Across England, more than 83,000 children are currently in care, the highest number on record Nichola Anne at home in Ainsdale(Image: Liverpool Echo)

Nichola Anne at home in Ainsdale(Image: Liverpool Echo)

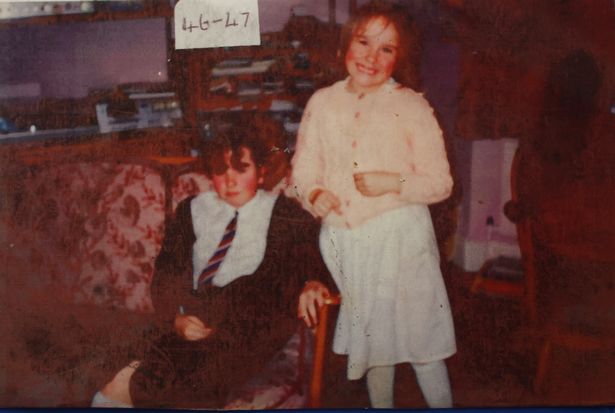

“I was known as number 46”, remembers Nichola Anne as she looks at a childhood photograph. It shows Nichola and her sister in foster care, after being removed from her family home.

After years of silence, Nichola is speaking out about her childhood and growing up in the care system. Her story is of a life marked by violence and abandonment, but also one of hope and survival. Part of the motivation for sharing her story is to try and shine a light on the experiences of people who grow up in care.

Nichola said she has witnessed some negative commentary from people worried about children’s homes in their area.

She said: “I grew up in care and I am a care leaver. Negative posts about children living in care homes are upsetting.

“Children don’t go into care because they’re bad or dangerous. Often, it’s because of circumstances far outside their control.

“We know the support to keep families together isn’t there. Too often, it’s children in care and care leavers who are judged, feared, or treated as if we don’t belong.

“So I’m sharing this for transparency. I am a care leaver, a mum, a grandma, and a co-founder of a support group for parents. Care leavers do struggle but they’re capable of so much, just like everyone else.’

In recent months, the Liverpool ECHO has attended several council meetings in Merseyside, where planning applications for new care homes have been evaluated.

The vast majority of those applications have been met with objections from local residents who have expressed concerns about the surge in private sector involvement in children’s care.

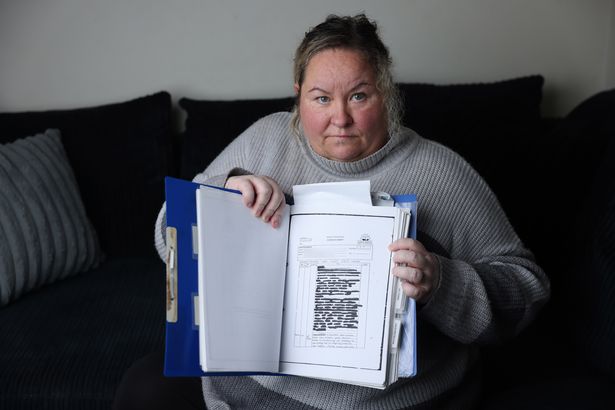

Nichola Anne with records from her time spent in care(Image: Liverpool Echo)

Nichola Anne with records from her time spent in care(Image: Liverpool Echo)

However, there have also been those who have lodged objections about the children themselves, often based on misconceptions and well-worn prejudices.

In some instances, when residents hear a children’s home might be opening on their street, the reaction is often the same: polite objections about “protecting the community” or “preserving the area’s character.”

But beneath the planning jargon lies a quieter fear, that children in care are problems waiting to happen.

Nichola Anne knows this prejudice all too well. She said: “People talk about us like we’re dangerous but we weren’t bad kids. We were broken kids. We were just trying to survive.”

Nichola is 45 and settled in Ainsdale, but grew up across the West Midlands during the 1980s and 90s, and was in and out of foster placements.

Her childhood was defined by instability and feeling constantly unsafe, left exposed by a system that too often looked away.

She said: “I think if people knew what had already happened to most of us before we ever saw the inside of a children’s home, they wouldn’t be so quick to judge.”

Nichola’s earliest memories are of shouting, slamming doors and the sound of her mother crying. She does not speak to her father. “He was meant to come every weekend. I’d sit by the window waiting for him. But he never came back.”

