Facebook

Twitter

Reddit

WhatsApp

Messenger

Email

Print

Amidst everything on the news last week, from revolutionary events in Indonesia and Nepal, to the shooting of Charlie Kirk, a major political crisis is unravelling in France which has given birth to the Bloquons tout (Block Everything) movement.

Whilst this might not seem as dramatic as the events in Indonesia and Nepal, the very same contradictions that led to those events are coming to the surface in France. Sooner or later they will express themselves with greater force, bringing into question capitalist rule itself, which has big implications that go far beyond France.

The following article draws together many of the threads of our analysis of the burgeoning crisis in France that we have carried here on marxist.com over the past few months and points to where events are heading. We recommend our comrades check them out, including the editorials of the French section of the RCI, the Parti Communiste Révolutionnaire, many of which have been translated into English and can be found here, and all of which can be found in French here.

We also recommend the last episode of Against the Stream.

Public debt balloons

French capitalism is facing an avalanche of debt. The state owes €3.5 trillion, 113 percent of French GDP. Its budget deficit is almost twice the 3 percent limit formally set by the EU. This year alone it is estimated to spend around €66 billion just to pay the interest on this debt. To put this into perspective, the national education budget last year was €65 billion!

In fact, the cost of borrowing that the French government has to pay on its loans now exceeds that of Greece – the previous ‘sick man’ of Europe. The payment of interest is expected to reach nearly €100 billion by 2028 in the ‘best’ case scenario.

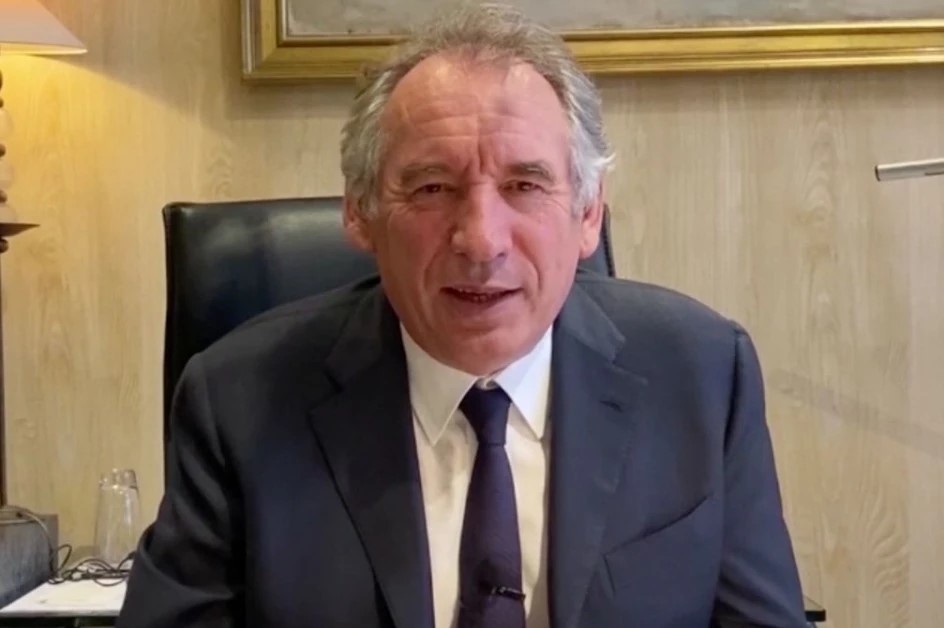

It is in this context that, back in July, the outgoing Prime Minister, François Bayrou, warned that if the budget deficit was not cut, France would face a debt crisis along the lines of Greece in 2010, claiming “we have become addicted to public spending”.

Bayrou’s proposed solution was to massively cut public spending and to increase taxation on the working class and small businesse / Image: fair use

Bayrou’s proposed solution was to massively cut public spending and to increase taxation on the working class and small businesse / Image: fair use

He laid out a plan for €44 billion in ‘savings’, made up of tax rises, spending cuts on healthcare, subsidies on certain medicines for the sick, curbs to pensions and social welfare benefits, such as unemployment benefits and long-term sick leave. He even proposed scrapping two public holidays (Easter Monday and ‘Victory Day’).

At the same time, military spending was spared from the proposal, being generously allocated €6.5 billion over the next two years, to be financed through the proposed cuts to other areas, rather than taking on new debt.

The president of the government’s ‘Council of Economic Analysis’ said: “There are not one or two measures that can bring us to reduce the deficit enough. We need an array of measures.”

