The DSEI UK booth of the UK Royal Navy, which promoted at the expo its Portsmouth Capability Accelerator for the rapid acquisition of innovative technologies.

The DSEI UK booth of the UK Royal Navy, which promoted at the expo its Portsmouth Capability Accelerator for the rapid acquisition of innovative technologies.

John Jacobs, Ph.D.

Analyst, NSBT Japan

At DSEI UK 2025, one of the world’s largest defense industry exhibitions held at the Excel Centre in east London from September 9 to 12 and attended by NSBT Japan, key issues discussed by political, military and business leaders were how to guarantee more agile and rapid acquisition of defence equipment and technology and how to make supply chains more secure.

Numerous conferences at the show were reserved not only for discussions on the salient challenges facing defense procurement and supply chain resilience, but also the highlighting of new innovative initiatives being pursued by governments, militarities and industry in order to address such key issues.

British Initiatives: A New Defence Industrial Strategy & Capability Accelerators

A consistent message voiced at this year’s DSEI UK by the political leadership in the United Kingdom (UK) was the need to invest in Defence as an “engine for growth” and to achieve fast, efficient, and agile procurement in order to secure the “warfighting readiness” of the country’s armed forces amid an increasingly volatile international security environment.

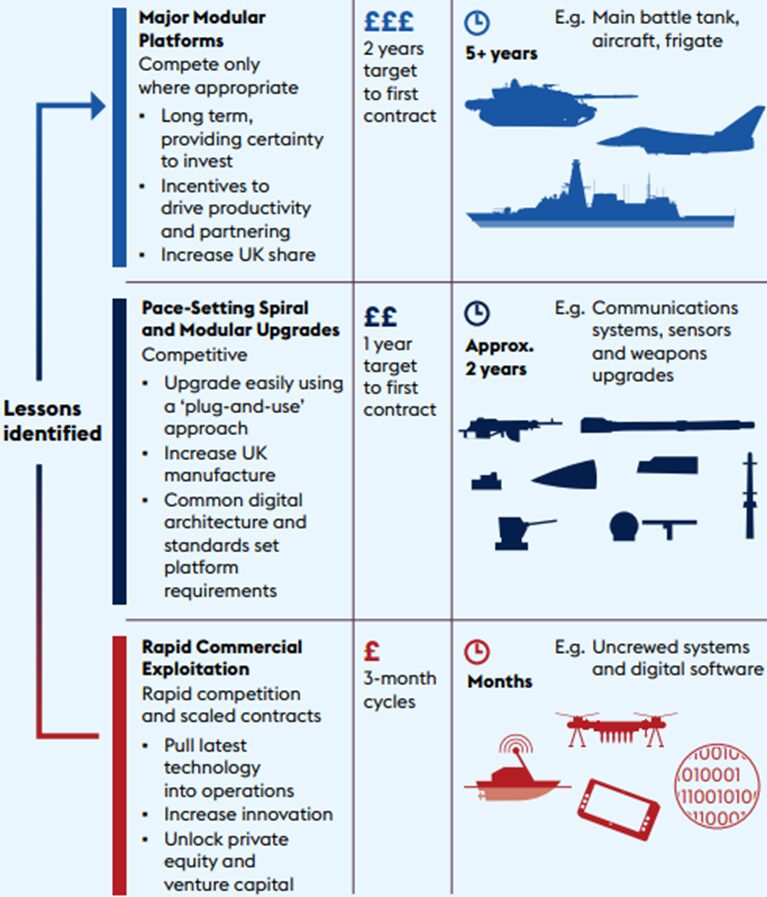

A day prior to the opening of DSEI UK, the UK government published on September 8 its long-awaited Defence Industrial Strategy (DIS). The new document commits the government to “REFORM procurement, INNOVATE at wartime pace, and GROW [the] industrial base.” In the DIS, Secretary of State for Defence John Healey MP highlights a new £250 million investment designed to create new jobs and opportunities in support of a “defence dividend” shared across the UK, as well as a pledge to “make it easier for British-based firms – including SMEs – to do business with the MOD”.[1]

Three main procurement streams envisioned by the UK’s Defence Industrial Strategy, September 2025.

Three main procurement streams envisioned by the UK’s Defence Industrial Strategy, September 2025.

In a DSEI UK keynote address on September 10,[2] the recently appointed UK Minister of State for Defence Readiness and Industry, Luke Pollard MP, highlighted the need for UK MOD to speed up its procurement and contracting processes, and to quickly acquire relevant emerging technologies that are innovative and agile. This in turn requires a cultural shift in the ministry’s approach to risk ratios in contracting to reflect a volatile security environment that is between peace and war.

