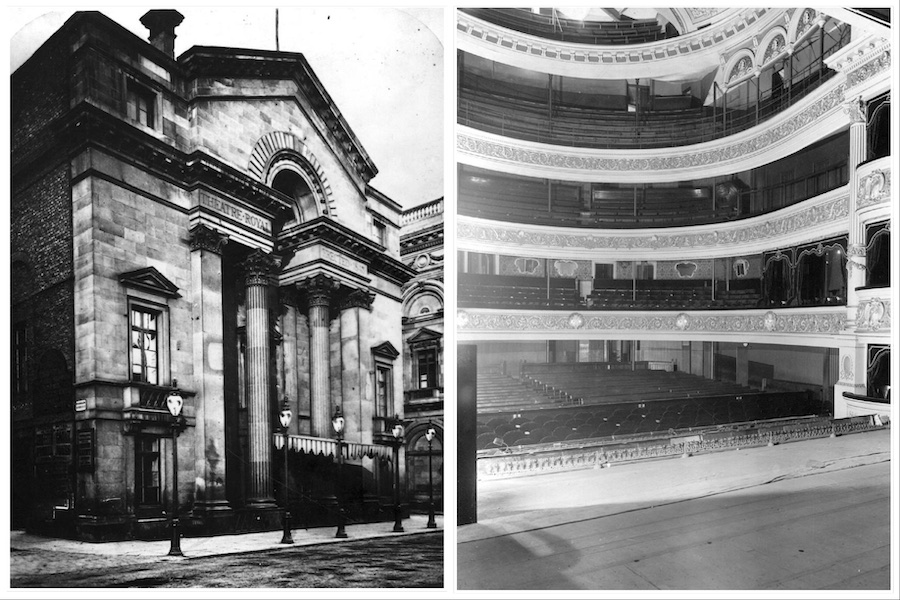

Manchester’s Peter Street has long been a cultural artery. Between the grandeur of the Free Trade Hall and the bustle of Deansgate, one neoclassical building still broods behind boarded doors and fading memories: the Theatre Royal.

Built in 1845, it is the city’s oldest surviving theatre, a once-proud landmark that has worn many masks: stage, cinema, bingo hall, nightclub, and now (mainly) silence. Today it sits in limbo, waiting for a revival worthy of its past.

What’s next for Theatre Royal?

“It’s such a prime site and such a fantastic building,” said Claire Appleby, Architecture Adviser at the Theatres Trust. “It’s heartbreaking to see it sitting there vacant when there’s such a huge opportunity for it to come back into use.”

Theatre Royal as a super cinema

Theatre Royal as a super cinema

The Theatre Royal itself was a product of loss. In 1844, Manchester’s earlier Theatre Royal on Fountain Street was destroyed by fire. Local entrepreneur John Knowles seized the chance to build anew. He purchased the site of the Wellington Hotel and Concert Room, cleared it, and laid the foundation stone in December that same year. By September 1845, astonishingly fast for a project of such scale, the new theatre was open.

