Pupils in Wales leave school knowing more about Nazi Germany than the “profound impact” of local Welsh history, an education lecturer has said.

It is 60 years since a Welsh-speaking village was flooded to supply Liverpool with drinking water, and Dr Huw Griffiths, senior lecturer at the University of Wales Trinity Saint David, believes there is a “lack of focus on local history” such as this within Wales’ curriculum.

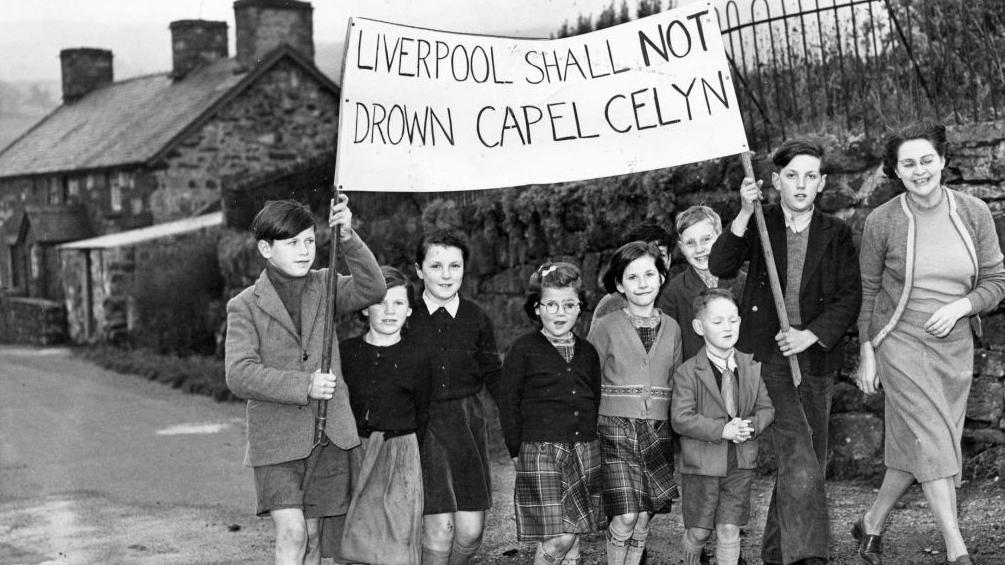

Despite overwhelming opposition from Welsh MPs, mass protests, and an attempt to bomb the site of the proposed dam, more than 70 people were forced out of their homes in Capel Celyn, Gwynedd, and rehomed against their will.

Its 12 farms, school, chapel and post office, all disappeared under water to make way for the new Tryweryn reservoir.

The Welsh government said Welsh history had been “mandatory as part of the Curriculum for Wales since 2022”, including learning about children’s own locality.

A statement said the independent regulator, Qualifications Wales, had engaged “extensively” with teachers, universities and colleges.

“Learners are taught how history, language, diversity and culture have shaped Wales to become the proud and unique nation it is today,” it added.

But Mr Griffiths argued that secondary education in Wales was often guided by GCSEs and A-Levels, which he said meant the tales of “who we are as people get lost”.

“It’s about a deeper understanding of who we are, developing an idea of belonging and who we are as people,” Dr Griffiths added.

“Tryweryn was a remarkable period in history, which had a profound impact on us,” said Dr Griffiths, describing it as “just one story” of Welsh heritage.

Some historians say the flooding, despite overwhelming opposition, highlighted Wales’ “powerlessness” [National Library of Wales]

As the chairman of the Welsh Heritage Schools Initiative, which encourages schools to teach Welsh history, Dr Griffiths also said the new GCSE was a “missed opportunity”, as there is a lack of focus on Welsh history.

He said the vast majority of teaching around Tryweryn was taught by Welsh language departments in secondary schools, and there needs to be a refocus on local Welsh history in schools.

“Our children still leave school knowing more about Nazi Germany than Welsh history,” he added.

