LIFE, especially the microbes too small to see, has left an indelible mark on rocks on Earth, creating minerals that would otherwise not be there.

If some of those minerals turn up in rocks on Mars, is that not good evidence that life once existed there, too?

Maybe.

Nasa’s Perseverance robotic rover has discovered such minerals in one particular rock on Mars. It came across the specimen in an outcrop of hardened mud along what was once a flowing river.

“I think it’s very intriguing,” Joel Hurowitz, a professor of geosciences at Stony Brook University on Long Island and a member of the Perseverance science team, said in an interview.

He said he had worked on Mars missions for more than two decades and this was the most confident he had been of potential biosignatures in a Martian rock.

“These observations, to me, are really compelling,” he said.

Hurowitz and his colleagues described their findings in a paper published in the journal Nature.

During a news conference, Sean Duffy, the acting administrator of Nasa who is also the secretary of transportation, said: “This very well could be the clearest sign of life that we’ve ever found on Mars.”

Nicola Fox, Nasa’s associate administrator for the science directorate, added context that this was not a definitive conclusion.

“This certainly is not the final answer,” she said.

The news conference highlighted a divide in the stated priorities for Nasa during the Trump administration.

Duffy in his remarks quickly pivoted from the agency’s robotic science missions – a part of Nasa where the White House is looking to make deep budget cuts – to the agency’s human spaceflight programme, including sending astronauts to the moon and eventually Mars.

But he said that science was still important.

“Science isn’t going away at Nasa,” he said. “We are leaning into the science because we need it to make sure that we’re successful on our missions to the moon and to Mars.”

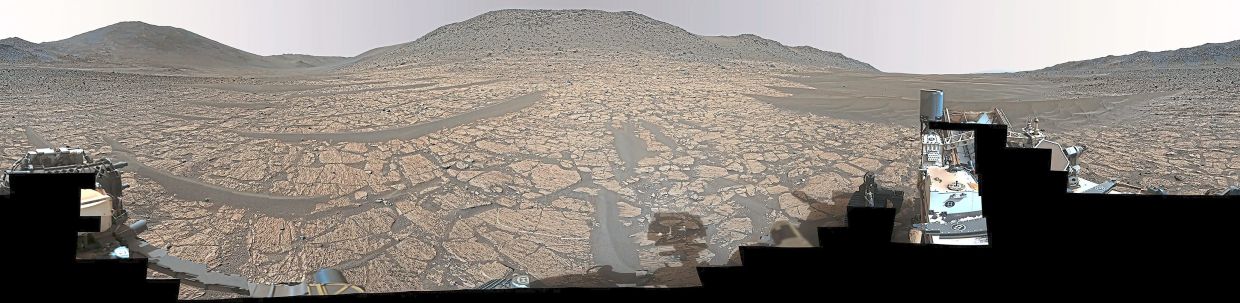

A year ago, Nasa scientists were already giddy about this rock, because it possessed features that were reminiscent of what microbes could have left behind when this area was warm and wet several billion years ago, part of an ancient river delta.

Jezero Crater, the landing site for Perseverance, was once a lake, and the sediments along the river that flowed into the crater were a promising place to look for signs of past life on Mars.

However, Perseverance found few indications of it until this part of the riverbed, one of the rover’s last stops before it exited the crater.

The Nature paper describes in much greater detail the mineralogy of the rock, which the scientists named Cheyava Falls, and of the nearby terrain.

“Last summer was kind of a, ‘Hey, we think we found something really interesting and cool’,” Hurowitz said.

“Now we’re at the point where we’re actually saying in detail, ‘Here is what we have found’.”

What attracted the most attention were what the scientists called poppy seeds – dark specks a few thousandths of an inch wide within the mudstone.

The specks contain vivianite, an iron phosphate mineral.

The scientists also observed larger features nicknamed leopard spots – dark rings containing vivianite surrounding off-white centres that included greigite, an iron sulfide mineral.

“The leopard spots kind of look like they maybe started out as poppy seeds but were able to continue growing to a larger size,” Hurowitz said.

On Earth, vivianite and greigite often form in sedimentary deposits in freshwater lakes, river estuaries and marshlands.

“These would be examples of microbially influenced environments where the microbes are consuming the organic matter and making these minerals as a byproduct,” Hurowitz said.

The minerals can also be produced by chemical reactions not involving living organisms.

But in laboratory experiments, the greigite reactions require heating to more than 250°F, and, so far, it appears that the minerals on Mars formed at cooler temperatures.

“Within the sort of limitations of our rover payload capabilities, they don’t look like they’ve been cooked,” Hurowitz said.

The rock also contains organic compounds – molecules with carbon and hydrogen – which adds more intrigue.

Organic compounds are the building blocks for life, but those, too, can be produced by geological processes that have nothing to do with life.

However, the rocks and the answers they hold may remain stranded on Mars indefinitely.

Last year, the Mars Sample Return mission, which is to bring back the samples that Perseverance collected, was put on hold as cost estimates spiralled upward to US$11bil. Nasa then solicited proposals for alternative possibilities.

In its budget request this year, the Trump administration sought to cancel the Mars Sample Return mission entirely.

“We believe there’s a better way to do this, a faster way to get these samples back,” Duffy said during the news conference.

“And so that is the analysis we’ve gone through. Can we do it faster? Can we do it cheaper? And we think we can.”

He did not provide any details about how or when.

With Nasa’s plans uncertain, the first rocks brought back from Mars could instead arrive on the other side of the planet. China is planning a robotic mission launching in 2028 to collect Martian rocks and drop them off on Earth three years later. — ©2025 The New York Times Company

This article originally appeared in The New York Times.