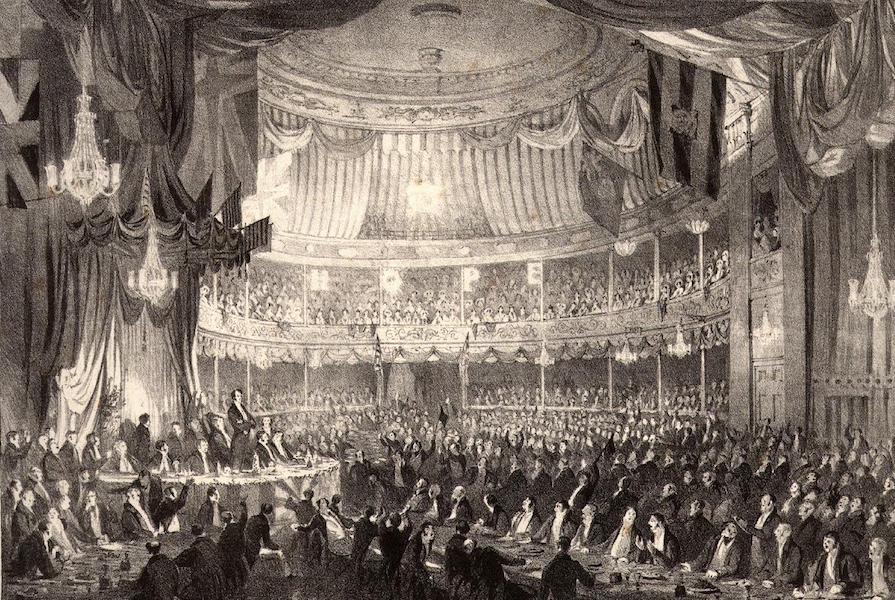

The Illustrated London News marvelled at the speed and ambition: half a million bricks laid, costs of £22,000 shouldered, and an opening night thronged with more than 2,100 spectators watching Douglas Jerrold’s comedy Time Works Wonders.

“The Theatre Royal was an Italianate marvel”

Designed by architects John Gould Irwin and Francis Chester, the Theatre Royal was an Italianate marvel. Its façade, with Corinthian columns and a commanding loggia, rivalled Europe’s finest playhouses. The horseshoe-shaped auditorium, gilded in gold and white and crowned with a vast chandelier, seated more than 2,100, dwarfing most rivals.

“The history of its architecture alone makes it significant,” Claire noted. “You’ve got this beautiful classical façade from 1845, and behind it layers of history in the interior. Each period left its mark, but the essence of the theatre is still there.”

Back when Theatre Royal was a theatre

Back when Theatre Royal was a theatre

For decades, it was Manchester’s premier stage. Shakespearean giants Henry Irving and Edwin Booth performed here. Opera seasons filled the air with Verdi and Donizetti. In 1873, American tragedienne Genevieve Ward made her debut as Lady Macbeth.

The Royal was a restless building. A major redecoration in 1861 brought gilded ornament and crimson upholstery. In 1877, architect Edward Salomons added lighter décor and new lighting. By 1889, another facelift had given it a Louis XVI ceiling painted with portraits of acting luminaries like Garrick and Kean.

But the 20th century was less forgiving. The rise of cinema changed everything. In 1922, the Royal was gutted and remodelled as a “super-cinema,” seating 2,500 and fitted with the latest projection technology. One balcony was removed, the stage was mostly dismantled, and the focus shifted to film spectacle.

“Like so many theatres across the UK, it adapted to survive,” said Claire. “You see this pattern again and again, from theatre, to cinema, to bingo, to nightclub. Each generation reimagines the building for its own entertainment culture.”

By the 1970s, cinema itself was waning. The Royal became a bingo hall, its ornate proscenium hidden but not destroyed. Then came its most notorious incarnation: the nightclub Discotheque Royale.

Hitman and Her at Discotheque Royal

In 1989, Manchester was the epicentre of clubland. The Haçienda ruled the underground, but Royales, as everyone called it, offered something glitzier.

First Leisure Corporation, owners of Blackpool Tower, spent £3.5 million restoring the interior, polishing plasterwork and stone carvings while adding chandeliers, cherub statues, and a computerised lighting rig. Thousands of clubbers poured in at weekends. Celebrity regulars rubbed shoulders with students.

It hosted cult nights like Love Train, DJ Brutus Gold’s tongue-in-cheek disco party, and even served as a TV set: ITV’s The Hitman and Her filmed here in 1990, with Michaela Strachan and Pete Waterman capturing sweaty nightlife and broadcasting the first televised performance of a boyband called Take That.

Later incarnations tried to recapture the magic, Infinity, M-Two, Coliseum, but by the 2000s, its plush glamour felt dated. In 2009, the doors closed once more.

