When he was a boy James McGuinness was OK being British. Not any more.

The 23-year-old musician and independence supporter now considers himself Scottish.

“I was a bit naive as a teenager and I didn’t know too much about history or about modern politics, I’d probably have whacked ‘British’ on a form as well as — or instead of — ‘Scottish’,” he said, stopping for a chat in Glasgow’s Buchanan Street. “But now if ‘British’ is the only option, I’m not happy.”

Fellow musician Jamie McTear, also 23, agreed. “I just feel that British isn’t really a culture, whereas Scottish is,” he chimed in. “I’m proud to be Scottish, I’m not really proud to be part of a union.”

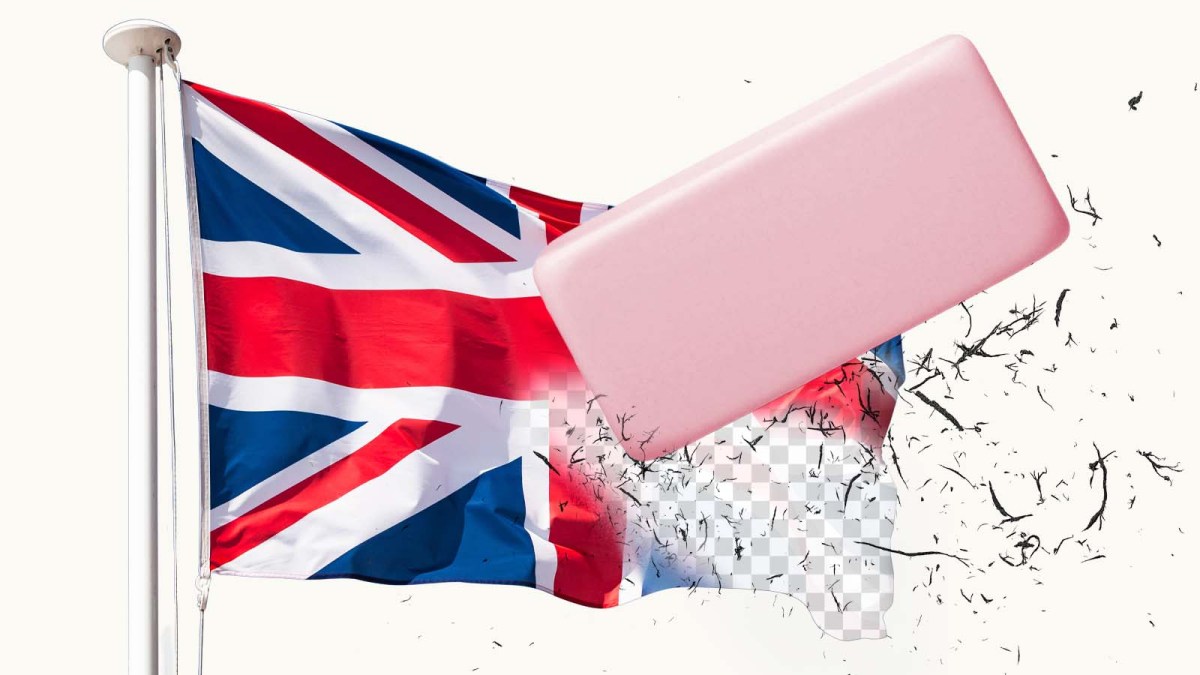

The men, both from Scotland’s biggest city, with its Yes majority, are not alone. British identity is in retreat north of the border.

New figures from the Scottish Social Attitudes (SSA) survey, a gold-standard long-term academic study, last week showed just how quickly this change is taking place.

As recently as 2017, the year after the Brexit referendum, 54 per cent of respondents said “British” was at least one way they could be described. By last year, according to the latest data, the number had dropped to just 25 per cent.

On the same relatively crude measure, Scottish identity is also in decline, albeit far less dramatically.

What is happening? More people see themselves as singularly Scottish or British, rather than both. This tends to tally strongly with their political outlooks, and not just on the constitution.

Political scientists say Scotland is increasingly — but not yet completely — split into two tribes.

The first feels Scottish, leans left and supports independence. The second identifies as British, tilts to the right and backs the United Kingdom.

There is still support for Scottish independence and groups such as All Under One Banner are still organising marches for the cause

JANE BARLOW/PA

Mark McGeoghegan, a political researcher at the University of Glasgow, said: “Scottish identity is increasingly decoupling from British identity.

“It’s not that the share of people in Scotland who identify as Scottish has grown — it has shrunk from 84 to 74 per cent between 1999 and today. Rather, the part of the population which identifies as British has collapsed.”

The increasing number of Scots identifying as only as Scottish is associated with greater support for independence, McGeoghegan explained.

