One of the charming aspects of following foreign football is realising that certain concepts are expressed in different ways to how it’s done in your own country. And one of these, for those of us accustomed to British conventions but who follow the game in continental Europe, is the simple passage of time.

So whereas you’re generally more likely to find the 24-hour clock on the continent — a kick-off time might be listed at “19h” — it is somehow also more common for their television scoreboards to display a clock counting up from 00:00 at the start of the second half, rather than the 45:00 we’d be accustomed to in Britain. Similarly, if you read — for example — La Gazzetta dello Sport in Italy, you won’t read goals recorded as being scored in the 65th minute in its pages, but instead in the 20th minute of the second half.

Another example is how generations of talent are spoken about.

In Barcelona, for example, mention the “Generación del ’87”, and people know what you mean: the ultra-talented group of players who came through Barca’s La Masia academy that featured Gerard Pique, Cesc Fabregas and Lionel Messi, all born in 1987.

Cross the border into France and say “La generation ’87”, and you’re referring to the likes of Karim Benzema, Hatem Ben Arfa and Samir Nasri for the same reason. In fact, in some countries, age is expressed by the birth year, as much as by how many years you’ve actually been alive. But, off the top of your head, do you know which England players were born in 1987? Probably not. You never have much cause to consider it.

In Britain, we don’t really refer to footballers by their year of birth — perhaps partly because young players are usually grouped according to their academic year, which runs from September to the following August. And the closest equivalent generation to Barcelona’s of 1987 is Manchester United’s “Class of ’92”, which refers to the year those players progressed from youth level to the first team, rather than when they were born.

Yet, at the same time, few other countries’ recent football fortunes have been so dominated by talk of a particular era of players.

Even now, when England have reached two major tournament finals in the last half-decade, there’s still an obsession with the so-called golden generation of 20 years earlier.

‘Action’ from an 1878 game between England and Scotland (Hulton Archive/Getty Images)

So here’s an attempt to look at precisely which generations — and, to be more specific, which years — have been most profitable for the England national team in terms of appearances, all the way from 1831-born Alec Morten, to Myles Lewis-Skelly, who is — to use a continental expression — an ’06.

First things first — 1831 is a ludicrously early start date here, considering England didn’t play their first international until 1872. But Morten played for England as a goalkeeper the following year, making his debut — and indeed his final appearance — at the age of 41. He’s the oldest-ever England debutant, and was such an anomaly that despite being born at the start of the 1830s, no other player from ‘his’ decade represented England.