In 2012, Edwardian Hotels London, owners of the adjacent Free Trade Hall hotel, bought the Theatre Royal. For more than a decade, it has remained shut.

“They’ve never really made clear their plans for it,” Claire explained. “At one stage, they were using it as storage and a kind of carpentry workshop. On the one hand, that keeps someone checking in on the building, but it’s not ideal. We’d love to see it brought back as a theatre.”

In 2013, the Theatres Trust placed it on its Theatres at Risk Register. “It had been closed for several years, its use was uncertain, and yet it had real potential to return as an active part of the cultural scene. That uncertainty, combined with the risks of a vacant building, meant it needed protecting,” Appleby said.

The Royal is not derelict, but time is unkind to unused theatres.

“The longer it sits vacant and unheated, the more vulnerable it becomes, to damp, water ingress, and deterioration,” Claire warned. “The owners have installed fire and security alarms, which is good, but the building is still incredibly vulnerable.”

““It feels in limbo, Such a crying shame for such a beautiful building in such a prominent location.”

Its Grade II listing means demolition is unlikely, but without investment, plasterwork, structure, and heritage features could be lost. “It feels in limbo,” Claire said. “Such a crying shame for such a beautiful building in such a prominent location.”

Some campaigners wonder if Manchester City Council could step in. Appleby is cautious but hopeful.

“We’re in frequent contact with the planning and conservation teams. They’re keeping an eye on it. When we hear concerns from the public, we pass them on. The council can push the owners to keep it in good repair, and encourage them to explore reuse.”

But she admits the hurdles are significant. “The big issue is its city-centre location. Commercially, the land is worth far more as offices or apartments. A theatre business case takes longer to pay back. That’s why Theatres Trust was set up in the 1970s: so many theatres were being demolished for more profitable uses.”

Bradford Live

Bradford Live

There are success stories. Appleby points to Bradford Odeon, now Bradford Live: “That was nearly demolished. A huge public campaign saved it. After years of passion and hard work, it’s reopened and looks spectacular.”

And in London, the Walthamstow Granada is reborn as Soho Theatre Walthamstow: “The council stepped in because they recognised its value to the high street and local economy. Together with Soho Theatre, they’ve brought it back as a thousand-seat venue. It’s fantastic.”

Soho Theatre Walthamstow

Soho Theatre Walthamstow

But the comparisons also underline the difficulty in Manchester. “City-centre sites are always tricky,” Claire said. “If you look at Theatre Royal purely through a commercial lens, the land value as a theatre is always going to be lower than as offices or apartments. But the cultural value? That’s enormous.” Despite the obstacles, Claire sees enormous potential.

“The building is structurally sound and its ornate interior survives, albeit hidden,” she explains. “It absolutely could be brought back into cultural use. The question is whether there’s the will from the owners, the council, and cultural partners.” She also emphasised the wider impact.

“Theatres play a vital role in the night-time economy. They make our towns and cities places people want to live, work, and visit. We need to make sure those uses aren’t lost.”

Campaigning to re-open the Theatre Royal

Theatre Royal Dinner, 1832

Theatre Royal Dinner, 1832

For SAVE Britain’s Heritage, the Theatre Royal represents both a risk and an opportunity.

“It’s been on our Buildings at Risk Register since 2023,” explained Lydia Franklin, Conservation Officer at Save Britain’s Heritage. “That means we’ve identified it as a building that is vulnerable but has real potential for reuse. Our role as a charity and campaign organisation is to fight for these threatened sites and advocate for their sustainable future.”

She stresses that vacancy is one of the biggest dangers for heritage. “Buildings left empty quickly deteriorate without maintenance. Damp, water ingress, and neglect take their toll, but there’s also the constant threat of demolition applications. Once a building has been allowed to fall far enough, it becomes much easier for someone to argue for flattening it. That’s why it’s crucial that the Theatre Royal doesn’t sit unused indefinitely.”

