PARIS — As Israel marks the second anniversary of the deadliest day in its history, the commemoration will also hit close to home for many in France, whose citizens, after Israelis, suffered the greatest losses in the October 7, 2023, massacre.

Of some 1,200 people slaughtered in the carnage, 48 were French nationals. Many more were among the 251 kidnapped and thousands wounded.

For Paris journalist Rachel Binhas, whose book about October 7 is devoted to the French victims and her country’s response to the epochal disaster, the anniversary will be no ordinary day.

“October 7 was not just an Israeli event,” Binhas told The Times of Israel during an interview at a Paris café on Rue Mouffetard, one of the city’s oldest streets. “It was also a French event which, to this day, is felt by many people in France, directly and indirectly.”

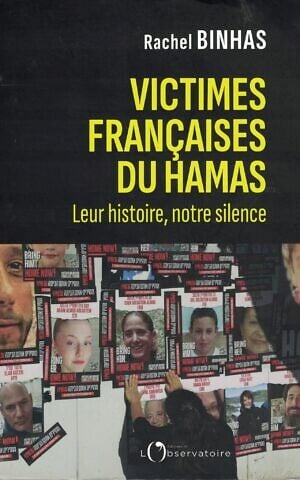

Her French-language book, “Victimes françaises du Hamas: Leur histoire, notre silence” (“French Victims of Hamas: Their Story, Our Silence”), makes for a sobering read. Far more than a simple chronicle, its three sections — “Our Victims, Their Story”; “The Effects of October 7 in France”; and “A France without Jews?” — include detailed portraits of seven French victims, retracing their steps in the hours leading up to the Hamas massacre. Alongside is heart-wrenching testimony from the victims’ families, analysis of French society and questions about surging antisemitism.

Get The Times of Israel’s Daily Edition

by email and never miss our top stories

By signing up, you agree to the terms

Collectively, the victims and their families represent French Jewry, writ large. They include secular, religious, Ashkenazi, Sephardic, progressive and conservative — some still strongly linked to France, others not. Tragically ironic, some had left France due to rising antisemitism, thinking they would be safer in Israel.

“My book is a way of paying homage to the French victims,” Binhas says. “It’s also to preserve their memory and help ensure their story isn’t forgotten while exploring how so much of French society responded with deafening silence and what it means for French Jews.”

Given how many of those killed on October 7 had French citizenship, Binhas points out that it represents the fourth most murderous terrorist attack involving French nationals. As such, she expected the massacre’s French victims to figure more prominently in French consciousness.

“I quickly realized, and I wasn’t the only one to notice, that the French victims of October 7, victims in the broadest sense of the word, meaning not only those killed but also those kidnapped and wounded, were surprisingly receiving little attention in French media, in the cultural sphere and French society in general,” says Binhas. “Concerning the hostages, it was in sharp contrast to how the country mobilized in previous cases of French citizens kidnapped abroad.”

Eight French citizens were among those kidnapped during Hamas’s terrorist onslaught. Eventually, five were released alive, concluding with Ofer Kalderon’s freedom last February after 484 days in Gaza. The bodies of the three killed in captivity were returned to Israel, the last of whom was Ohad Yahalomi, last February.

Demonstrators gather to call for the freeing of the hostages held in Gaza since the Hamas-led October 7, 2023, terrorist onslaught on Israel, at the Trocadéro esplanade with the Eiffel Tower in the background in Paris, on April 7, 2024. (Photo by Thomas SAMSON / AFP)

Binhas cites how France responded to the plight of Jean-Paul Kauffmann in Lebanon in 1985, Ingrid Betancourt in Colombia in 2002 and Didier Francois in Syria in 2013, for whom there were numerous solidarity actions, including daily reminders on nightly newscasts, and their portraits displayed on municipal buildings around the country.

“While in captivity, these former hostages had a real presence in the public space, in the media and in the consciousness of French people,” adds Binhas. “I saw the difference when I’d ask people around me, if they knew, if not the names, at least the number of French hostages that Hamas was holding in Gaza. Most had no idea there were even French hostages. It was this invisibility, this lack of awareness and sometimes just indifference that helped drive me to write the book.”

People walk past a billboard bearing a message addressed to French President Emanuel Macron in Tel Aviv on November 21, 2023, demanding the release of Israelis held hostage in Gaza since the October 7 attack by Hamas terrorists. (Photo by AHMAD GHARABLI / AFP)

Published last fall, it began as an article Binhas composed for the weekly magazine Marianne, where she’s a staff writer. A French publisher, Éditions de l’Observatoire, then asked her if she would do a book on the subject as part of its interest in Jewish-related issues in France. This year, it also published “Francaise, juive et alors” (“French, Jewish, and So What?”) by Shannon Seban, which focuses on contemporary antisemitism in France.

Jews are people, too?

Binhas remains deeply troubled by how many of her compatriots reacted to the brutal mass murder of Israelis.

