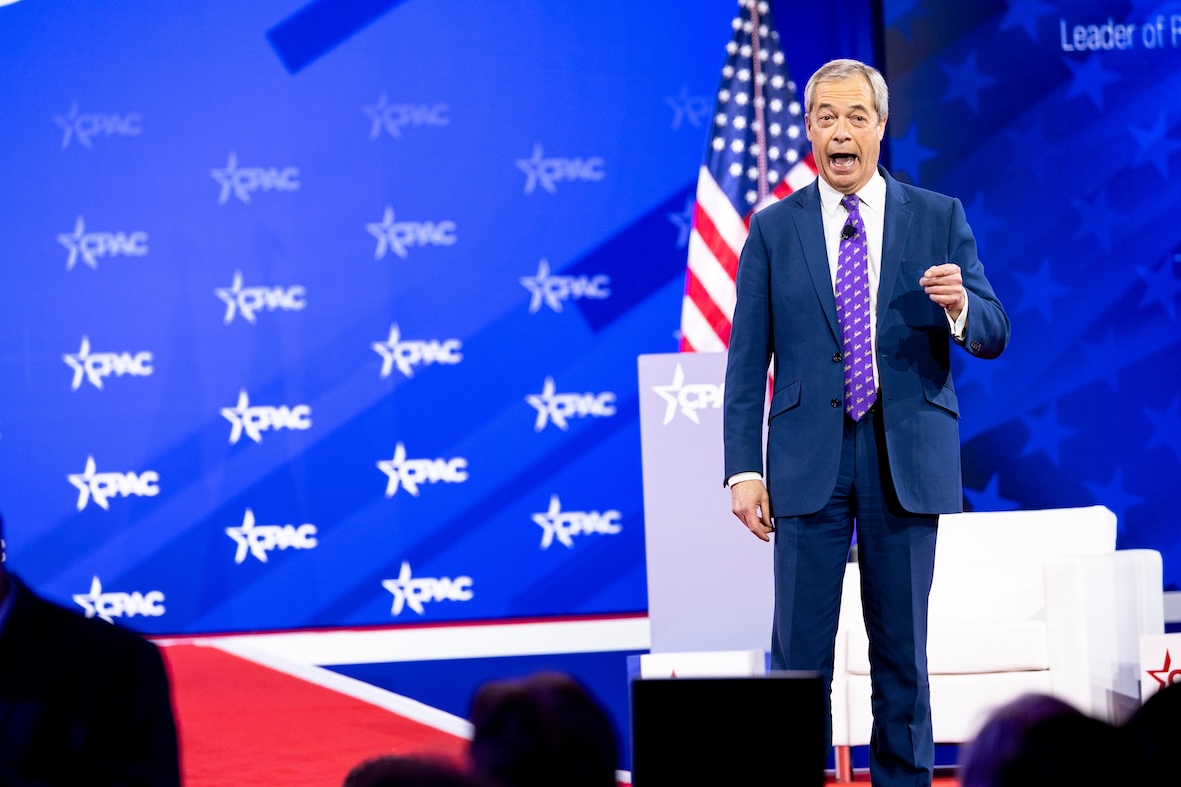

When Michael Gove proclaimed that “the people of this country have had enough of experts,” he personified the anti-intellectualism that pervaded the 2016 Referendum. Fast forward to 2025, and Nigel Farage has called net zero “the new Brexit,” while a climate change–denying think tank has sponsored an event at Reform UK’s conference titled “Is Climate Realism Inevitable?”. The hallmarks of the 2016 Referendum have been reimagined for the climate crisis. At the end of Climate Week NYC we look at how, once again, misinformation, mistrust of international institutions, and the weaponisation of national sovereignty form the backbone of Nigel Farage’s plan.

Due to the increasing unpopularity of Brexit, with almost twice as many now believing it was the wrong decision (56%) compared with those who still feel it was the right choice (31%), Nigel Farage needs a new bogeyman. More than five years after Britain left the EU, the benefits have yet to be seen, while the costs are painfully apparent: an economy £140 billion smaller, British businesses less competitive, and a country divided. It is no surprise that Farage is unusually coy about highlighting what was his defining project.

Step into the breach: net zero. Each year brings fresh evidence of the devastating effects of the climate crisis. Blazing wildfires across Europe caused around €43 billion in damage this summer alone, while droughts across Eastern and Southern Africa pushed more than 90 million people into extreme hunger. And yet, climate change is losing salience among the British public, with climate policies viewed with increasing scepticism. Three years ago, the environment was considered a greater issue facing the country than immigration. Today, almost a third (29%) of Brits think too much is spent on climate policies such as net zero, while the environment now ranks only as the seventh most important issue facing the country.