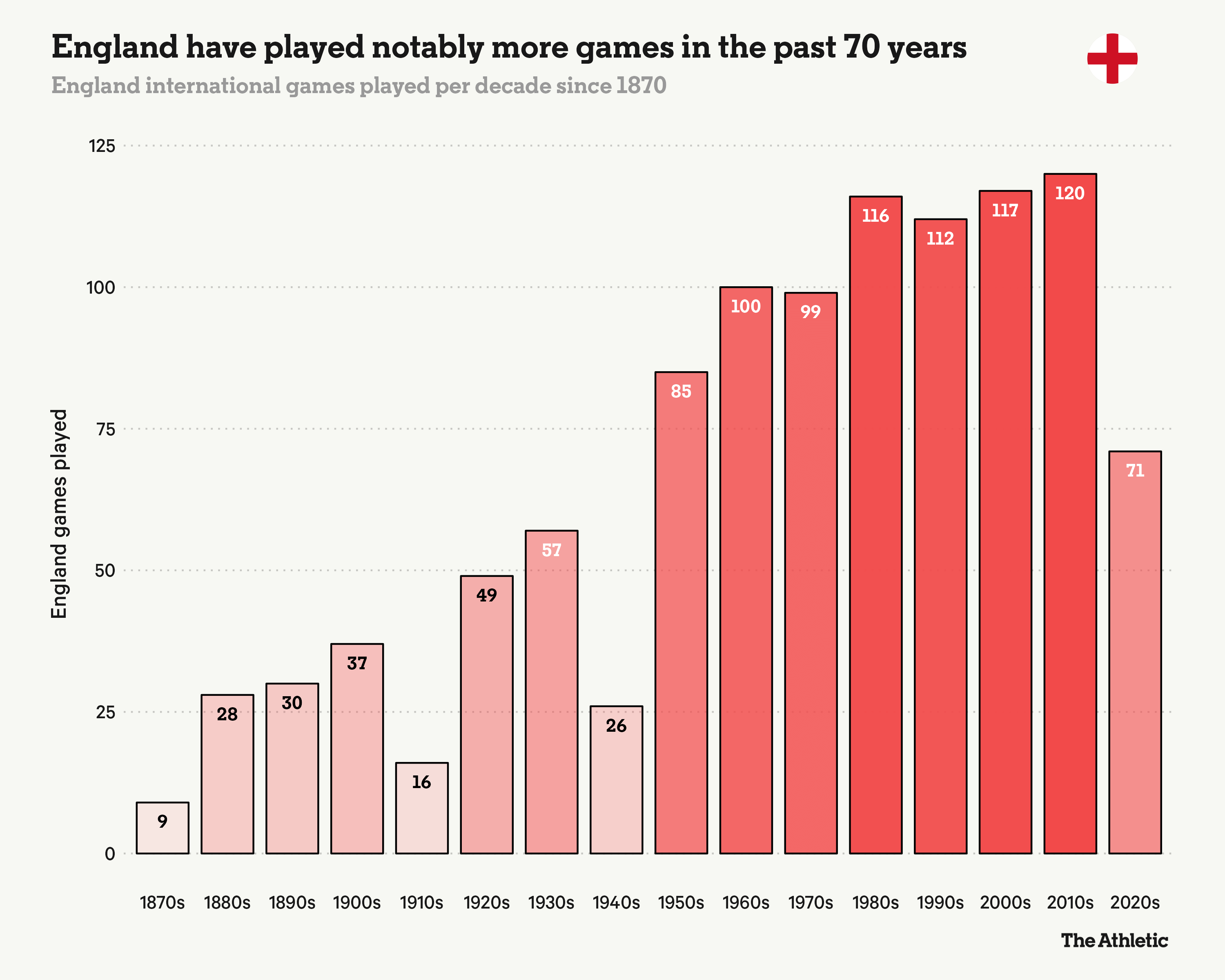

Before we get into the specifics about caps won, we need to consider a couple of key points. It’s impossible to ignore the fact that England started playing matches much more regularly from midway through the 20th century, and therefore comparing numbers from before that point isn’t worthwhile. Since the 1980s, the number of games played per decade has been relatively consistent.

It’s also important to consider how the number of births per year has fluctuated over the period we’re looking at. The Office for National Statistics data below is for the United Kingdom overall, rather than simply England. But we can trust the overall pattern here, which in the 20th century is marked by a couple of obvious spikes just after the two world wars, and another in the mid-1960s.

Clearly, there’s going to be a roughly 25-year lag when it comes to winning caps for England.

