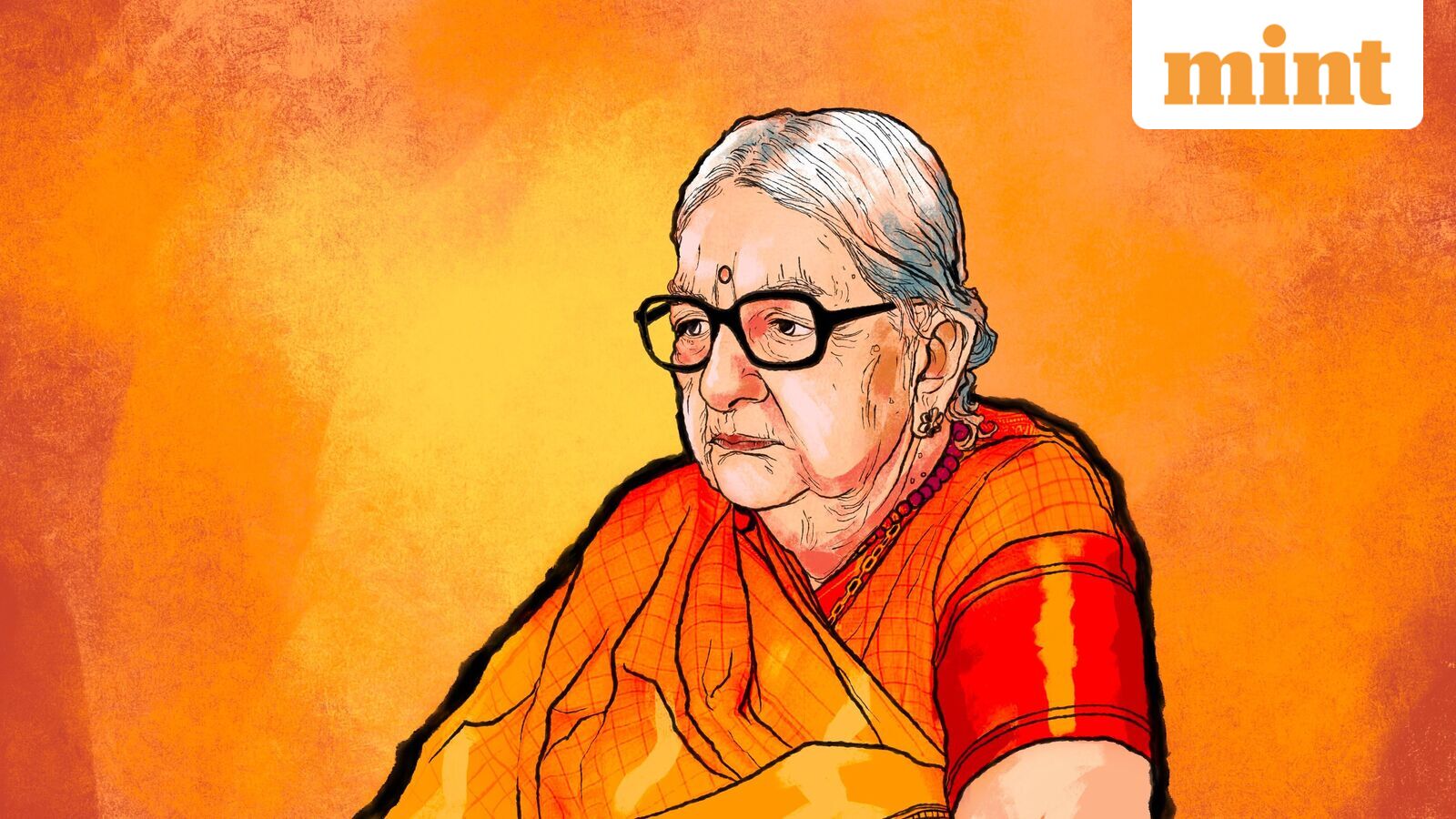

But this diminutive woman was one of India’s boldest builders of social enterprise, long before the term existed. Her vision that real freedom lay in self-reliance and economic agency seeded institutions, livelihoods, and entire ecosystems that are shaping lives even today.

