The UK and EU are set for a temporary deal to stop British businesses being badly harmed by a new tax on energy that threatens to drive up bills and hit jobs and growth.

The EU’s new carbon border tax (CBAM) is being introduced from 1 January, meaning British businesses will be hit by levies on exports to Europe, which are produced using polluting energy-intensive methods.

But amid industry warnings that the tax would push up consumer bills and leave UK exporters with an £800m bill of payments to the EU, the two sides look set for a deal to help British businesses – and households – dodge the worst of the levy.

New FeatureIn ShortQuick Stories. Same trusted journalism.

The i Paper understands that a temporary fix is now viewed as likely on both sides because London and Brussels are anyway thrashing out a wider deal on emissions trading that will solve the problem permanently as part of the Brexit reset, but which is expected to take months.

It comes as both sides begin to plan for the second Brexit reset summit to be held in May or June next year, where final deals could be reached on food and drink trade, youth mobility and other areas.

An agreement for the UK to join Brussels’ new €150bn (£130m) rearmament fund to boost European security is also expected to be agreed by mid-November, despite attempts by some EU member states such as France to impose tough conditions on British participation.

Border tax remains urgent problem

The EU carbon border tax remains an urgent problem though as it will be introduced on 1 January.

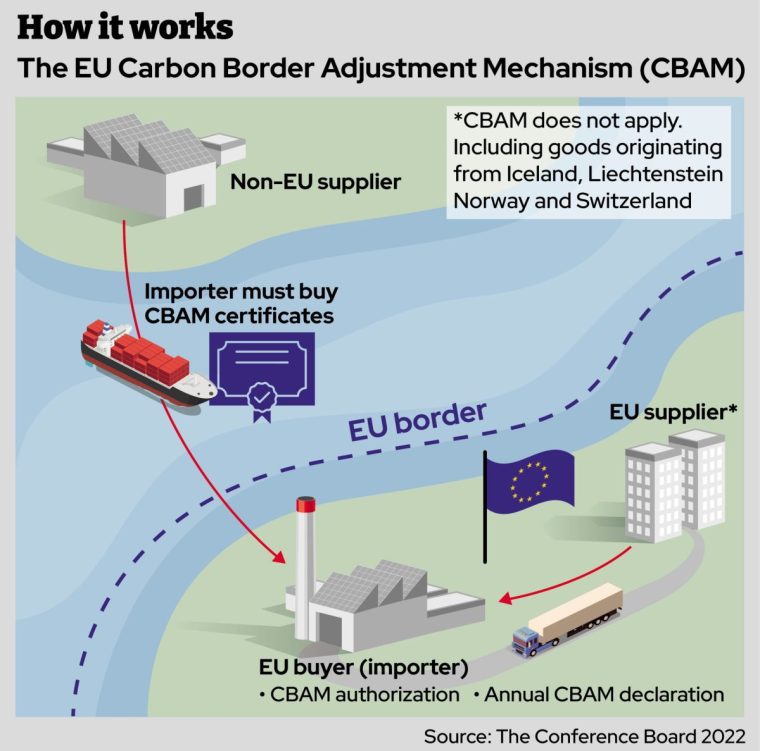

It is designed to encourage greener production, and level the playing field as EU companies already pay for emissions through a trading scheme. The levy is to prevent imports of energy-intensive products such as steel, from countries which have weaker environmental legislation undercutting EU companies, or to stop companies relocating to places with weaker rules.

Any exemption would only need to last a matter of months while the two sides thrash out a wider deal on linking the UK and EU emissions trading systems (ETS), which was pledged as part of the UK-EU Brexit reset summit in May.

How the carbon tax works

How the carbon tax works

The ETS sees a cap placed on the carbon a company or airline can emit alongside a trading system of allowances.

The i Paper has been told that EU relations minister Nick Thomas-Symonds will this autumn ask Brussels for a temporary exemption from its carbon border tax, with Rachel Reeves believed to be concerned about the potential impact on UK firms.

A formal exemption is likely to be rebuffed by Brussels as the legislation on the tax does not allow for it.

However, there is a willingness and belief in the EU that it will be able to find a way around the law and reduce the impact for British businesses while a wider deal is agreed.

How tax would impact UK firms

There are two ways the EU carbon border tax could impact UK firms.

Firstly, British businesses will need to pay the difference between the higher EU emissions trading price and the UK price when they export to the continent.

Secondly, even if this does not apply because the prices are the same, or the UK price is higher, there is a complex non-tariff barrier for British exporters as they will need to work out the carbon content of their products and get it independently verified and audited, creating red tape.

There are also complications for Northern Ireland, which is effectively in the EU’s single market for goods, over which carbon border tax would apply and the danger of placing a new regulatory border on the island of Ireland.

Adam Berman, director of policy at Energy UK, said: “It’s in the interests of both sides that a solution can be found before 1 January.

“Without a solution in place to exempt the UK from the CBAM during linkage negotiations, the design of the EU CBAM will result in higher energy bills and higher emissions in Northern Europe.

“This would be a bizarrely perverse outcome for a mechanism designed to mitigate climate change and strengthen the EU’s competitiveness.

“The outcome for Northern Ireland would also be problematic.

“It would be surprising if the European Commission isn’t aware of the political consequences of putting in place a new regulatory border on the island of Ireland and its implications for the Windsor Framework.”

David Henig, UK director of the European Centre for International Political Economy, said the two sides were working on temporary “mechanisms” to avoid British firms being hit by the carbon border tax, and that there were solutions “in the technical detail”.

“Work is under way, there is a feeling that Northern Ireland needs a solution, for the rest of the UK this might be more difficult, not least while the EU is working out its overall implementation,” he added.

A UK Government spokeswoman said: “We aren’t going to provide a running commentary on negotiations.”