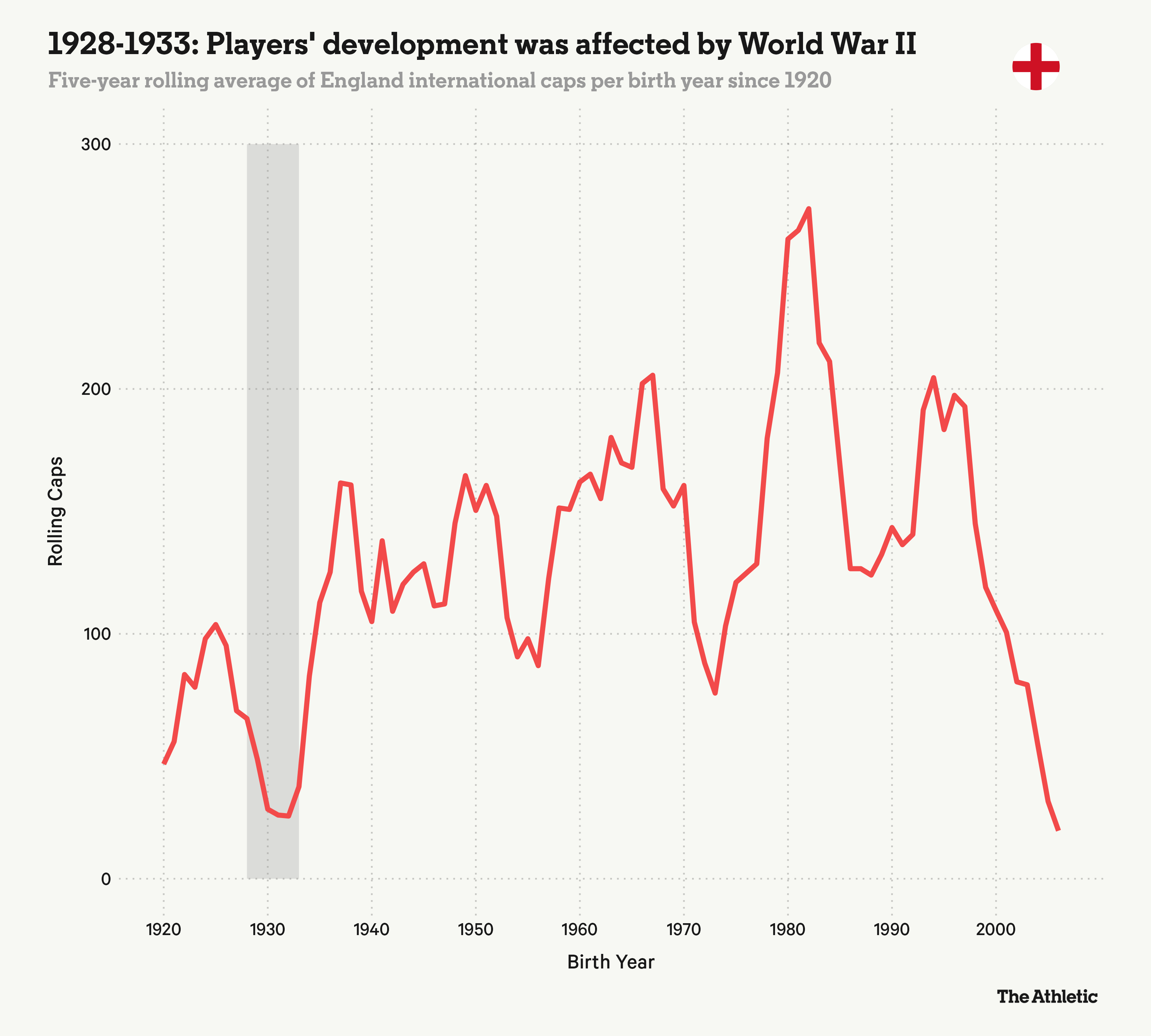

The first trend is the significant dip roughly a century ago.

This is very interesting, because you’d expect a war-related dip at some point in this chart. But the dip doesn’t come in the wartime periods of 1914-18 or 1939-45, when the birth rate was low. In fact, those periods produced some of England’s most celebrated — and capped — players, with Stanley Matthews born during the First World War (1915) and the likes of Bobby Moore and Geoff Hurst during the Second World War (both 1941).

Bobby Moore, born in 1941, pictured in August 1959 (Evening Standard/Hulton Archive/Getty Images)

And the noticeable dips also don’t come for the generations of players who would be expecting to play their peak years for England during wartime either — note the lack of games in the 1940s in the earlier graph.

Instead, the noticeable dip comes around 1930. Presumably, this is because those players lost their ‘development’ period — their early teenage years — to the war. The most famous England international born during this period is actually more notable for his time as manager: Bobby Robson (1933).

His generation got largely overlooked when they were in their peak periods, because players born later in the 1930s “only” had their childhood years affected by the war, but, crucially, not their teens — that’s the spike we see here, which provided the likes of Bobby Charlton, Gordon Banks (both 1937) and Roger Hunt (1938).

The subsequent brief spike represents the boomers born just after the Second World War. Clearly, this correlates nearly with the birth rate exploding; 16 players born in 1948 represented England, including Ray Clemence and Trevor Brooking, the highest figure for any single year since 1901. It wasn’t an outstanding generation, but there were certainly lots of options.