And so, naturally, Bayrou’s proposed solution was to massively cut public spending and to increase taxation on the working class and small businesses, in order to try to pay back this debt. This programme perfectly reflected the interests of the French ruling class.

There is a cruel logic to these cuts targeting the masses. Any attempts to tax big business or the wealth of the rich to plug the gap would only further undermine the stability and competitiveness of French capitalism, as investors take their money elsewhere.

The reality is that capitalism in France has been in decline for several decades, and is less and less able to compete on the European and the global market – particularly against German and Chinese capitalism.

This crisis has also been intensified by the decline of French imperialism, particularly in West and Central Africa. This has threatened French capitalism’s access to cheap resources and captive markets, at a time when French industry is already falling behind its rivals.

The 2008 crisis was a major blow to the French economy. The state spent around €360 billion of public money to save the banks and large French companies, pushing public debt up. Rounds of austerity followed. The ‘yellow vests’ (gilets jaunes) movement that erupted in 2018 was in no small part a response to this.

Huge amounts of borrowed money have subsequently been pumped into the system in the course of the COVID-19 pandemic – around €424 billion – in order to avoid economic collapse, and with it the threat of revolution. However, this led to a surge in inflation, which was further compounded by the impact of the Ukraine war and the consequent energy crisis in Europe, with huge amounts again spent on subsidising energy costs.

It should also be said that much of the money, which the government has borrowed to fund tax exemptions and subsidies for the large companies, has simply ended up in the bank accounts of shareholders.

The government’s huge budget deficit and unsustainable debt therefore has nothing to do with an ‘addiction to public spending on the part of workers’; it is the product of the irreversible decline of French capitalism, and the degenerate, parasitic character of the French capitalist class. Unable to develop production in any meaningful way, all the French capitalists can do is maintain their profits at the expense of the state, which has taken on more and more debt in order to keep itself afloat, with very little to show for it.

Today, France is trapped in a spiral of debt, with borrowing costs rising as investors fret that it won’t be able to pay back all its debts, thus pushing debt up further. Just before the weekend, France’s credit rating was downgraded to its lowest level on record. Political crises and the high turnover of governments only serve to further rattle the confidence of lenders, thus pushing up borrowing costs ever higher as time goes on.

The bourgeois press sometimes suggests that the debt crisis isn’t that big of a deal. Every country has debt, the system can cope with it, and so on. But this is completely false, and France is a case in point.

House of cards

The historic scale of the cuts planned in Bayrou’s proposed budget were deemed virtually impossible, politically speaking, to pass through the National Assembly.

Every attempt to stabilise the economic equilibrium is having the effect of disrupting the social and political equilibrium.

On the one hand, the economic crisis has triggered a major political crisis in the government, which does not have a majority in the National Assembly. With at best only 215 seats out of 577, Macron’s socle commun (‘common base’) needs the support of one or more of the opposition parties.

But in this completely fractured parliament, everyone is desperate not to commit political suicide before the next election. Marine Le Pen’s Rassemblement National (RN), which is the biggest single party in the Assembly with 123 seats, and the so-called ‘centre-left’ Socialist Party had saved the government earlier this year, when they abstained on the motion of no confidence brought against Bayrou. But now they have no desire to take the blame for his brutal austerity programme.

Jean-Luc Mélenchon’s left-wing party, La France Insoumise, has correctly rejected any deal with the government, and has called on Macron to resign from the presidency / Image: MathieuMD, Wikimedia Commons

Jean-Luc Mélenchon’s left-wing party, La France Insoumise, has correctly rejected any deal with the government, and has called on Macron to resign from the presidency / Image: MathieuMD, Wikimedia Commons

Likewise, Jean-Luc Mélenchon’s left-wing party, La France Insoumise (LFI), with its 72 seats, has correctly rejected any deal with the government, and has called on Macron to resign from the presidency.

This is where the vote of confidence that Bayrou moved on himself came in on 8 September, which unsurprisingly led to his downfall. Knowing that he could not pass his proposed cuts, Bayrou chose instead to go down in a blaze of glory (in his own eyes at least). Before being kicked out of office by the assembly, he lectured the deputies: “You may have the power to bring down the government, but you cannot efface reality,” presumably hoping to one day return to prominence on the slogan, “I told you so!”

Now Bayrou has been replaced by Sébastien Lecornu – the previous defence minister and close Macron ally – who becomes the third Prime Minister of France in 12 months!

