The Fifth Republic, created by Charles de Gaulle and Michel Debré, operates as a hybrid constitution that has a directly elected five-year presidency and a parliamentary system. It gives a president the right to dissolve the national assembly, hold new parliamentary elections, change prime ministers and reshuffle the government.

Editorial: Fifth Republic

5 September 1958

It is eighty-eight years since Jules Favre demanded the proclamation of the Republic at the Hôtel de Ville in Paris, and fourteen since General de Gaulle refused a repeat performance on the grounds that the Republic had never ceased to exist, in spite of its abolition by Vichy. Now, after the Algerian insurrection of 13 May and the General’s return to power, the moment is approaching when Frenchmen are to be asked to approve a radical overhaul of their institutions – and for those who cherish the republican idea the referendum of 28 September will present a painful choice. The constitution which they are to be asked to approve is one which runs counter to many of traditions dearest to French democrats. The powers of the president are to be strengthened to a degree which earlier generations of French parliamentarians would never have admitted. In particular Article 14, which gives extended powers to the president in case of a national emergency could be used to establish a dictatorship.

The authority of the Chamber is correspondingly diminished, and its laws submitted to the approval of a constitutional court. The constitution, in fact, is intended to limit the effects of universal suffrage and, as such, represents a regression to a transitional type of regime, adapted to the needs of a period when democracy was not yet born and monarchy not yet dead. In these circumstances, it is understandable that many Frenchmen of the left and centre will vote for it only with the utmost reluctance – in spite of the emphasis, in last night’s speech by General de Gaulle, on the legality with which it had been drawn up, and the necessity for a strong executive if France was to take her place in the modern world.

Yet on 28 September Frenchmen will not only be voting for or against a constitution. They will also be deciding whether or not General de Gaulle shall continue in power, and, in the case of the overseas territories, whether or not the link between them and metropolitan France is to be maintained. A rejection of the constitution and the General would once again bring France to the brink of civil war. A “no” from French Africa would mean the end of the most imaginative effort yet made by France to lead her colonies towards self-government. For both these reasons French democrats would be pursuing a politique du pire – or choice of the worst – were they to return a negative answer to the referendum.

The referendum and after: De Gaulle’s un-republican allies

By Darsie Gillie

11 September 1958

On 28 September, in the referendum on his new constitution, General de Gaulle will sweep into a single net the votes of Africans welcoming the right to secede and of conservative Frenchmen who want a strong government to discourage if not prevent any such secession; of General Chassin, leader of the “May 13 movement,” who says that his “yes” is for a French Algeria and integration but not for the constitution, and that of M. Gaston Defferres, the Socialist mayor of Marseille, who wants a stable government to negotiate with the Algerian rebels. Leaders of the centre and left talk of a new government that will at last be able to carry out their parties’ policies; leaders of the Right rub their hands in joy at the hope of an electoral law which will at last give them a majority in the assembly, even if they do not possess it in the country.

This masterly political manoeuvre is only possible because of the General’s personal prestige and of the widespread disgust with the feeble flappings of the Fourth Republic. That the General is a disinterested patriot with a unique position in his country’s recent past, with a very distinguished mind and a wider view of public interests than most of his fellow-citizens is true. That the Fourth Republic broke down after repeated failures to repair its mechanism and mend its ways is also true. The general’s criticisms of the constitution of 1946 were from the first shrewd, and naturally give authority to his positive recommendations now about to enter into force which were not necessarily equally valid.

Continue reading here and here.

Revulsion against Fourth Republic

From our own correspondent

30 September 1958

General de Gaulle is himself among the most surprised at the tidal wave of votes supporting him. It has:

1. Approved his constitution

2. Given him all the moral authority he could desire to wield the extraordinary powers granted him by the constitution for the four months during which the new institutions are to be set up, and

3. Freed him from the danger of becoming the prisoner of any one group of his supporters.

skip past newsletter promotion

Sign up to This is Europe

The most pressing stories and debates for Europeans – from identity to economics to the environment

Privacy Notice: Newsletters may contain information about charities, online ads, and content funded by outside parties. If you do not have an account, we will create a guest account for you on theguardian.com to send you this newsletter. You can complete full registration at any time. For more information about how we use your data see our Privacy Policy. We use Google reCaptcha to protect our website and the Google Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.

after newsletter promotion

The General, who arrived back in Paris this morning, to prepare for a cabinet meeting tomorrow, does not appear to have expected more than 70 per cent, and would have been pleased with that. The new constitution will be promulgated next Sunday, after verification of the vote.

