Credit: Sinhyu / iStock / Getty Images Plus

Credit: Sinhyu / iStock / Getty Images Plus

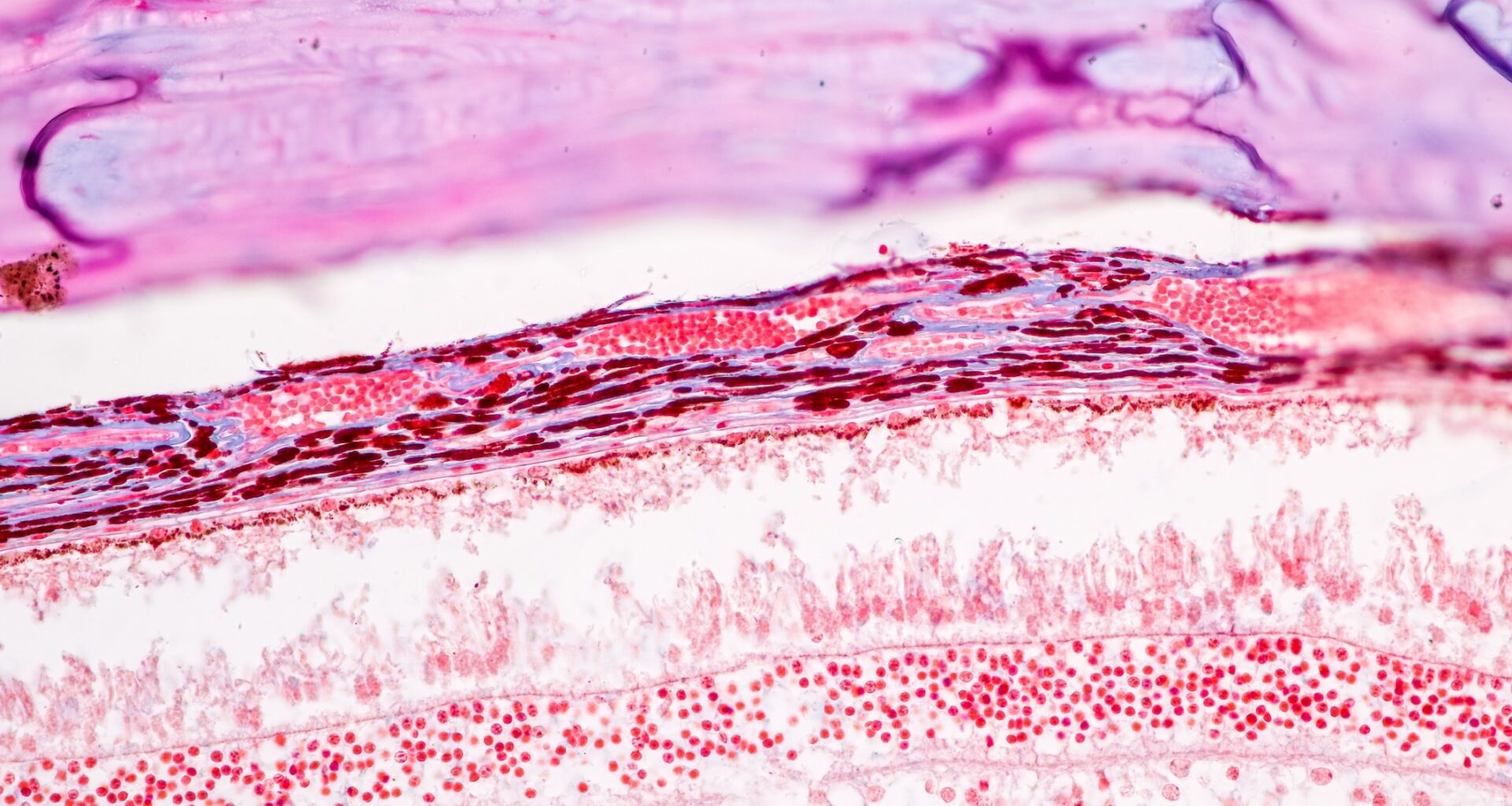

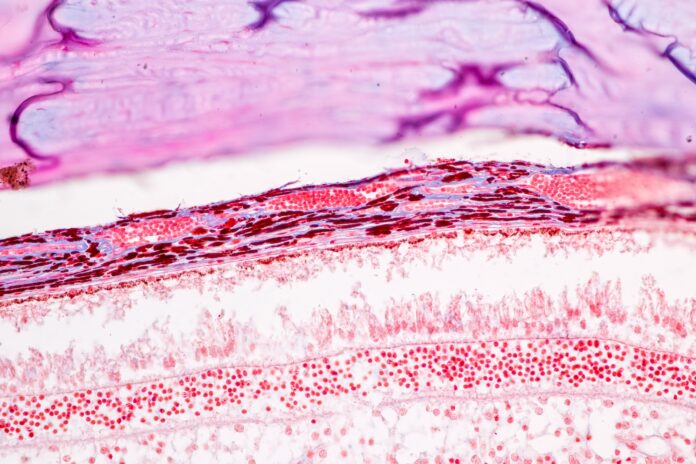

A new study has identified a link between genetic risk factors for schizophrenia and subtle thinning in specific retinal layers, offering a potential noninvasive biomarker for early indications of the complex mental disorder. While retinal thinning has previously been documented in individuals diagnosed with schizophrenia, this study breaks new ground by linking these changes to genetic risk in otherwise healthy individuals, strengthening the evidence that the changes in the retina might be due to preexisting genetic predispositions rather than the disorder itself.

A genetic connection to retinal thinning

The Nature Mental Health study, involving nearly 35,000 participants from the UK Biobank, explored the relationship between polygenic risk scores (PRS) for schizophrenia and retinal morphology in individuals without a schizophrenia diagnosis. Focusing on individuals without a diagnosis allowed the researchers, who were mainly from the University of Zurich and ETH Zurich, to avoid potential confounders like smoking, antipsychotic medication, or lifestyle factors that are commonly found in patients with diagnoses.

Researchers found that higher schizophrenia PRS was associated with a reduction in the overall thickness of the macula, located at the center of the retina and rich in neurons, which is crucial for detailed vision. This change reflects a potentially significant neurodegenerative process linked to genetic susceptibility. In addition to overall macular thinning, the study uncovered a specific connection between neuroinflammation-related genetic pathways and the ganglion cell-inner plexiform layer (GCIPL) of the retina. Participants with higher PRS tied to neuroinflammation genes exhibited significant thinning in this layer, suggesting a role for inflammatory processes in the development of retinal changes.

