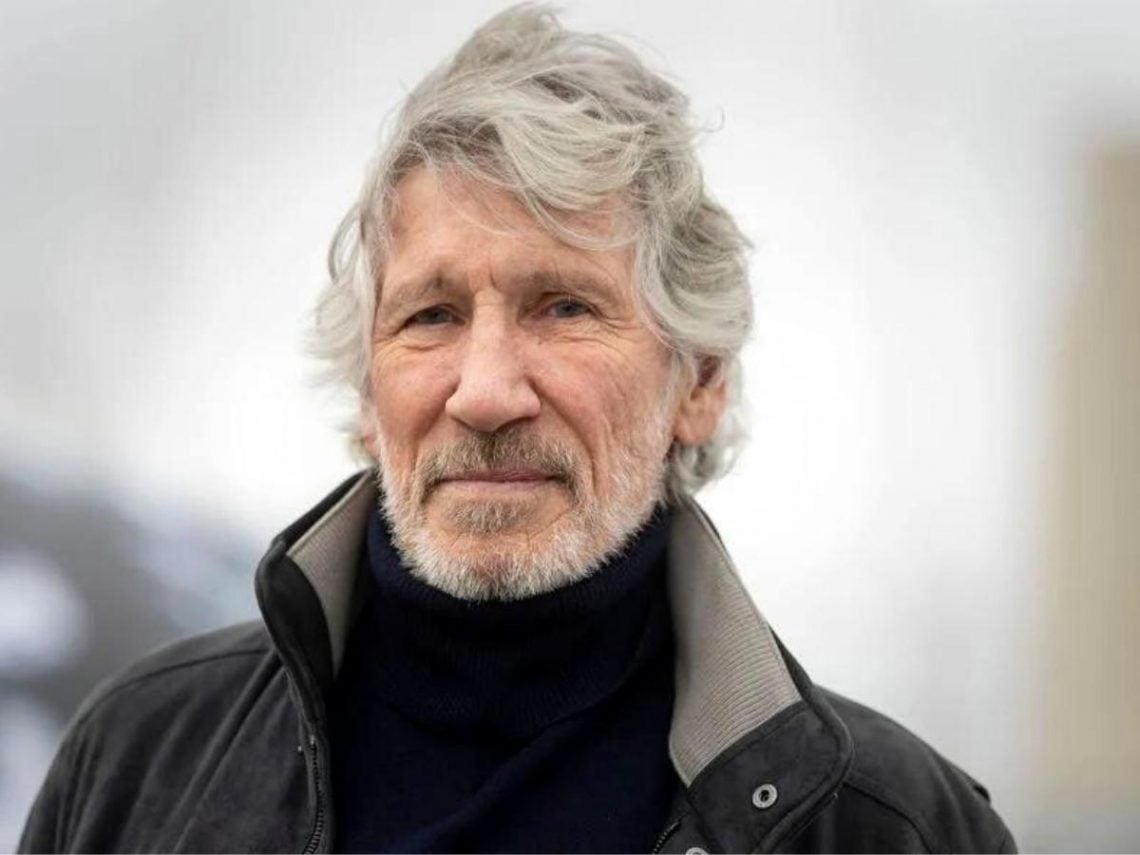

(Credit: Alamy)

Mon 15 September 2025 18:00, UK

If there’s one thing that anchors Roger Waters’ artistry, be it Pink Floyd or his solo work, it’s a restless pursuit of new creative terrain.

As the 1970s rolled along, Waters’ emerging principal songwriting and conceptual steer across Pink Floyd’s golden album run would end the decade on a completely different plane of visionary inspiration than how they started it, shuffling around in aimless circles on 1970’s Atom Heart Mother, to weaving gripping rock operas on 1979’s The Wall.

Greater success and album high marks came with deeper fractures. With cracks forming in Pink Floyd’s foundations as early as the mammoth-selling The Dark Side of the Moon, relationships between Waters and the rest of the band hit a breaking point after The Wall Tour, limping on for 1983’s The Final Cut—minus keyboardist Richard Wright—before Waters officially disbanding two years later. Respective guitarist and drummer David Gilmour and Nick Mason, with Wright back in the fold, ploughed on under the Pink Floyd name from then on.

Yet, it was Waters’ work that possessed the frissons of vitality that used to spark Pink Floyd’s classic material. While Pink Floyd under Gilmour’s captaincy would drop the soggy A Momentary Lapse of Reason and the marginally better The Division Bell, Waters would dream up innovative multi-media projects such as 1987’s Radio KAOS, conjuring a captivating critique of nuclear threat set to a rock narrative as cohesively realised as The Wall, matched with a live extravaganza that beat U2 to the media overload arena spectacle they’d unleash on their Zoo TV Tour by five years.

Waters would resurrect the Pink Floyd canon, dusting off The Wall for frequent live shows and even revisiting The Dark Side of the Moon for his own ‘redux’ release, but a bolder intuition for new projects guided Waters to a degree that seemed to elude the remaining Pink Floyd members. Such a strident step into the unknown was evident in Waters’ embrace of opera.

First completed and recorded in 1988, with an official CD release arriving in 2005, Ça Ira saw Waters compose an 82-piece orchestra work on the French Revolution, based on the libretto by chanson writers Étienne and Nadine Roda-Gil. Despite garnering some high-profile fans, the then-president, François Mitterrand, pushing the Paris Opera to stage the show for its bicentennial celebrations of the revolution, critical reception was mixed, Ça Ira facing criticisms of its narrative flow and conservative score. Waters was prepared for the shade thrown by classical connoisseurs, however.

“I understand the knives will come out—that’s inevitable,” Waters confessed to CDNow in 1999. “But one of the problems that people in the classical world have is how many recordings of Mahler or Beethoven symphonies can you make? They’re always looking for new music, but many of the new serious composers are into academic forms, which strike some people as sterile and cold.”

He added, “I think I’ve made a work that is melodic and emotional; I think I’ve done something that can move people. The libretto is very much relatable to my earlier work because it has that humane element.”

Grand narratives and compositional scope were nothing new to Waters. Honing keen conceptual arcs to Pink Floyd’s defining albums, the leap into the world of classical opera is a more obvious project for an artist of the progressive world than Paul McCartney or Billy Joel’s forays into respective symphony or concerto works.

Yet, unconcerned with chasing the plaudits of classical elite gatekeepers, Waters’ drawing of the French Revolution’s liberatory themes in such a heartfelt way stands Ça Ira as one of the former Pink Floyd bassist’s most hopeful creations of his career.

Related Topics