The geographical map of Eurasia is once again forming competing blocs. On one side exists the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation (SCO), led by China and Russia, which includes Central Asian countries and Iran, while North Korea – not an SCO member – has moved into strategic alignment with the China–Russia axis. Such a grouping serves as a counterweight to Western alliances.

On the other side, in Northeast Asia, security cooperation among the United States, Japan and South Korea has emerged as one of the most important bulwarks in the Indo-Pacific. The Camp David Summit of 2023, which institutionalised trilateral security cooperation, showed that this framework went beyond ad hoc dialogue. However, the mechanism remains vulnerable, caught between domestic political pressures in Tokyo and Seoul and periodic doubts about US commitment.

The key task for policymakers is to ensure that this trilateral cooperation develops into a durable security framework that could effectively deter and, if necessary, defeat the SCO’s collective coercion.

US–Japan–South Korea cooperation lacks sufficient institutionalisation. Despite the meaningful outcomes at Camp David, the mechanism still heavily depends on Washington’s leadership and does not function as an independent structure. The absence of a direct security pact between Japan and South Korea creates a strategic vacuum that could be exploited by Beijing, Moscow and Pyongyang.

Nevertheless, the fundamentals are strong. The three countries possess state-of-the-art missile defence systems, blue-water navies, and formidable air power, supported by trillions of dollars in defence budgets over the next ten years. If properly coordinated, such assets could forge a multi-layered deterrence structure that no adversary would dare to challenge.

The key task for policymakers is to ensure that this trilateral cooperation develops into a durable security framework that could effectively deter and, if necessary, defeat the SCO’s collective coercion. To find useful, applicable historical lessons on how such a structure could be developed, we should look to the evolution of the Triple Entente prior to the First World War.

This history provides a striking similarity. In the early 20th century, the United Kingdom, France and Russia confronted a rising Germany. Initially, the United Kingdom and France did not share a formal defence treaty. Instead, they gradually built trust and interoperability through incremental agreements, including the 1904 Entente Cordiale and subsequent staff talks.