Birth of Fifth Republic

6 October 1958

On the first day of the Fifth French Republic General de Gaulle told a cheering crowd of 100,000 in Lyons today: “The new constitution launches France in a new era of greatness – and I can guarantee it.” Little by little, he said, France was “reassuming the place she merits … her place in the first rank of the world powers”.

His triumphal visit to Lyons came at the end of a four-day tour that had taken him to towns in Algeria, Corsica and France. The only unenthusiastic report came from Algeria where the Europeans were apparently uneasy about his promise to bring the 9,000,000 Muslims up to the French living standard within five years and to give them equal political rights.

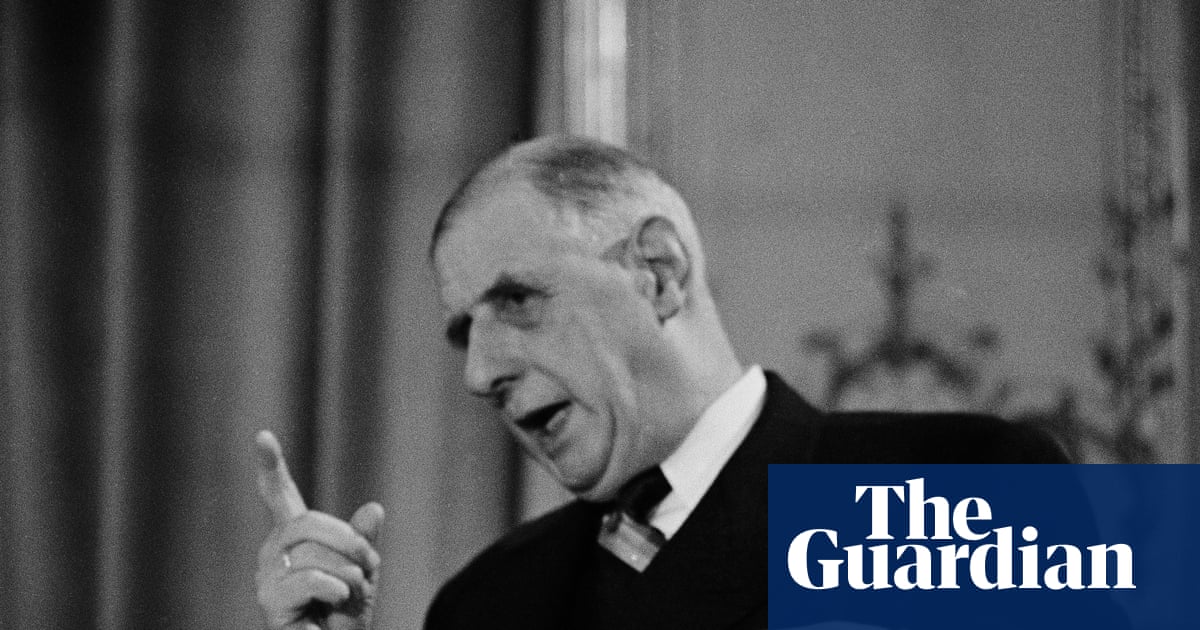

French president General de Gaulle addresses a crowd of 100,000 at the Place de Republic in Paris on 4 September 1958. Photograph: AP

The constitution officially came into effect, today, when the complete text was published in the Official Journal. The new Republic will be officially inaugurated in Parts tomorrow evening, when members of the government sign a copy of the constitution.

“Any measures needed”

In the next four months, according to the constitution, electoral procedures must be fixed and a new parliament and president elected. Then the president must nominate a prime minister and decree the government into office. In the meanwhile General de Gaulle’s government can take “any measures needed in the interests of the nation.”

The final results of the referendum on the constitution were published today. Of 36,486,251 valid votes cast. 31,066,502 said “Yes” and 5,419,749 said “No.” These results did not include the former French guinea, which voted against and gained independence by 1,136,324 “no” votes to 56,981 “yes” votes.

The French Communist party’s central committee has ended a two-day inquiry into the reason why 1,000,000 of the 1,500,000 regular Communist voters ignored the party campaign against General de Gaulle. It laid the blame on the division of left-wing forces which refused an alliance with the Communists, but it added that the party must improve its contact with the masses.