For nearly 25 years, scientists were stumped. Feathers had been found in the droppings of Europe’s largest bat, the greater noctule.

Carlos Ibáñez, a Spanish biologist, was convinced that the species, found across Europe and North Africa, was catching songbirds on the wing. But filming the bats while they hunted at night was impossible and attempts to track them using radar failed.

Sceptics scoffed. A bat had never been seen consuming a bird. The greater noctule must occasionally swallow lone feathers, they said, mistaking them for insects. How, they asked, could a mammal scarcely heavier than a golf ball bring down a robin mid-flight?

• Bats ‘surf’ wind to travel hundreds of miles in a night

Now the case has been cracked. An international team of researchers has caught the bats in the act by fitting them with tiny backpacks containing microphones and motion sensors.

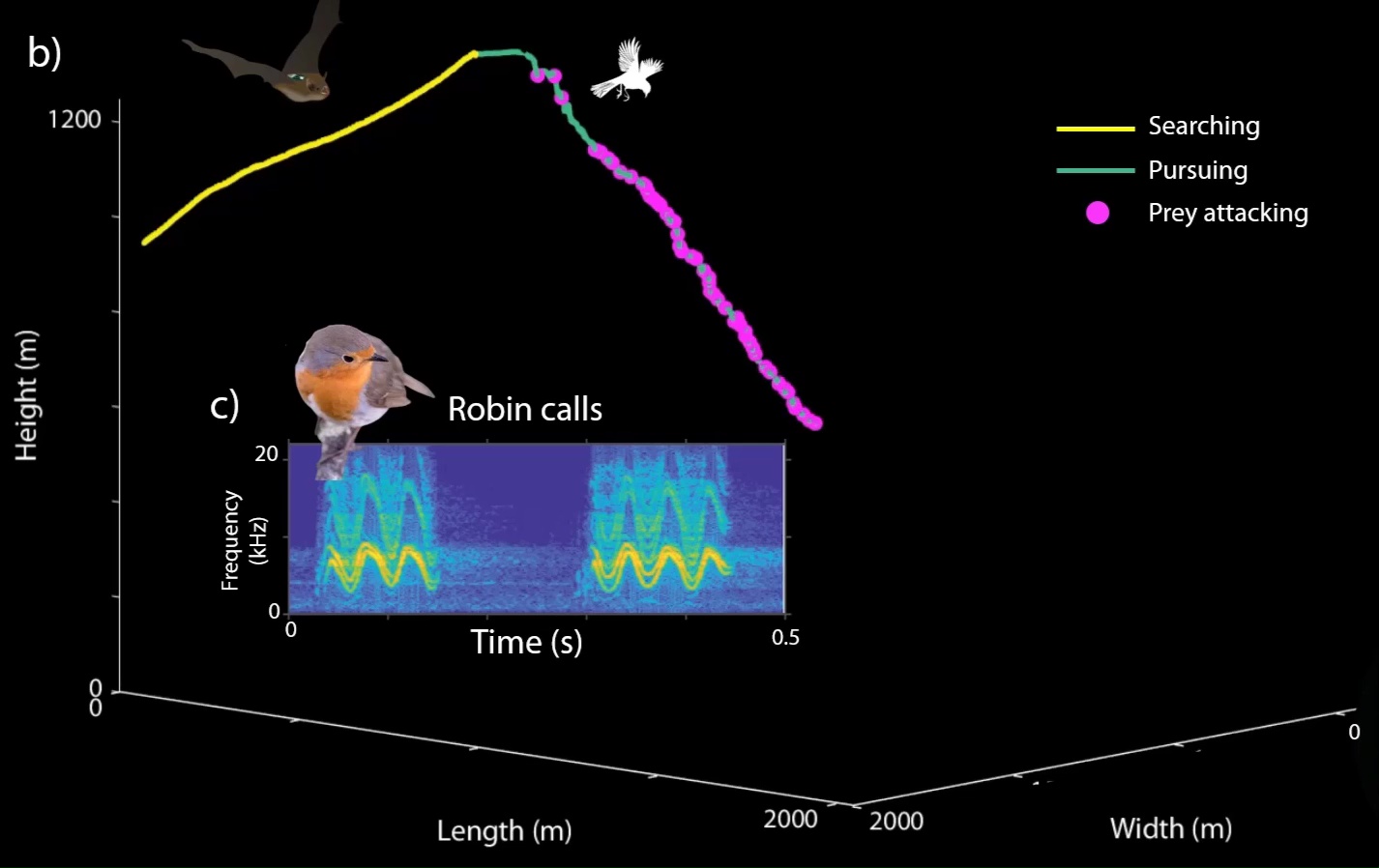

The results, published in the journal Science, reveal how noctules pursue their prey in steep, breakneck-speed dives towards the ground, much like fighter aircraft in dogfights.

One audio recording captures the distress calls of a terrified robin as a bat repeatedly comes close to snatching it out of the air. It culminates with the sound of a successful predator munching on its quarry.