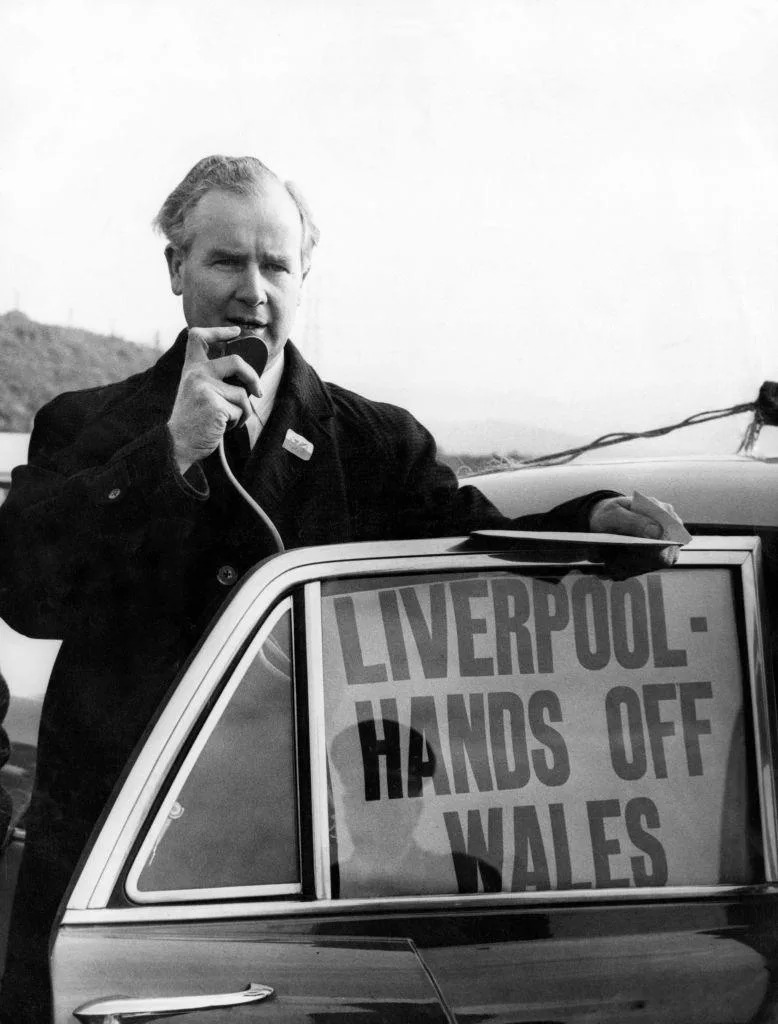

Gwynfor Evans was elected as Plaid Cymru’s first MP one year after the official opening of the dam [Getty Images]

In the summer of 1955, residents of Capel Celyn learnt their village had been earmarked as the site for a new reservoir to provide drinking water for Liverpool.

In a fight to try and save their homes, nearly a decade of protests and marches through the streets of Liverpool ensued, but the plans of the Liverpool Corporation moved forward relentlessly.

Prior to Tryweryn, Liverpool was already getting its water from Wales – but the city’s council argued there wasn’t enough of it.

As demand for water in Liverpool grew, politicians saw a need for a bigger, better water supply, so building the reservoir by drowning Capel Celyn was seen as serving a vital and greater good.

People began moving out of their homes in 1963 and the dam officially opened on 21 October 1965.

The decision is regarded as a key point in shaping Wales’ political and cultural landscape, as the unheard voices of the drowned village “crystallised Wales’ powerlessness“, according to campaigners.

An unofficial memorial is near Llanrhystud, Ceredigion, where “Cofiwch Dryweryn”, or “Remember Tryweryn”, was painted on a stone wall by political activist and author, Meic Stephens.

Initially seen as graffiti, it has become a slogan for Welsh nationalist groups.

The slogan was painted on a jetty in solidarity in Milford Haven, Pembrokeshire, in 2021 [Getty Images]

About five years ago, vandals blighted the sign with graffiti, in what was regarded as a “hate crime”.

Many volunteers rallied together to return the sign to its former glory and it raised awareness of the town’s history, with the slogan being spotted among other parts of Wales in a show of solidarity.

Evan Powell, from Yes Cymru, said the role of the murals and the backlash of the damage played a huge part in the “stratospheric rise of support for Welsh independence” as well as growing the membership of Yes Cymru.

“What happened at Tryweryn is no longer just a story from 60 years ago – it is still deeply relevant today and resonates with people when they learn about it, or with those already familiar,” he said.

“It stands as a stark example of the democratic deficit Wales faces, highlighting that Wales lacked true agency then and continues to lack it now.”

The village primary school closed its doors in July of 1963 [National Library of Wales]

For those who lived it, the drowning of Capel Celyn sat heavy on their shoulders.

The youngest protester on Liverpool Town Hall was Eurgain Prysor Jones, who was just three years old in 1956.

Speaking on the 50th anniversary, Eurgain recalled carrying a “massive poster” which was bigger than her, and described being met by an “awful” reception in Liverpool.

“People were spitting at us and throwing rotten tomatoes at us. It was an awful disappointment,” she said.

Forty years after the opening of the reservoir, Liverpool City Council issued an apology over Tryweryn for “any insensitivity shown” by the previous council’s endorsement of the proposal to flood the valley.

The National Library of Wales has launched an art exhibition to mark 60 years since the flooding, showcasing the passionate protesting and lasting impact of the flooding.

Named Tryweryn 60, the exhibition is open until 14 March, and invites visitors to “reflect on what it means to lose a special place”, and why such losses continue to resonate today.