The researchers explored potential mechanisms linking genetic risk to retinal changes. One possibility lies in neuroinflammatory processes. Elevated PRS for schizophrenia were correlated with higher levels of C-reactive protein (CRP), a marker of systemic inflammation. CRP levels partially mediated the relationship between genetic risk and GCIPL thinning, suggesting that inflammation is a contributing factor. “Neuroinflammatory cascades may disrupt the integrity of retinal structures and contribute to the thinning we observed,” the study’s authors noted. “This aligns with broader theories about inflammation’s role in schizophrenia and neurodegeneration.”

Implications for early detection and research

The study’s findings open new avenues for understanding schizophrenia and developing early detection tools. Retinal imaging, a noninvasive and widely available technique, could serve as a window into the brain, offering clues about genetic and neuroinflammatory pathways linked to the disorder.

However, the researchers caution against overinterpreting their results. “Retinal thinning is unlikely to be a definitive diagnostic tool on its own,” they said. “Instead, it may provide valuable context when combined with other risk factors and biomarkers.”

Limitations of the study include its focus on individuals of British and Irish descent, which may restrict the generalizability of the findings. Additionally, while robust statistical methods were used, the explanatory power of PRS remains modest. The researchers emphasize the need for further studies to disentangle the complex interactions between genetic risk, environmental factors, and comorbid conditions that may influence retinal health.

The path ahead

Future research should aim to explore gene-environment interactions that could amplify genetic risks, such as smoking or metabolic dysfunction. Understanding these dynamics may provide a clearer picture of how lifestyle factors influence retinal and neurodegenerative changes in genetically predisposed individuals.

Despite these challenges, the study represents a significant step forward in linking genetic risk factors for schizophrenia to structural changes beyond the brain. “The retina may not just reflect the brain’s health but also mirror the genetic complexities of schizophrenia,” the authors concluded. By illuminating these early changes, the research offers hope for advancing our understanding of this enigmatic disorder and paving the way for innovative approaches to prevention and treatment.