The next pronounced spike came in the mid-1960s — roughly around the time of England’s World Cup win on home soil, and comprises largely those who would play a major role in England’s Euro 96 campaign. Stuart Pearce (1962), David Seaman (1963) and Tony Adams (1966) were born in that period.

Tony Adams, left, and Stuart Pearce, born in 1966 and 1962 respectively (Laurence Griffiths/ALLSPORT)

What happened next? Why the sudden fall in the 1970s? Well, maybe we have to scroll up and look at the birth rate again — and remember that during this period it fell about 33 per cent from its post-war peak.

There simply weren’t many people born in the first few years of the 1970s. Granted, 1970 itself provided Alan Shearer, Gareth Southgate and David James, who all played more than 50 times for England. Those born just afterwards — Steve McManaman, Darren Anderton (both 1972), Jamie Redknapp (1973) — made 37, 30 and 17 international appearances respectively, much fewer than their talent would have suggested, for various reasons.

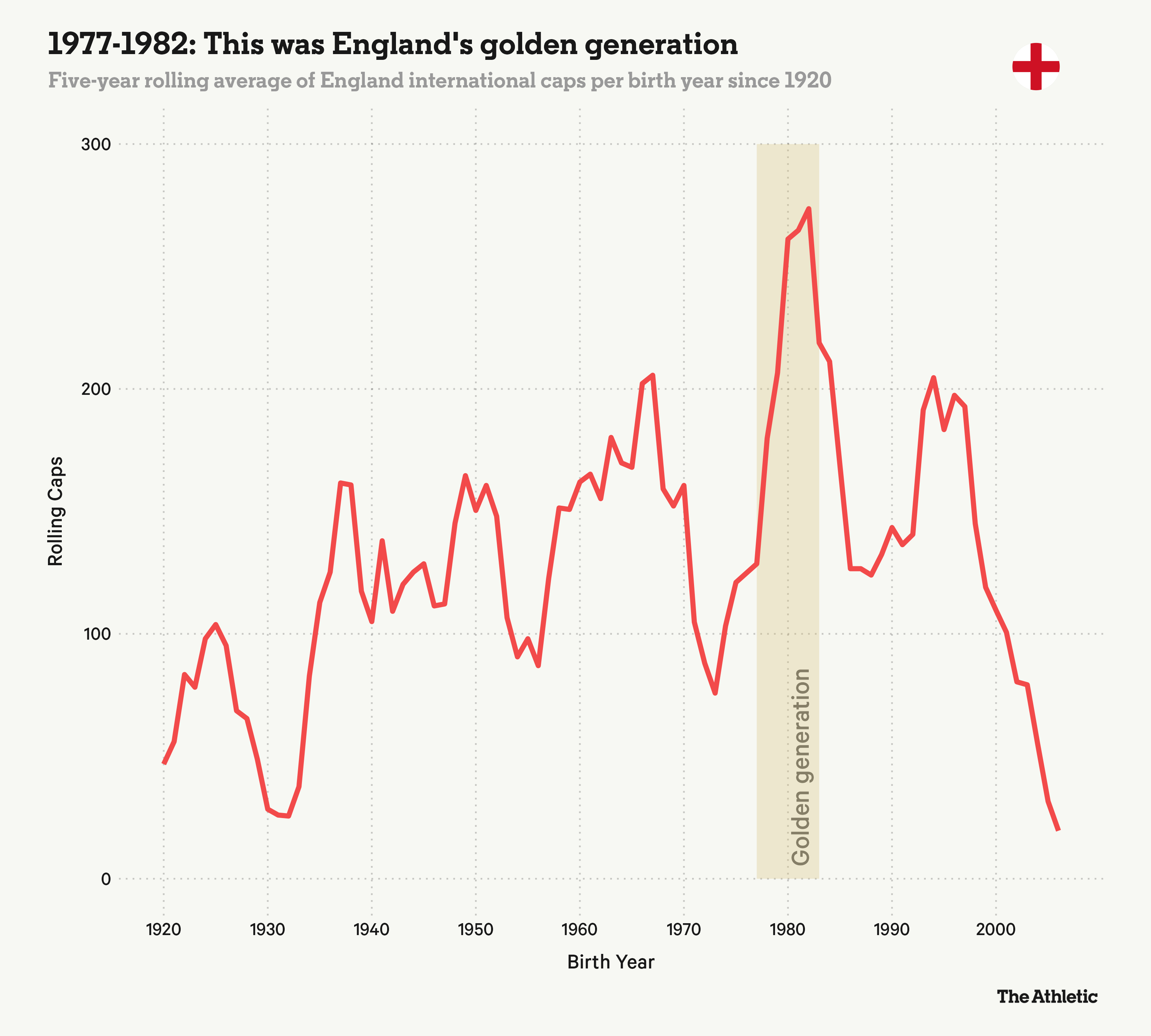

Next, there’s a massive spike. We all know what this is.

But hang on a minute! Because something very strange happens here.