Much has been said about her courage.

There’s the now-famous story from the horrifying weeks of partition, when, seeing a tide of desperate refugees pouring into Delhi, Kamaladevi stormed government offices and demanded action. If not, she warned, she’d lead a protest straight into bureaucratic sanctums. The impasse broke overnight. By morning, India’s first cooperative township in Faridabad had official sanction.

Change, for her, was never something to request politely. It was something to demand and wrest from the jaws of officialdom.

Freedom fighter

Born in 1903 in Mangaluru, Kamaladevi stepped into public life already primed for rebellion. Her childhood, shaped by Girijabai, her fiercely progressive mother, was a crucible of radical ideas, feminist thought, and social critique. That meant she was never going to meet the docile expectations of upper-caste womanhood in colonial India.

Marriage at 14 and widowhood by 16 would have consigned most young women of her time to the margins. Instead, she shattered conventions once more by marrying the poet, actor, and revolutionary Harindranath Chattopadhyay.

Her intellectual and political learning gathered steam at Bedford College in London, where she studied sociology and honed an argumentative, unflinching wit.

Not surprisingly, her entry onto the national stage was neither polite nor peripheral. In 1930, she confronted the Mahatma himself. Why, she asked, should only men lead acts of civil disobedience? Gandhi saw the wisdom in her words and the steel in her soul and made her an integral part of the Salt Satyagraha.

Social entrepreneur

But Kamaladevi wasn’t content with fighting the oppressors. She believed that the real work began after political freedom. She saw nation-building in terms of freedom from poverty, especially for women, artisans, and the displaced.

Indeed, the partition turned her into a social entrepreneur from a freedom fighter as she envisioned regeneration through cooperative townships, vocational training, and income-generation schemes.

What most defined Kamaladevi, though, was her phenomenal grasp of culture’s economic and social power. Where the British had industrialized and homogenized crafts, she saw the value of India’s handloom, pottery, embroidery, and folk traditions, not as nostalgia, but as identity reclaimed.

In his book, Kamaladevi Chattopadhyay: The Art of Freedom, author Nico Slate wrote how she lamented the fact that “the children of the people that created the wonderful works of art at Polonnaruwa and Anuradhapura are today feeding their hungry souls on Dunlop tyre advertisements and match labels that adorn the walls of the huts in the villages.”

To that end, she founded the All India Handicrafts Board and the Crafts Council of India, embedding artisan welfare into the very scaffolding of independent India. At the same time, she institutionalized training, ensured government procurement of handmade goods, and introduced national awards for craftspeople.

Her belief in art as activism flowered in institutions like the Institute of Kathak and Choreography (NIKC) in Bengaluru, which she helped set up. She also seeded organizations that would become the Sangeet Natak Akademi, the National School of Drama, and the Dolls Museum in Delhi.

The legacy

It is instructive to compare Kamaladevi’s expansive, mission-driven legacy to today’s curated heritage startups. Over the last 25 years, a burst of urban brands, design houses, and venture capital-backed e-commerce outfits has commodified handicrafts as fashionable lifestyle products.

Artisan stories are pressed into Instagram narratives and fair trade labels. Yet, rarely do the men and women who peddle these brands match Kamaladevi’s devotion to rural empowerment, real leadership from within communities, or long-term sustainability.

Many for-profit ventures, motivated by profits and market trends, treat the artisan as a supplier at the tail end of the value chain rather than a co-author. Where Kamaladevi fought for legal and social transformation, today’s industry is driven by branding, public relations, and margins.

The many honours she received—the Padma Bhushan, the Padma Vibhushan, the Ramon Magsaysay Award, and the UNESCO Award—barely begin to capture the magnitude of her contribution.

She passed away on 29 October 1988, leaving behind institutions that continue her work. Today, when an artisan in India signs their name to a piece of work, when cooperatives negotiate fair wages, and when craft forms survive globalization’s tide, Kamaladevi’s invisible hand is at work.

For more such stories, read The Enterprising Indian: Stories From India Inc News.