Lydia points out that the building’s Grade II-listed status should be a shield, but only if action is taken. “Listing is intended to protect and celebrate what makes a building significant. But protection is only as strong as the enforcement behind it. In this case, the listing should mean the Theatre Royal is brought back into use in a way that does justice to its heritage.”

She also emphasises the role of local people. “Communities are at the heart of our historic buildings. People form attachments through memory and daily life. That’s why they so often lead the fight to save them. But community passion needs backing, from owners, developers, councils, and statutory bodies like Historic England. Only when all of these forces align can a building truly thrive again.”

Crusader Mill, Piccadilly

Crusader Mill, Piccadilly

Nationally, SAVE’s Buildings at Risk Register lists more than 1,500 entries, showing how widespread the problem is. But Lydia is quick to highlight the other side of the story: “There are brilliant examples of reuse. In Manchester, there’s Crusader Mill, and in Bradford, Lister’s Mill, once the largest silk mill in the world, which has been transformed into hundreds of homes. Those examples prove that, with imagination and will, these buildings can be brought back into vibrant new life.”

Developers are increasingly recognising that potential. “Tim Heatley from Capital & Centric has said that enquiries about reuse projects outnumber those for new-builds by four to one. That tells you how much appetite there is. A building like the Theatre Royal could be at the heart of regeneration, creating jobs, homes, and entertainment spaces.”

For Franklin, the message is clear. “Our historic buildings are building blocks for the future. If Manchester harnesses the power of the Theatre Royal, it won’t just preserve a landmark, it will breathe new energy into the city.”

You can find out more about SAVE’s work by clicking here

Can the Council do anything to help?

When asked if the Council could intervene, officials explained that while Manchester City Council can issue Section 215 notices to force owners to keep a building in good condition, their powers are otherwise limited.

A Council spokesperson said they were “rightly proud” of Manchester’s history and stressed that the city had “a strong record of celebrating and championing our heritage” against the backdrop of two decades of rapid economic and population growth.

They pointed out that the city centre now has around 100,000 residents, compared with just a few hundred in the 1990s. This, they said, was a sign of prosperity and confidence, with people choosing to remain in Manchester thanks to employment opportunities, good housing, quality of life, and world-class attractions.

Balancing heritage with development was described as an ongoing challenge. “We believe the two can exist together,” the spokesperson said, adding that every planning application is carefully assessed both on its own merits and in terms of how it fits into the Manchester of the future.

Too often, they argued, public debate focuses on what has been lost rather than what has been saved and reused. They highlighted the Northern Quarter, NOMA, and Ancoats as areas where historic buildings had been refurbished alongside significant change, resulting in new jobs and homes.

The Council also stressed the importance of conservation areas in protecting heritage properties, noting that applications affecting such areas are given “every scrutiny available.” They said the authority works closely with developers, placing high demands on them to deliver “world-class investment” in both buildings and public spaces.

This was particularly true, the spokesperson said, in cases where buildings carry extra protections, such as the Grade II listed Theatre Royal on Peter Street. The Council aims to ensure sensitive and appropriate redevelopment, while also making sure historic properties do not fall into disrepair while awaiting investment.

Acknowledging that heritage and development in the city centre will always provoke debate, they concluded: “We take our responsibility as custodians of our city seriously, and while we often have to make difficult decisions in the ongoing balance of old and new, they are never taken lightly.”

What does the future hold for Theatre Royal?

For now, the Theatre Royal remains closed, its Corinthian façade darkened by Manchester rain, its grand staircase and gilded plaster hidden behind boarded doors.

But as Claire stresses, “It’s not too late. There’s still a real chance for the Theatre Royal to come back to life and once again be part of Manchester’s cultural scene. Seeing it sitting there unused is a crying shame, but it doesn’t have to stay that way.”

The Edwardian Hotel Group, who own Theatre Royal, refused to comment.

In theatres, when the stage is dark, a single “ghost light” is left burning. For the Theatre Royal, that ghost light has glowed for more than a decade, waiting for its next act.