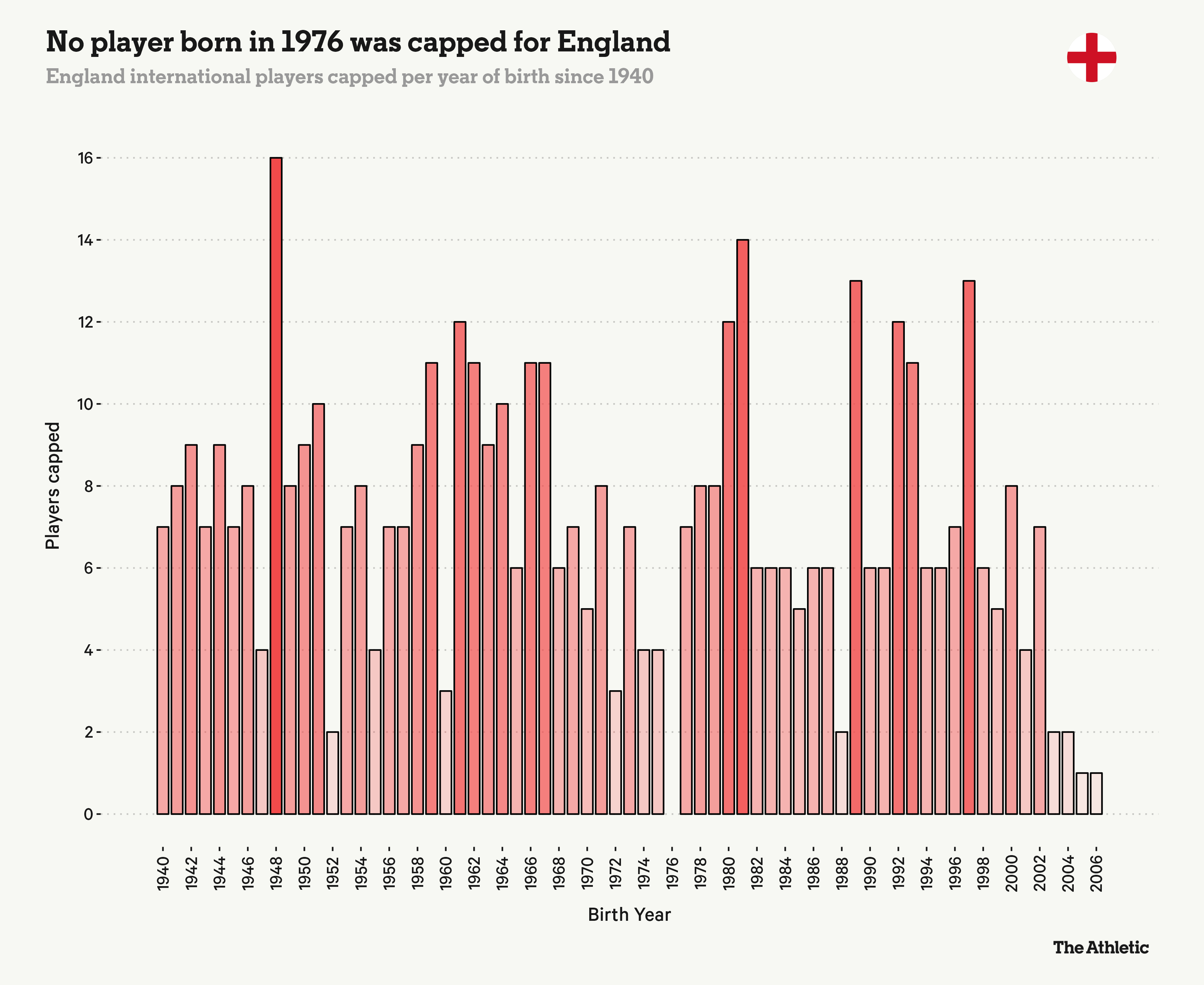

To those of you turning 50 next year: firstly, commiserations. Secondly, why were you lot so bad at football? For some reason, not a single 1976-born player ever represented England. It’s the only year of the entire 20th century that failed to contribute even one.

The previous year had produced David Beckham, Gary Neville and Nicky Butt, and 1977 had Phil Neville (just three weeks in) and, well, Danny Mills. But 1976 had nobody — and not even anybody, in fairness, who can feel particularly ‘robbed’ of an England cap.

Stephen Hughes, the midfielder who made some crucial contributions to Arsenal’s 1997-98 double-winning campaign, was probably the most promising 1976-er at youth level. Otherwise, that year offered almost nothing (which is particularly damning given 1976 was a leap year, and therefore had a 0.3 per cent advantage over most other years).

Stephen Hughes – the best of England’s 1976 crop? (Ben Radford /Allsport)

Of course, this fallow year came during the ‘golden generation’ period. There’s no official start and end date for this, but let’s take it from 1975, and the aforementioned trio of Manchester United players in Beckham, Gary Neville and Butt, through to the close of 1980. That period takes into account John Terry, Rio Ferdinand, Ashley Cole, Steven Gerrard, Frank Lampard and Michael Owen.

It’s no surprise that this is the most noticeable point on the rolling caps graph, although it must be acknowledged that this generation also benefited from a higher-than-ever number of caps being dished out, thanks to then manager Sven-Goran Eriksson’s fondness for making 11 substitutions in friendlies, most notably changing his entire XI during a 3-1 home defeat to Australia in 2003. A year later, world football’s governing body FIFA ruled that only six substitutions could be made in such games.