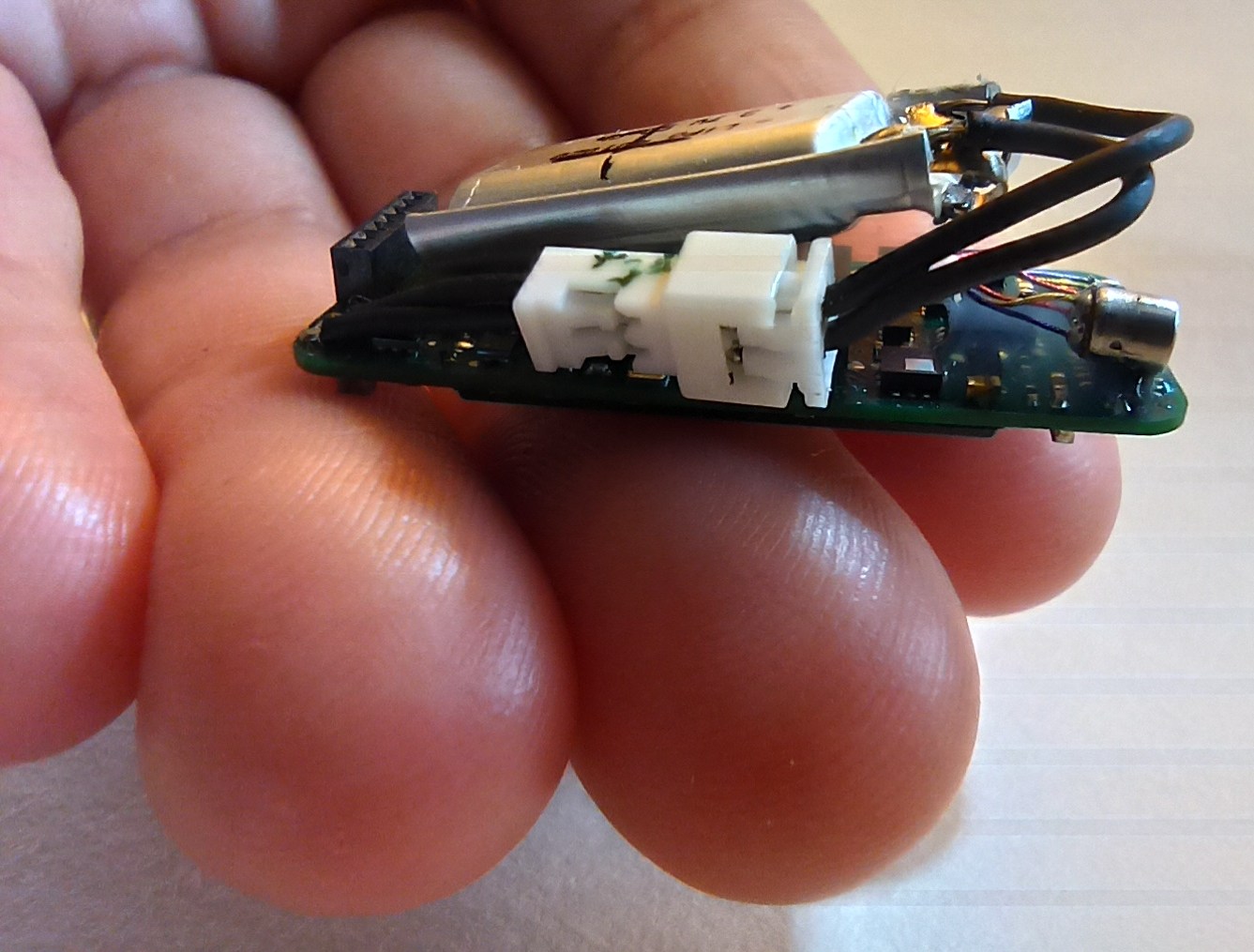

The miniature backpacks were developed by Mark Johnson and Peter Teglberg Madsen at Aarhus University in Denmark. Weighing about 3g, they included instruments that recorded altitude, acceleration and sound. The team placed the backpacks in party balloons to protect them, and used medical glue to stick them to bats, which weigh 40-60g. The bats, which were using roosting boxes that were regularly monitored, had already been fitted with tiny microchips to monitor their comings and goings.

The advent of ultralight sensors that researchers could put into a bat-sized backpack allowed them to confirm a 25-year-old hypothesis

ELENA TENA

The data showed the noctules soaring more than a kilometre above ground, then diving in pursuit of migrating songbirds. The bats descend at an average rate of 8m a second, but will accelerate in bursts to much faster speeds.

As in an aerial duel, the bat locks on and attacks, signalled by a rapid burst of echolocation pips. The birds, unable to hear the bat’s ultrasound calls, remain oblivious until the last moment.

One chase recorded by the researchers ended in stalemate after a 30-second dive. Another finished less happily for a robin: after nearly three minutes of pursuit and 21 distress calls, the recording captured 23 minutes of steady chewing. By contrast, when the bats capture insects, they chew for ten seconds or less.

Over 20 years Ibáñez had collected several severed songbird wings which were found on the ground, and stored them in a freezer. Laura Stidsholt of Aarhus University, lead author of the study, said she and her colleagues believed that the bats chewed off the birds’ wings to reduce drag.

Researchers used their data to visualise a bat attack on a robin. After a vertically downwards sprint of several minutes, the bat catches its prey

LAURA STIDSHOLT

The detection of bat DNA on the gnawed-off wings supported this, said Elena Tena of the Spanish National Research Council, a co-author.

The researchers suspect that the robin, which would have weighed 16-22g, was folded into a membrane between the bat’s legs, allowing it to consume its prey mid-air.

The discovery is the result of decades of persistence. Ibáñez, who is based at Spain’s Doñana Biological Station, first found feathers in greater noctule droppings in the 1990s. Over the years, his team tried several monitoring techniques: cameras, radar, microphones on balloons. Nothing had caught the bats in action.

Only with the advent of the ultralight backpacks did the crucial evidence emerge, vindicating Ibáñez’s hypothesis as he nears retirement.

The bats pose little danger to songbird populations. The greater noctule is rare and, in many regions, endangered because its forest habitats are disappearing. The findings could help conserve them: understanding their feeding and flight patterns may aid efforts to protect its hunting grounds.