Nichola Anne with her sister – you can see the labels number 46 and number 47 which were used to identify them (Image: Liverpool Echo)

Nichola Anne with her sister – you can see the labels number 46 and number 47 which were used to identify them (Image: Liverpool Echo)

Her mother struggled with mental illness and alcohol dependency. Nichola recalls being left alone for hours. “I didn’t understand what was wrong with her,” she says. “I just knew she wasn’t there.”

At seven, she was taken into care for the first time, “We didn’t know what was happening,” she says, “One day we were told we were going somewhere safe. That was all.”

The foster family she stayed with were kind. “For the first time, I felt like I could sleep without being scared,” she says. But the arrangement lasted only six weeks. “Then we were sent back home, to the same chaos. Nothing had changed.”

Not long after, she was removed again. Nichola remembers her mother hiding and then disappearing when the social workers came: “She didn’t say goodbye,” Nichola says softly. “That was the moment I stopped trusting anyone.”

Over the next decade, Nichola was moved to foster homes and sent to live with extended family members. When her adoptive father died suddenly a few years later, everything collapsed: “He was the only one who ever made me feel safe.”

By her mid-teens, Nichola was really struggling and felt increasingly vulnerable, out of control and severely depressed. She was exposed to things no child should ever have to experience. Nichola recounts incidents when she was beaten, emotionally and psychologically abused and the terrifying and traumatic moment she was sexually assaulted.

She said: “For a long time, I was told I was the problem and I internalised that. That’s what the system taught me, if things went wrong, it must be my fault.”

She left care carrying shame that wasn’t hers. It took years, and therapy, to understand what happened was out of her control: “I used to think if I’d just been quieter, better behaved, maybe I’d have been loved,” she says. “Now I know I was a child. I deserved to be loved anyway.”

Nichola Anne at home in Ainsdale(Image: Liverpool Echo)

Nichola Anne at home in Ainsdale(Image: Liverpool Echo)

Sadly, Nichola’s story is not unique. Across England, more than 83,000 children are currently in care, the highest number on record. Many share her experience of instability and stigma.

“People see headlines about crime or troubled teenagers and assume that’s what care is,” Nichola says. “But most of us ended up there because of what adults did to us, not because of what we did to anyone else.”

That stigma, she believes, still drives opposition to children’s homes. “When people fight against a home opening near them, they don’t realise they’re fighting against a child like me.”

Campaigners agree. Children’s charities have long warned that planning objections often delay or derail vital placements. In 2023, Care Leaver Local Offer wrote to the Housing Minister to raise the issue.

It wrote: “Negative and unfounded objections based on prejudices against care-experienced people are commonplace, further exacerbating their feelings of marginalisation and unworthiness.”

Councillor Marion Atkinson, Leader of Sefton Council, said: “The key thing to all of this is that we must have open and honest conversations in our communities – I’m sure we would all agree that it’s vitally important that we take care of the most vulnerable in our society, whether that be people who find themselves homeless, children who need to be taken into care or our armed forces veterans who are adapting back into civilian life.

“But when there are plans for a new children’s home, or a place for homeless people to stay, people can quickly jump into judge and say ‘we don’t want that here’. Sometimes that is because proposals may come as a surprise to people or they are fearful of what impact it might have – but if we’re explaining things and talking to people in our communities they will become more understanding.

“These young people deserve the same respect, dignity and opportunities as any other child. The voices of those with lived experience are powerful in challenging these misconceptions and showing the positive impact care can have.”

“The phrase you sometimes hear is it takes a village to raise a child and that’s so true – if we’ve got children who need our help and support as a society then we should all be doing what we can and instead of making judgements about people or facilities let’s take the time to understand them so we can make informed decisions together and as a council we will support that whenever we can.”

For Nichola, that message hits close to home. “Every move chips away at you,” she says. “You start to believe you’re unwanted everywhere.”

Now, decades later, she is determined to use her story to change minds. “For a long time I was ashamed,” she says. “I thought if people knew I’d been in care, they’d see me differently. But I’ve realised the only way to change that is to talk about it.”

Nichola pauses. “I just want people to see us as human beings. We weren’t bad kids, we were children who needed help.”

Her hope now is that by sharing her story, she can shift perceptions, even slightly. “If one person reads this and thinks twice before judging a child in care, then it’s worth it,” she says. “Because none of us should have to feel like a problem to be solved. We were never the problem.”