“In the weeks following October 7, I noticed that in France most people seemed to have trouble showing some degree of compassion for Israel, and to suspend even temporarily their political views about the Middle East,” she adds. “It was as if the Jewish victims of October 7 and their loved ones weren’t entitled to empathy or sympathy. It seemed Israelis and Jews didn’t merit the status of genuine victims because they were Jewish.”

In many cases, hate was evident.

“What we saw instead in France was an explosion of antisemitic acts,” she adds. “This disappointing response said something about France. What was the reaction of those in politics, culture, media and sports? I wanted to analyze that in the book along with telling the stories of the French victims themselves.”

Footage shows the Paris offices of El Al vandalized with red paint and pro-Palestinian, anti-Israel graffiti, August 7, 2025. (Theo Wargnier/Jeremy Martin/AFPTV/AFP)

For all her criticism of how many in France responded, Binhas acknowledges actions by the national government that contrasted with most other areas of French life.

“The French government has done everything that was in its power to come to the aid of the French families of the October 7 victims,” she writes early in the book. “From the Foreign Ministry to the Elysée Palace, the mobilization was total, taking sometimes unexpected forms, such as doing right after the fact to arrange French citizenship for certain victims who had delayed the process.”

French President Emmanuel Macron and his wife Brigitte Macron arrive to host a ceremony to pay tribute to the French victims of the October 7, 2023, Hamas atrocities, at the Invalides memorial complex in Paris, on February 7, 2024. (Photo by GONZALO FUENTES / POOL / AFP)

She also cites the highly moving memorial event that French President Emmanuel Macron presided over in Paris on February 7, 2024. At the outdoor ceremonial tribute, where Republican guards held large photos of all the French victims, including the then-hostages, Macron called October 7 the “biggest antisemitic massacre of our century” and “barbarism… fed by antisemitism.” Many of the family members were flown to the ceremony at the government’s expense.

Under Macron’s leadership, France has supported efforts to release the hostages. He himself has met multiple times with hostage families, as recently as this month in Paris.

‘I could taste the poison of antisemitism’

As part of her research, Binhas went to Israel several times to interview families whose loved ones were killed, kidnapped or wounded during the Hamas atrocities. What victims’ relatives told her, amid their pain, forms the first half of the book, by far its most poignant part.

“One of the challenges was getting families to speak to me without me being insistent,” says Binhas. “I wanted to be sensitive to their situation. People were in a particular moment in their mourning. Some felt the need to speak, others didn’t.”

Other challenges arose later.

“I was working on the book amid a sharp rise in antisemitism in France,” says Binhas. “I felt it especially when the book came out and I was promoting it. There were some very hard reactions. I could taste the poison of antisemitism.”

‘French Victims of Hamas,’ by Rachel Binhas. (Courtesy)

Some of it came from colleagues.

“I received comments from certain journalists that — and I say this diplomatically — were awkward,” she adds. “Some media outlets deliberately ignored the subject of the book because it didn’t correspond to their perspective. Certain bookstores were no better, either refusing to stock it or relegating it to the back of their stores.”

The bias and intimidation weren’t relegated to live interactions, Binhas says.

“A person who ordered the book online told me it arrived with comments scrawled in it, such as ‘Free Palestine,’ on the page where I list the names of the French killed on October 7,” she says. “All this without mentioning all the invectives, insults and threats of violence I received on social media — and it still continues to this day.”

Despite this, Binhas remains undaunted.

“It’s not so much fear I feel as anger,” she says. “It pushes me. Of course, you never know what can happen. People say there’s always a risk that a crazy or unbalanced person will find the current [antisemitic] climate auspicious to do something dangerous.”

What Binhas has observed in France since October 7 makes her more concerned for her Jewish compatriots.

“The current reality doesn’t lend itself to optimism,” says Binhas. “You need to be lucid. I sometimes see myself as an informed optimist, but I agree with pessimists on several things not evolving in a good direction, especially relating to Jews. We see something disturbing settling in and taking hold.”

Protestors chant and wave flags as they demonstrate in support of convicted Lebanese terrorist Georges Abdallah ahead of the Paris Court of Appeal’s decision on his release, in Toulouse, southwestern France, on July 14, 2025. (Valentine CHAPUIS / AFP)

For Binhas, that there’s no state antisemitism provides some solace amid concerns it’s becoming normalized elsewhere in French society.

“Since October 7, we’ve seen an antisemitism we had thought forgotten and relegated to the margins of society woken up again,” she adds. “It’s gaining momentum with a rhetoric often validated politically by Jean-Luc Mélonchon’s [left-wing] France Unbound party. Its origins may be deeply rooted, but its current form is new.”

The impact is troubling.

“This antisemitism has instilled a certain fear in many French Jews, among whom you see an ‘invisibilization’ of practices in the name of safety and security,” she adds.

“I’ve seen this hiding of one’s Jewish identity among people I know. Changing one’s name on Uber and delivery platforms so it won’t look Jewish, removing the mezuzah on one’s door,” she says. “Few Jews would say this is paranoia, especially as we know sometimes antisemitism goes from the verbal to physical acts, and that’s a strong reality in France now.”