The problem for the ruling class, however, is not just political fragmentation. This is the symptom of something much more profound: the volcano they are sitting on, which makes it impossible to push through cuts on the scale that they need. The result is a weak and permanently paralysed parliament.

The entire regime is detested by most. Macron’s popularity is at a record low since coming into power in 2017, lower even than at the time of the Yellow Vests movement in 2018. A chasm has palpably opened up between the politicians, the government and the needs of ordinary people.

Each time Macron has brought forward a new prime minister, far from bringing him stability, it has only further undermined both his credibility and that of the whole establishment. People are forced to conclude that it doesn’t matter if you change one or two positions at the top, the whole thing has to go. This sentiment has developed on a much bigger scale than at any other point in the past.

Bloquons tout

While the politicians have scrambled to save their careers, and will once again take part in a game of musical chairs and further ructions, the anger and hatred of the masses has been brewing. This is the context in which the Bloquons tout movement has erupted.

Calls were put out on social media as early as July to bring the country to a halt on 10 September. What is striking is this call out emerged spontaneously – it did not come from any traditional parties or unions. It spread on TikTok, Telegram, Instagram, and so on.

The crowd at Chatelet, Paris, for the #BloquonsTout protest against austerity and the Macron regime. Video @LucAuffret pic.twitter.com/1nwbHOngIc

— Jorge Martin ☭ (@marxistJorge) September 10, 2025

Following this, Bayrou announced the confidence vote in himself. Part of his calculation was to use this as an attempt to diffuse the movement before it even took off. But, if anything, Bayrou’s downfall has spurred things on further. The call of the movement became, “Bayrou out on the 8th, Macron to resign on the 10th”.

On 10 September, France saw a big mobilisation. Several hundred thousand people took part across France.

700 workplace unions had put in calls for strikes; among them teachers, civil servants, transport workers, energy workers, as well as other sectors. School students and university students were out on the streets, with many reports highlighting the large presence of the youth. Road blockades, demonstrations, pickets and general assemblies were held.

Both big and small cities saw mobilisations, such as Nantes, Montpellier, Lyon, Paris, Marseille, Rennes. Rennes is a city with only around 220,000 residents, but about 15,000 took part in the mobilisation there.

Riot police brutally attacked people for taking part, with videos emerging on social media of protestors being beaten, dragged away and arrested, and teargas being used to try to disperse protesters.

Some photos show young people holding signs saying ‘Macron: it’s your turn’; graffiti was written on a lion statue: ‘The Lion: eater of Macron’; a mock funeral was held for capitalism by some workers on strike, with “capitalism, dead in 2025” written on one end and the French stock exchange on the other with the same end date.

Lion mangeur de macron pic.twitter.com/CN0gUNuSI5

— Mobu 🌸 (@ShadicPotato) September 10, 2025

Another sign, held by members of a family who came out on strike altogether, had a very interesting message: “We are neither right nor left, we are from the bottom, and we’re coming for those at the top”.

These are very profound signals that workers and young people will not tolerate the status quo for much longer. And they are also important signs that 10 September was not just about celebrating Bayrou’s departure, it was not just about the desire to bring down Macron – although that is a very important part of it.

Bloquons touts – “Block Everything” is what France is shouting on the streets. Yesterday it was Nepal, today it’s France. The world is slowly rising against injustice and failed leadership. pic.twitter.com/V480NiXTUc

— sangwan (@SangwanHQ) September 10, 2025

It’s about everything they represent. There are huge reserves of anger looking for a direction of release, against austerity, destruction of public services, against the sham of bourgeois democracy, corruption, the complicity of the government in genocide in Palestine, the system which works for the rich and creates misery for everyone else.

There is a deep and widespread desire for a complete change.

Role of the trade union leaderships

The trade union leaders have called for a day of action on 18 September – eight days after the first mobilisation. This is already more than they would like – they didn’t call the movement of 10 September, and now they have been forced to call for more action.

No one has forgotten their usual tactics, applied over years: attempt to divert the potential of mass movements into isolated days of action. Against the pension counter-reforms, they organised 14 days of action spread over six months.

Some of those protests nonetheless galvanised millions of people out on the streets. But they failed to escalate the struggle against Macron. This is what the trade union leaders wanted: for the movement to run out of steam, exhausted, and for people to return home to what they see as ‘normal’, to let the union leaderships take back ‘control’ of the situation.

