By Michaela Cabrera

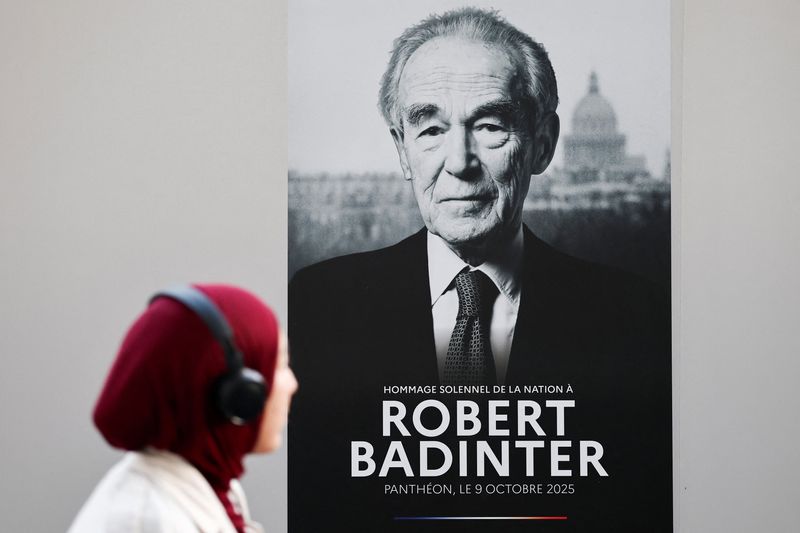

PARIS (Reuters) -President Emmanuel Macron will on Thursday inaugurate a cenotaph in memory of Robert Badinter at the Pantheon, a mausoleum in central Paris where some of France’s most prominent national heroes are buried.

The former justice minister, who died in February 2024 aged 95, will join the likes of philosopher Voltaire, writer Victor Hugo and scientists Pierre and Marie Curie in the monument’s vast, vaulted crypt, which has been used to host the remains of great figures since 1791.

The cenotaph will contain Badinter’s legal gown, three books that he cherished, and a copy of his most famous speech, the Élysée Palace told Reuters on Wednesday. His body will remain in the Jewish section of Bagneux cemetery, just south of Paris.

“The time has come for the nation to show its gratitude,” Macron said during a ceremony last year in which he announced Badinter’s future commendation. “Your name will be inscribed alongside those who have done so much for human progress and for France and who await you at the Pantheon.”

Badinter, who declined all national honours in life, will now, in death, receive France’s highest one. Who was he?

ABOLISHING THE GUILLOTINE

Badinter is best known, and most widely celebrated, for having led France’s abolition of capital punishment.

“Tomorrow, thanks to you, French justice will no longer be a justice that kills,” the lawyer turned justice minister told the National Assembly, which voted for abolition, in 1981. “Tomorrow, thanks to you, there will no longer be, to our common shame, stealthy executions, at dawn, under the black canopy, in French prisons.”

His impassioned speech is ingrained in national memory, as are his slender silhouette and bushy eyebrows.

While acknowledging victims’ desire to see the guilty die, he added: “All historical progress in the field of justice has been about moving beyond private vengeance. And how can we move beyond it, if not by first rejecting the law of retaliation?”

The guillotine, France’s instrument of decapitation since the fall of the monarchy in 1792, was finally retired on Oct. 9, 1981. Badinter’s cenotaph will be unveiled on the anniversary of that law.

‘FROM INTELLECTUAL CONVICTION TO MILITANT PASSION’

Badinter would come to be hailed as the nation’s moral conscience. But his single-minded drive to quash a centuries-old practice made him highly unpopular in 1970s France.

Anger towards him peaked when he defended Patrick Henry, who stood accused of killing a seven-year-old boy. Badinter was labelled “the assasins’ lawyer”, his wife and children received death threats, and a small bomb exploded on their doorstep.

Following a highly-charged trial, in 1977, during which crowds shouted “Death, death!”, Henry was found guilty but spared the guillotine.

Badinter lost cases, too. In 1972, he was powerless to stop the beheading of his client Roger Bontems, who was convicted of having helped take a guard and a nurse hostage in prison, but acquitted of their murder.

After the trial, he crossed the threshold “from intellectual conviction to militant passion”, he wrote in his 2000 book “The Abolition”. He vowed to fight “with all his strength” for the death penalty to be abolished.

After his election to the presidency in 1981, François Mitterand put Badinter in charge of the ministry of justice, to fulfill a campaign promise of getting rid of the guillotine.

“A simple idea governed Robert Badinter’s life: in order not to lose faith in Man, one must not kill men, even if they are the worst culprits,” Macron said last year, following his death.

‘RACISM IS PURE INHUMANITY’

But abolition was not the only issue dear to Badinter.

Three months after scrapping the death sentence, lawmakers voted to pass another measure he’d authored, this time for the equal treatment of sexual orientations. Previously, consent for homosexual acts could only be given from the age of 21, whereas it could be given for heterosexual ones at 15. At Badinter’s initiative, France’s parliament levelled the age of consent.

He also fought racial discrimination, which he had himself experienced.

The France that Badinter’s Jewish grandparents emigrated to in 1921, fleeing the pogroms of Tsarist Russia, was perceived as a country where Jews could live as citizens with rights and dignity, he wrote in a biography of his grandmother, “Idiss”. The book is one of those that will be placed in his cenotaph, the Élysée said.

Badinter was 12 when the Nazis occupied Paris. He witnessed curfews, segregation in public transport, and a playground ban on Jewish children. Fleeing persecution once again, his family hid in the French Alps.

“Racism, all forms of racism, is pure inhumanity,” he said on the French talk show “Quotidien” in 2018. “And I’ve experienced it and I know it well.”

Badinter’s father was rounded up in Lyon by Nazi officer Klaus Barbie and sent to the Sobibor extermination camp, in eastern Poland. Decades later, when Badinter was justice minister, Barbie was extradited to France from Bolivia to face trial. Among the evidence in the case file was a photograph of a list of Jews sent to the camps. The name of Badinter’s father, Simon, featured on that list, as did Barbie’s signature.

“His death was to me a secret wound, ever open,” Badinter wrote of his father in the 1973 book “The Execution”.

DECRYING PUTIN’S WAR

Badinter drew the ire of the Jewish community in 2001 when he supported the release from prison of Nazi collaborator Maurice Papon, ill at 91 years old.

“Even if it is a crime against humanity, humanity must prevail over crime,” Badinter wrote in the newspaper Le Monde.

In his 80s, as an emissary for UNICEF, Badinter continued to advocate for prisoners’ rights, visiting youth detention centres in Eastern Europe and denouncing their dismal conditions.

Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine in 2022, the return of total war on European soil, hit home for Badinter. “More than dismay, it was despair,” Bruno Cotte, a longtime colleague, said of the former minister’s feelings at the time.

With Cotte, Badinter penned a book urging the indictment of Russian President Vladimir Putin for war crimes and crimes against humanity.

Badinter is the sixth person to be inducted into the Pantheon during Macron’s presidency. The others were Simone Veil, who authored the 1975 law decriminalising abortion in France, singer Josephine Baker, the first Black woman in the mausoleum, the author and World War I veteran Maurice Genevoix, and World War II resistance fighters Missak and Mélinée Manouchian.

(Editing by Olivier Holmey)