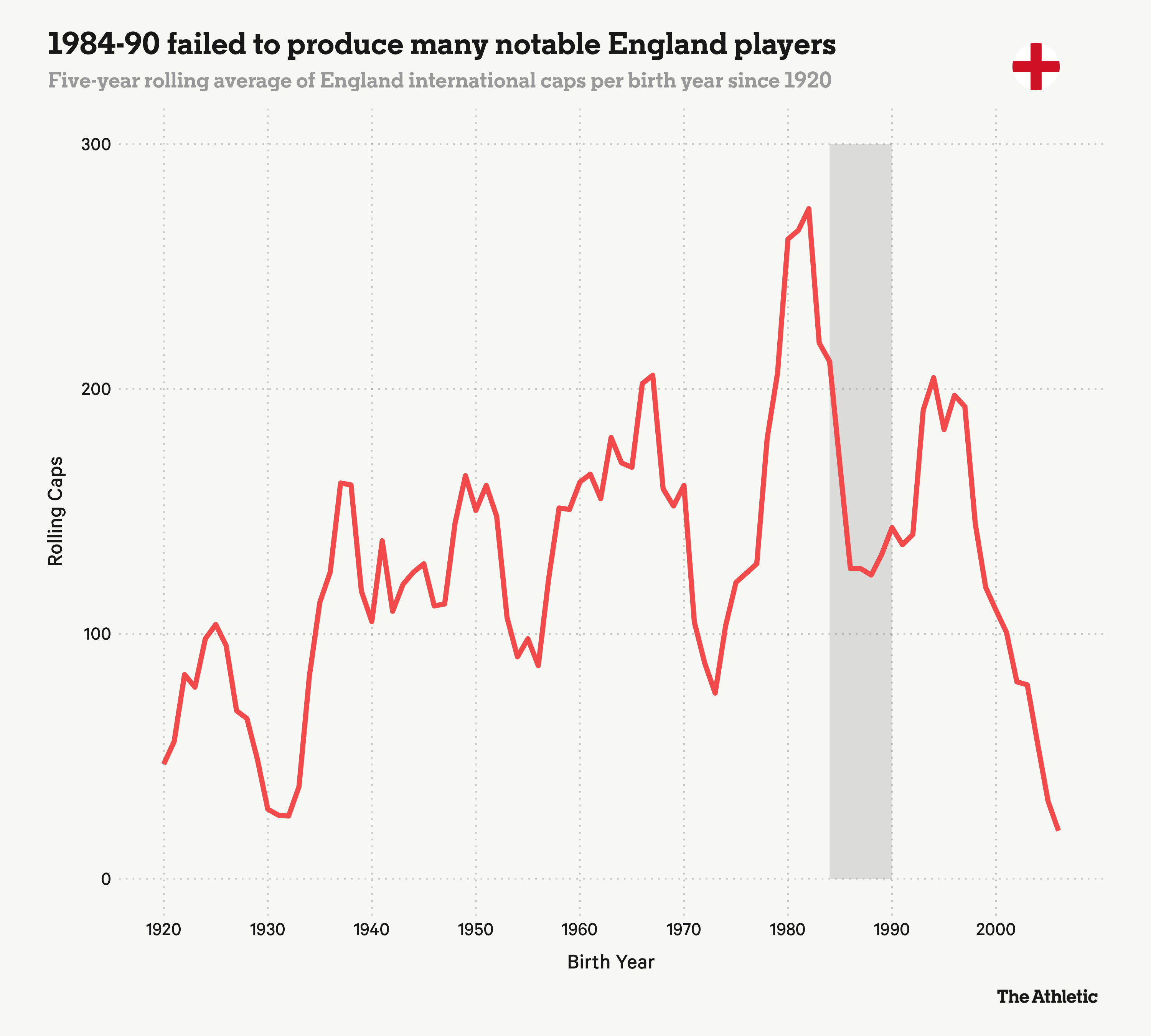

Golden generations are, almost by nature, generally followed by a less impressive one. For England, the mid-to-late 1980s was a particularly poor period. Yes, it featured Wayne Rooney (1985) and Joe Hart (1987), who went on to reach 120 and 75 caps respectively. But otherwise, there were a lot of functional, workmanlike players born: Gary Cahill (1985) and James Milner (1986) are the only others who reached the 50-cap mark.

You could argue that some were under-capped due to England desperately clinging onto the tail-end of the golden generation, but this was a peculiar era featuring lots of players who didn’t live up to their initial promise (Theo Walcott, Andy Carroll), or, conversely, who emerged as England internationals rather late (Adam Lallana, first cap at age 25; Jamie Vardy, 28). It probably wasn’t appreciated how much Roy Hodgson was dealt a poor hand during his 2012-16 tenure, although that doesn’t excuse losing to Iceland in the first knockout round at the 2016 Euros.

But then, like how that summer’s World Cup prompted an upturn in football interest across England, 1990 also produced a wave of players who would contribute to the English national team reaching the past two European Championship finals. The 1990-born trio of Jordan Henderson, Kyle Walker and Kieran Trippier might not be the most glamorous players, but all have had very good international careers.

1993 was a good year for England footballers called Harry (Patrick Hertzog/AFP via Getty Images)

After that, 1993 brought us the two Harrys, Kane and Maguire, and 1994 provided John Stones, Raheem Sterling and Jordan Pickford. These guys were a couple of penalties away from winning the European Championship four years ago.