“We are yet to tease apart what is driving this shift, but we know it is partly down to generational change as younger Scots are more likely to support independence and identify only as Scottish,” he said.

“Yet there must be something else going on, as the collapse in British identity is too sharp to only be produced by generational change.”

McGeoghegan had previously used the SSA data to test whether pro-independence Scots became more unionist as they grow older. He found they did not.

“The reality is that the underpinnings of Scottish unionism, and the interlinking of Scottish and British identity, have been consistently eroded since the end of World War Two and the death of the Empire,” he said.

“Where the Empire, and the Union, once offered enormous economic benefits to Scots, that has become less and less the case for decades.”

He said the 2008 financial crash, the 2014 independence referendum and 2016 Brexit referendum might “merely have been the straw that broke the camel’s back”.

• Eleven years after defeat, Yes shops remain and they’re armed with cake

“Scots increasingly don’t identify with Britain because there is little reason for them to do so,” he claimed.

The SSA survey did not just ask people a simple question about identity. It also offered respondents a more nuanced, gradual scale, going from “Scottish not British” through, “more Scottish than British”, “equally Scottish and British” and “more British than Scottish” to “British, not Scottish.”

The last two categories remained very small, between them representing about 10 per cent of the population. The SSA survey found “Scottish not British” rising to 36 per cent last year, from a steady 24 per cent in 2015-17. It is now the biggest single category as “more Scottish than British” and “equally Scottish and British” dipped.

The official census asked a similar question on national identity with fewer categories. The 2022 survey found 63.5 per cent were Scottish only, 13.9 per cent were British only and only 8.2 per cent were “Scottish and British”. The last option lost 10 points in a decade.

The psephologist Sir John Curtice, a professor at Strathclyde University, last week crunched numbers for 25 years worth of SSA data, from 1999, the first year of devolution, to 2024 in a paper published for the National Centre for Social Research.

Curtice and his colleagues persistently found Scotland to be only a little more left-wing than the rest of the UK and that this gap has not grown over the last quarter of a century. But writing for The Conversation, a website that provides a platform for academics, Curtice stressed there was now an increasing correlation between Scottish-only national identity, left-wing politics and support for independence.

The SSA survey offers a far more detailed look at Scotland’s constitutional mood than a simple Yes/No poll. Instead of a binary choice, the SSA prompts its 1,500 respondents to choose between independence, devolution or the pre-1999 “no parliament” position.

As of last year support stood at 47 per cent for independence, 41 per cent for devolution, and 9 per cent for the pre-1999 situation.

But as Curtice underlined, these top-line figures masked a dramatic shift driven by identity and political ideology — a depth regular polls simply can’t capture.

Curtice highlighted the growing chasm: “Support for independence among those who feel wholly or predominantly British is, at 14 per cent, only eight points higher now than 25 years ago.” In stark contrast, among those who say they are “Scottish, not British”, 74 per cent now support independence — an explosive 30-point increase.

The divide is just as wide on the political spectrum. In 2000, those on the left were 15 points more likely to favour independence; that gap has now exploded to 34 points. Today, 64 per cent of those on the left are in favour, but only 30 per cent of those on the right.

“The constitutional debate has become more polarised,” Curtice concluded. “No longer is it simply about how much sovereignty the country should have. Rather, it has become more strongly embedded in differences of identity and disagreements about the proper direction of public policy.”

Back in Glasgow, McTear, who voted tactically for Labour at the last UK general election, also underlined what he saw as a connection between opposing independence and right-wing thinking. “I feel like Scotland is generally more left wing than England,” he said. “A lot of the conservative people are a lot more unionist.”

Nicola Broadfoot. the managing director of an engineering firm, did not share McTear’s pro-independence stance but is also less happy to be British.

Nicola Broadfoot identifies as both Scottish and British

ANNA DOWELL

“I’m much prouder to be Scottish than I am to be British,” said Broadfoot, 47, who is originally from St Andrews but lives in Newcastle. “I definitely think being a united country, being British, is good but at the minute we’re getting a really bad reputation and the word ‘British’ is getting quite negative connotations.

“I think that Brexit has excited these feelings that we’re seeing right now more.”

The latest SSA survey found trust in the Scottish government to work for Scotland’s best interests had dropped to its lowest level since devolution, to 47 per cent. Confidence in the UK government to do the same was even lower, at 21 per cent.

Have people, scunnered with nationalist leaders at Holyrood, abandoned Scottish identity? In Glasgow, Grant Gibson has not.

“I’m not a fan of the SNP, and I think they have basically ruined the country,” the 52-year-old, originally from Blantyre, said. “But I’m still Scottish, I’ve always been both Scottish and British; I think we are better together.”