In the end, the pension counter-reform was scandalously pushed through by Macron using the notorious Article 49.3 of the Constitution, without a parliamentary vote

It is no coincidence that on 10 September, rather than leave it up to the official ‘leaders’, you had assemblies of, in some cases, thousands of people, discussing the question, ‘what next?’ Quite simply, many have concluded that isolated days of action do not work.

In an interview, an actor on strike said, “Unions and parties don’t do what’s needed. Those in power couldn’t care less about our protests. Demonstrations aren’t enough anymore. We need to go further… The important thing is to make ourselves heard and get rid of Macron!”

While there is wariness on the part of the masses towards what many see as pointless ‘days of action’, the question remains to be answered then: which way forward?

A lead could be given by Mélenchon and LFI, who have called for an open-ended general strike. Unité CGT, the magazine of the left wing of the Confédération Générale du Travail (the biggest union in France), has also put forward a militant programme of class struggle. They have called for a general strike, the occupation of workplaces, and a return to the traditions of June 1936 and May 1968, which are historic events in the class struggle in France.

This is significant. France has rich revolutionary traditions, which have imprinted themselves on people’s consciousness and have been passed down through generations. Given the immense pressure that the masses are under, we may well see a major escalation on 18 September.

This would be a test for La France Insoumise and the left wing of the CGT. Nothing would stop them from convening mass assemblies to organise the movement around a radical programme if they chose to do so.

These assemblies should be called, so that they might become a launch pad for an escalation of the movement, not in the form of a series of one-day ‘general strikes’ imposed from above, but a programme of renewable strikes, in which the workers regularly vote on whether to keep the strike going, rather than returning to work at a predetermined point. The expansion of this movement of renewable strikes throughout the economy would be by far the most powerful weapon with which to bring down Macron, Lecornu and the entire regime.

If Mélenchon were to refuse to carry out the austerity demanded by the ruling class, then this would be supported by the entire working class / Image: Pierre Selim, Wikimedia Commons

If Mélenchon were to refuse to carry out the austerity demanded by the ruling class, then this would be supported by the entire working class / Image: Pierre Selim, Wikimedia Commons

The role of the working class in the Bloquons tout movement already poses the question of who should really run society. It has the potential to demonstrate the power the working class holds if it develops further.

For instance, if 18 September is a success, with assemblies staying in place to decide on the next steps, this could galvanise the support of broader layers of the working class who were previously hesitant to get involved (precisely because they concluded that isolated days of action led nowhere). It could give the workers a renewed confidence in their power as a class and push the movement further on the basis of class struggle methods. Given the mood on the ground this isn’t out of the question.

However, it must be explained from the outset that it will not be enough to bring down Macron if the system he represents remains intact. The programme of LFI contains a number of progressive demands for nationalisations, lowering the retirement age, funding public services, raising the minimum wage, and so on. But if it should come to power, it will be confronted with the same question as any government: what to do about the debt?

If Mélenchon were to refuse to carry out the austerity demanded by the ruling class, then this would be supported by the entire working class. This would not prevent finance capital from exerting unbearable pressure to bring him into line. Bayrou has already warned that France might have to seek assistance from the IMF. In such a scenario, Mélenchon would be faced with the same choice as Alexis Tsipras in Greece ten years ago: either capitulate and betray the working class, or break with capitalism.

The only way out of the debt crisis is for a workers’ government to repudiate the debt, nationalise the banks and monopolies that have dragged France into this crisis, and begin to plan the economy democratically in order to provide for the needs of all.

However the movement develops, we can be sure of one thing. The crisis of capitalism in France and the scale of attacks the ruling class will unleash on the working class, will force the class struggle to go beyond the control of the trade union leaderships at a certain point. What is required is a leadership capable of organising this movement, galvanising it with a bold socialist programme and leading it to victory.

Whilst France is at the forefront of the crisis in Europe, similar situations are being prepared everywhere. In Europe, Britain is facing its own debt crisis, no less serious than that of France. Meanwhile, Germany, the most powerful economy in Europe, is facing a severe economic crisis, having entered a third consecutive year of recession.

The ruling class are unable any longer to allow for the standard of living that the working class attained in the postwar period. They require decades of austerity. As German Chancellor Merz put it, “the welfare state as we have it today can no longer be financed by what we produce in our economy – we cannot maintain the level of living standards of the past”. On the basis of capitalism, he is absolutely right.

The political implications of the crisis are enormous, and as France shows, the basis has been laid for a major intensification of class struggle across the board.

Facebook

Twitter

Reddit

WhatsApp

Messenger

Email

Print