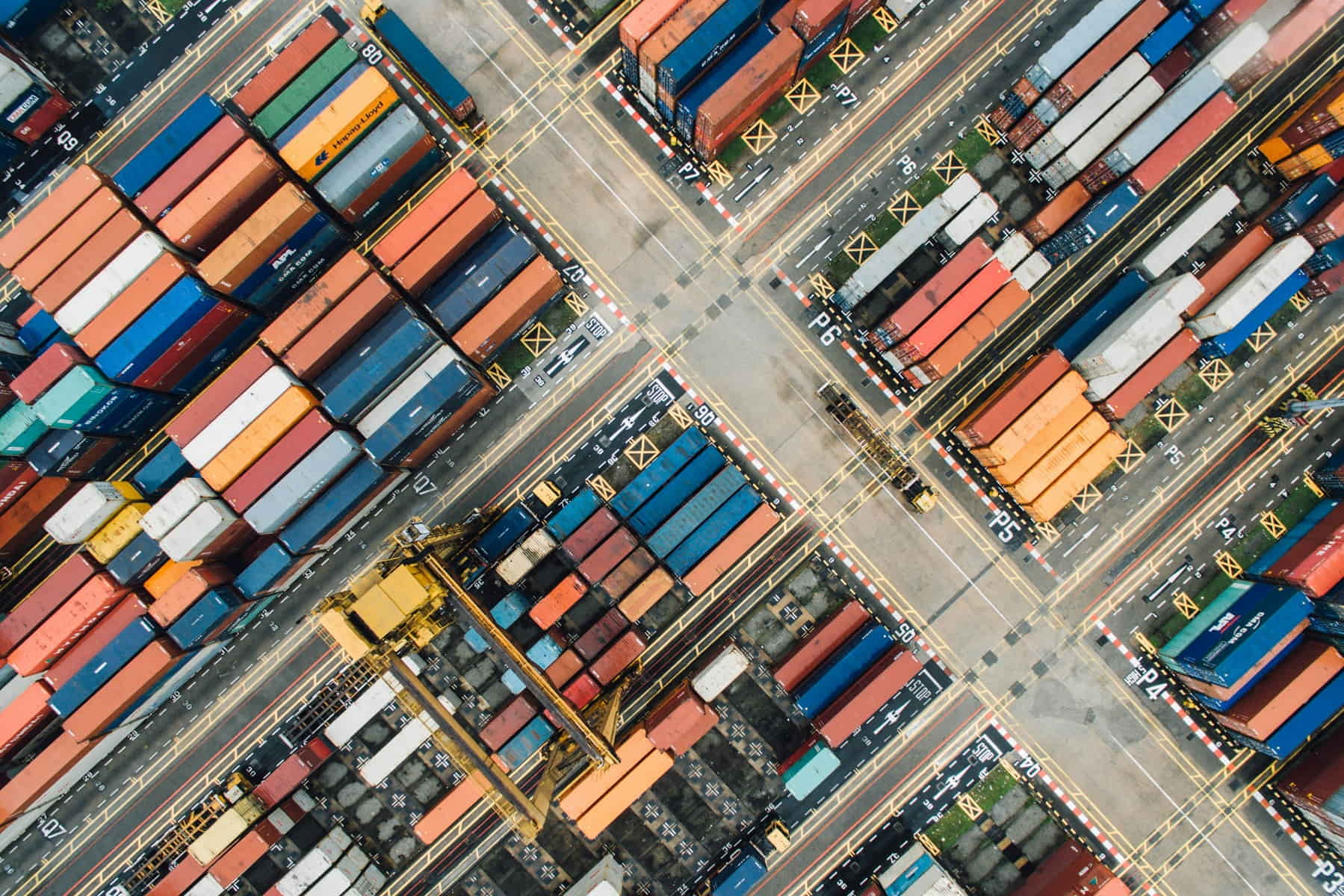

Economic and technological linkages should be internalised between the United States, Japan and South Korea to achieve supply chain security (Chuttersnap/Unsplash)

Such an evolutionary process is a lesson for today. The Triple Entente was not designed as a rigid alliance. Instead, it was an adaptive coalition that gradually institutionalised its response to Germany’s aggressive manoeuvres.

Likewise, US–Japan–South Korea cooperation should be understood as an evolving entente rather than a static structure – one that could deepen its institutional ties while managing domestic political sensitivities over time.

How could Washington, Tokyo and Seoul transform this embryonic entente into a strong pillar of Indo-Pacific security? Several steps are essential.

First, the three countries should institutionalise joint planning. The Triple Entente was able to function thanks to regular military staff talks. The United States, Japan and South Korea should create a constant joint planning group that could prepare for crises, including a dual contingency involving full-fledged wars in the Taiwan Strait and on the Korean Peninsula.

Second, combined exercises should be expanded. Beyond missile tracking, they need to conduct multi-domain operations, including anti-submarine warfare, cyber defence, and integrated missile defence. This could create habits of cooperation that transcend political cycles.

Although the SCO bloc is not a unitary actor, its growing level of integration reflects a shift towards sharper bloc politics.

Third, a joint command mechanism should be developed. Although the Triple Entente lacked a unified command, it effectively coordinated through the Supreme War Council in 1917. Today’s trilateral cooperation could achieve a similar objective by introducing a standing maritime coordination cell or a rotational combined command structure. Such measures could guarantee interoperability without requiring an immediate treaty obligation.

Lastly, economic and technological linkages should be internalised. Just as the United Kingdom and France utilised industrial cooperation, today’s three countries should integrate supply chain security, semiconductor collaboration, and defence-industrial integration. This would create resilience not only in the defence domain but also in the broader systemic context vis-à-vis the SCO bloc.

The risk of a dual contingency – China’s invasion of Taiwan and North Korea’s military provocation against South Korea occurring simultaneously – is no longer hypothetical. As the Atlantic Council wargame results indicate, such a scenario could seriously impact US power if alliances do not act cohesively.

By treating the trilateral framework as a modern entente, the United States, Japan and South Korea could bridge the credibility gap regarding extended deterrence, reassure domestic publics, and clearly signal to Beijing, Moscow and Pyongyang that coordinated aggression would be met with coordinated defence.

Although the SCO bloc is not a unitary actor, its growing level of integration reflects a shift towards sharper bloc politics. In response, the US–Japan–South Korea framework should not remain a loosely connected mechanism. Like the Entente Cordiale, it should gradually develop into an institutionalised structure – one that transforms shared interests into a shared strategy.

As history demonstrates, if an entente can adapt to evolving threats and promise gradual consolidation, it can offer effective deterrence similar to that of a formal alliance. The current task is to ensure that trilateral cooperation in Northeast Asia does not remain an experiment but matures into a central pillar of deterrence in the Indo-Pacific.