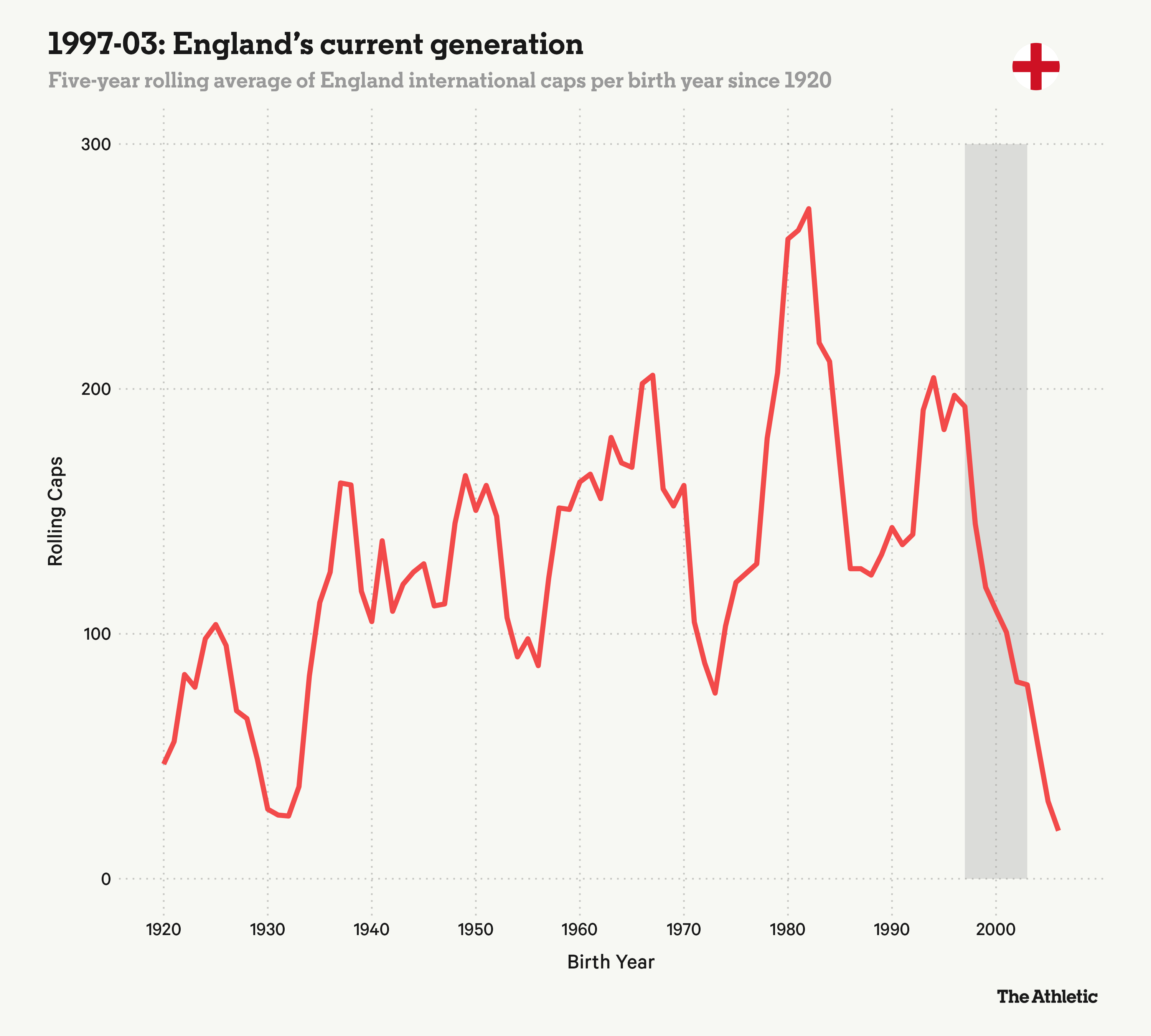

There’s a dip after that — but this, of course, is a bit unfair as the players of this generation are continuing to pick up caps.

The most notable feature of the current crop of players is that there’s been a drip-drip effect, with England producing one outstanding talent each year. Marcus Rashford was born in 1997, Trent Alexander-Arnold in 1998, Declan Rice in 1999, Phil Foden in 2000, Bukayo Saka in 2001, Cole Palmer in 2002 and Jude Bellingham in 2003. While they haven’t debuted in that order — Bellingham got his first senior cap three years before Palmer did, for example — maybe this steady stream of talents is more conducive to success than a sudden glut of top players.

For England, anyway, it feels like a novelty. After a century of a very ‘spiky’ graph, perhaps the years around the turn of this century will represent something more reliable. The key thing, of course, is avoiding another 1976.

(Top photos: Sean Dempsey – PA Images/PA Images; Daily Express/Hulton Archive; Nigel French/Sportsphoto/Allstar via Getty Images; design: Eamonn Dalton)