This weekend, Oxford’s Sheldonian Theatre, a baroque jewel which usually hosts choral recitals and academic pageantry, will welcome a different kind of congregation. More than a thousand people are descending on the city for Transform Trauma Oxford 2025, billed as Europe’s largest trauma conference.

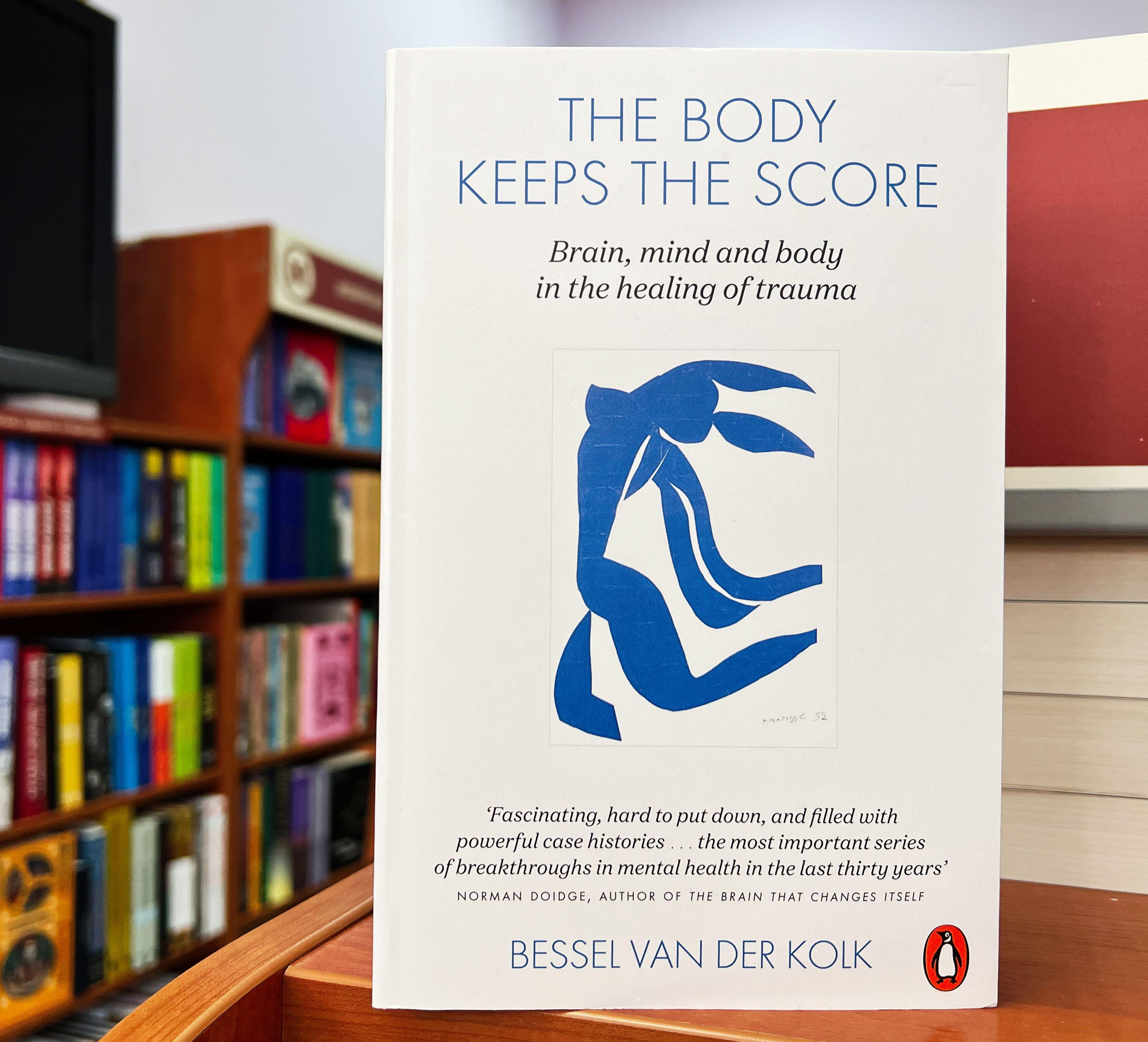

Across three days, the crowd, made up of clinicians, therapists and campaigners who will have paid £900 for the privilege, will listen to talks from Bessel van der Kolk, a Dutch psychiatrist whose book The Body Keeps the Score has become a publishing phenomenon, as well as the American psychotherapist Esther Perel and Alanis Morissette, the singer-songwriter who has spoken movingly about her own experience of sexual assault and now campaigns on trauma and mental health.

This line-up, which feels as much like a cultural festival as a clinical conference, shows how far the concept of trauma has travelled; from a niche diagnosis, largely reserved for war veterans and survivors of sexual assault, to a cultural touchpoint, the lingua franca of the internet and a multibillion-dollar industry. How this has happened is a question that the Scottish writer Darren McGarvey interrogates in his new book, Trauma Industrial Complex: How Oversharing Became a Product in a Digital World.

‘I was dining out on grief’

Darren McGarvey, 41

SUNDAY TIMES PHOTOGRAPHER JAMES GLOSSOP

McGarvey, 41, a writer and broadcaster who raps under the name Loki, has first-hand experience of the way in which trauma can be repackaged as cultural capital in the digital age. In 2018 his memoir, Poverty Safari, an account of childhood hardship and addiction growing up in Glasgow, won the Orwell prize and McGarvey became an overnight star of the literary scene with invitations to give keynote speeches and appear on television. His personal story became a kind of calling card — and a currency that guaranteed bookings.

Looking back, he admits he was “dining out on grief”, using his past as both validation and leverage. But the same story that brought him work and acclaim also became a trap. Becoming a poster boy for childhood trauma put him in a narrative straitjacket that left little room for healing or growth.