So, what has changed? The rise of populism across the globe has had disastrous consequences for climate action. Upon his election to the White House in 2016, Donald Trump withdrew the US from the Paris Accord, repeating the trick upon his re-election. Further south, former Brazilian President Jair Bolsonaro was outspoken in his criticism of climate policies. Equally dismissive of the need for climate action is Argentinian President Javier Milei, who in February threatened to follow Trump in leaving the Paris Accord.

In Europe, a similar picture emerges, as climate change has been drawn into the culture wars that have dominated the politics of the 2020s. So why is climate action so anathema to right-wing populists?

One of the causes of the rise of right-wing populism has been the dual processes of deindustrialisation and globalisation, which have created a geographical bloc of voters who feel “left behind.” Such voters were critical for the Leave vote in 2016, vital for Boris Johnson’s landslide majority in 2019, and remain influential today, with the Red Wall Labour caucus holding considerable sway over the government.

In its own way, climate policy, such as net zero, has become symbolic of these dual processes: the growing uncompetitiveness of British industry on the one hand, and the polluting nature of the new industrial powerhouses in Asia on the other. Farage, and in particular Richard Tice, have jumped on the opportunity to bemoan net zero and demonise green energy alternatives. A hypocrisy, given Tice’s 2022 claim that fitting solar panels would “save hundreds of tonnes of CO2 every year and help our occupiers with lower energy bills.”

Populism, by its very nature, offers simple solutions to complex problems, and there is no problem quite as complex as climate change. Populists have a disdain for complexity, which partly explains their distaste for academics and experts. This disdain bleeds into their outlook on climate change. As a global issue, often abstract in the minds of Brits who have not yet experienced the kind of extreme weather events that have caused misery across much of the world, populists are keen to absolve themselves of responsibility for the health of our planet. Once again, our position as an island is fostering political naïvety and brashness.

Not only is the problem of climate change complex, but so too is the solution. As the most global of global problems—as the populist right often points out—climate change requires a level of international cooperation hitherto unseen. But international cooperation comes at a cost: it requires nations to compromise on their unique interests for the greater good. As the Pandora’s box of Brexit illustrated, the populist right has a tendency to unleash the corrosive forces of nationalism when faced with any kind of crisis. However, the climate crisis(and it is precisely that) is one which cannot be solved by any single nation. The populist right acknowledges this, but they refuse to follow that reality to its logical conclusion, recognising the importance of fostering cooperation. To admit that some issues demand international collaboration would undermine the nationalist platform on which they stand. And so, those at Reform UK choose instead to undermine the very reality of climate change. It is the clearest example of party over nation, and perhaps the least patriotic act of them all.

Beyond Reform UK, because there is more to this than Nigel Farage,, lies a right-wing ecosystem that thrives on sensational populist narratives. Right wing media outlets were crucial in entrenching a sense of European Union bureaucratic overreach in the nation’s psyche. Think of the alleged EU ban on bendy bananas and other such Euromyths…

The modern media ecosystem supercharges this kind of misinformation and disinformation even more so today than in 2016. Not only do right wing media outlets have climate action in their sights, but the creation of GB News and the descent of social media platforms like X into radicalising echo chambers—with limited accountability or monitoring—make the job of the right-wing populist even easier than it was a decade ago. High levels of mistrust among the British public toward politicians and the media also create fertile ground for the spread of myths and conspiracy theories both on- and offline. Whereas Michael Gove once said the British public had had enough of experts, in 2025 it might be more accurate to say they have had enough of everyone.

And there you have it, a global issue that relies on international cooperation, compromise, and the delegation of sovereignty. A complex, abstract problem that allows populists to frame climate action as simply the next chapter in a historical process that has disadvantaged and deindustrialised communities now more vulnerable to nationalist messaging. An issue even more exposed to misinformation than Brexit, thanks to the transformation of the media landscape in the 2020s. For Farage, Brexit is the past; weaponising climate action as the next frontier of the culture wars is the new vogue.

The ultimate irony is that Reform UK’s disdain for effective action on climate change will only worsen the problems on which they campaign. Billions of pounds in relief funds for increased flooding and damage to national infrastructure will only worsen our national debt. Climate change is also predicted to cause the greatest human migration crisis in history as parts of the globe become uninhabitable. A failure to deal with the climate crisis is not just morally reprehensible but economically illiterate.