At one point on his book tour, he was even given a “drive-by” diagnosis of attention deficit disorder (ADD) by Gabor Maté, the Hungarian-Canadian physician and trauma expert who made headlines in 2023 when he offered Prince Harry a similar assessment during a livestreamed therapy session:

At the time, McGarvey felt that the validation was electrifying. “How awesome is that?” he writes, wryly, in his new book. “The king of trauma discourse himself offered me a possible neurodivergent label just as neurodivergence approached the very apex of its trendiness.” Now, though, he’s not so sure. Picking up a new label, he explains, reaffirmed his victimhood and gave him extra cachet to trade off. But it was a “self-deception” which stopped him from engaging with the truth.

With the publication of Trauma Industrial Complex, McGarvey joins a growing tide of authors, clinicians and researchers who are concerned about the direction of travel: over the past two decades, trauma has ballooned from a clinical term into a cultural shorthand for almost any form of suffering.

The concept of trauma itself has a long history in psychotherapy. Sigmund Freud first used the term in the 1890s in relation to “hysteria”, linking symptoms in women to repressed memories of childhood abuse. After the World Wars, the suffering of soldiers was variously described as “shell shock” and later “combat fatigue”, precursors to what became known as post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). It was only in 1980 that PTSD was formally recognised in the American Psychiatric Association’s Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, followed by the World Health Organisation in 1992. It was originally framed around extreme events such as war, sexual assault or natural disaster.

This is still the way trauma is described in diagnostic manuals today. PTSD refers to a persistent cluster of symptoms like flashbacks, disturbed sleep and hypervigilance which tend to last for at least a month and seriously disrupt daily life. It’s generally treated with trauma-focused therapies such as cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) and EMDR (eye movement desensitisation and reprocessing), sometimes supported by antidepressant medication.

Gone in 60 seconds?

A quick scroll through the trauma hashtag on TikTok, however, brings up more than 14 billion videos, many from mental health influencers and therapists promising to “break down trauma in 60 seconds” or offering “three signs you’re traumatised without even realising it”. Trauma titans like Maté and Van der Kolk are household names. The latter’s 2014 book, The Body Keeps the Score, argued that trauma embeds itself in the body’s neurobiology, reshaping memory, immunity and even posture, and is now one of the most successful nonfiction titles of all time, spending almost seven years on the New York Times bestseller list.

A whole “trauma economy” has sprung up around this appetite. Selena Gomez, for example, launched her mental-health start-up Wondermind in 2022, backed by venture capital and valued at $100 million, positioning her own struggles with anxiety and bipolar disorder at the centre of its brand. This is part of a wider trend in which personal disclosure doubles as both testimony and business model. Nowadays, the financial incentives to exposing your life’s challenges can be significant. Sara McCorquodale, the chief executive and founder of CORQ, an influencer intelligence and trend forecasting platform, says: “We’ve seen it happen over and over again: an influencer shares a really harrowing experience, it often drives huge engagement and rapid growth on their platform and that, in turn, makes them far more commercially attractive to brands.”

In a 2024 academic paper, Lucy Britt and Wilson H Hammett argue that trauma narratives can be appropriated to manipulate perceptions, particularly by those already in positions of privilege. They highlight the case of Brock Turner, a Stanford swimmer convicted in 2016 of sexually assaulting an unconscious woman, who appealed to the judge for leniency by describing how traumatic the aftermath of his arrest had been. Turner’s statement positioned him as a secondary victim of the crime, one whose future hung in the balance.

Within a clinical setting, there have been rumblings for some years about trauma’s “concept creep” — the steady widening of the term beyond its original definition in psychiatry — to encompass an ever-expanding range of experiences and everyday stresses. The theory that trauma fundamentally disrupts our neurobiology, as put forward by Van der Kolk, has been viscerally disputed. “The idea that everyone is traumatised and that trauma lives on and on in the body suits the therapy world very well,” says George Bonanno, professor of clinical psychology at Columbia University. “It fits the business model.”

In 2021 he wrote a book called The End of Trauma: How the New Science of Resilience is Changing How We Think About PTSD. “I teach a very large course on trauma every year, and students come to the class completely expecting that everyone is traumatised — it’s a very pervasive idea now.” He admits that the vast majority of us have been exposed to at least one but probably more traumatic events in our lives. Car accidents, violence, medical emergencies — “these are ubiquitous. But in fact, most of the data shows very clearly, and this is my research area in particular, that the vast majority of people do not experience lasting harm. They do not develop PTSD. They actually show a resilience pattern”.

‘People will call just about anything trauma’

Michael Scheeringa is a retired child psychiatrist who studied stress and trauma for almost 30 years and up until 2023 was a professor at Tulane University School of Medicine. Last year he published a book called The Body Does Not Keep the Score: How Popular Beliefs about Trauma are Wrong as a corrective to what he sees as an all-too-pervasive narrative.“I was one of those people who was trying to find a neurobiological consequence of trauma. I did heartrate studies, cortisol studies, and I wanted to find that trauma was causing some kind of temporary or permanent damage. But my research wasn’t finding it. And as I was looking at everybody else’s research, they weren’t finding it either.”

He argues that the current trauma discourse comes down toleft-wing ideology. He says: “I’m conservative … and since 2020 scholarship has been blossoming like weeds about racial discrimination, transgender discrimination, LGBTQ discrimination, [arguing that] those are all traumas. Now, in the literature, there’s hundreds of papers written about that, but there’s absolutely nothing life-threatening or traumatic about those things.”

Too often, he argues, trauma is a label that offers an easy way out. “People will call just about anything trauma because it gives them a sense that there’s a single reason for their problems. It means they don’t have to look within themselves.”