The minister noted that DIS’ objective is to establish an agile defense industry in support of a UK armed forces capable of contributing to the warfighting deterrence of an “alliance of nations”. In this regard, while the UK’s Strategic Defence Review (SDR) asserts that “NATO first” is expected to represent the UK’s primary area of operations as being in the Euro-Atlantic, Pollard stressed this does not preclude an active UK role in the wider world, referencing in particular the Carrier Strike Group (CSG) deployment to the Indo-Pacific.

Luke Pollard MP, UK Minister of State for Defence Readiness and Industry, taking questions after his keynote speech at DSEI UK, September 9, 2025.

Luke Pollard MP, UK Minister of State for Defence Readiness and Industry, taking questions after his keynote speech at DSEI UK, September 9, 2025.

Nevertheless, while the newly released DIS aims “to make the UK the best place in the world to start and grow a defence business,”[3] Pollard nevertheless acknowledged the presence of significant barriers to industry engagement with the UK MOD. Most notably, the minister recognized that UK MOD was too slow and needed to speed up its procurement, learn to adopt a culture that accepts greater risk-taking and the implementation of a “spiral development” procurement model[4] in order to achieve both warfighting readiness and economic growth.

At this year’s DSEI, political messaging regarding the UK forces’ continuing international role and the need for reform to facilitate agile procurement was also highlighted by the UK’s top military leadership. In a Naval Forum panel on September 9,[5] UK Royal Navy Commodore Marcel Rosenberg, Commander of the Naval Base in Portsmouth, highlighted the modern day Royal Navy’s international orientation, as exemplified by ther service’s leadership of the world-wide deployed multinational CSG.

Commodore Marcel Rosenberg, Commander, H.M. Naval Base, Portsmouth – Royal Navy, speaking at DSEI UK on September 9, 2025.

Commodore Marcel Rosenberg, Commander, H.M. Naval Base, Portsmouth – Royal Navy, speaking at DSEI UK on September 9, 2025.

Commodore Rosenberg went on to highlight how the new DIS seeks to establish a new partnership between government, industry, workers and the armed forces to revolutionize the delivery of defense capabilities.

In the navy context, a key initiative highlighted was the recent establishment of a “Capability Accelerator” at Portsmouth Naval Base. Described by the Commodore as an “alternative acquisition pathway” developed in partnership with Defence, industry and academia to exploit commercial off-the-shelf capabilities, the Accelerator is “delivering the [DIS]” through its focus “on short-life cycle, innovative capability, software, equipment, agile and rapid delivery with a focus on autonomy”.[6]

The Royal Navy’s objectives for the new Accelerator include streamlining the acquisition process, facilitating industry’s early engagement with decision-makers, and to reduce barriers of entry for small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs). Thus, the Portsmouth-based initiative has been structured like a pre-approved club and will feature company membership that goes beyond those firms that are currently contract holders with the UK MOD in order to provide opportunities to address the challenges faced by Defence.

Commodore Marcel Rosenberg highlighted three pilots currently active in the HMNB Portsmouth Capability Accelerator’s first hundred days that are designed to “cut a path through the jungle of process”. The first pilot relates to a project involving the service’s “Navy PODS (Persistent Operational Deployment System)”. These “PODS” are essentially shipping containers designed to house vital interchangeable modules that can quickly be fitted to warships when needed.[7]

Exterior and interior views of a Royal Navy Persistent Operational Deployment System (PODS) fitted with medical equipment, March 2024.

Exterior and interior views of a Royal Navy Persistent Operational Deployment System (PODS) fitted with medical equipment, March 2024.

The second Portsmouth Capability Accelerator pilot relates to small unmanned surface vessels (USVs) currently being trialled with the Royal Navy’s CSG with the aim to bring their use to scale. The final project relates to an AI learning tool related to “SAGA” (Scenario Automated Generation using AI)[8] that is designed to identify potential solutions to operational problems and is already deployed at sea. The aim now is to bring this AI tool to scale through the Portsmouth Accelerator.

Ukrainian Wartime Initiatives: Digital Marketplaces for Agile Acquisition

Nevertheless, it was clear at this year’s DSEI UK that it is in Ukraine where the necessity of fending off Russian aggression has become the mother of all inventions when it comes to agile and rapid procurement.

On the third day of the expo on September 11, Arsen Zhumadilov, Director of the Defense Procurement Agency of Ukraine within the Ministry of Defence, explained how Kyiv’s agency has split its procurement system concerning direct commercial sales and tenders with international defense companies into two distinct streams.

The first more conventional stream requires long-term planning and is reserved for long-term contracts signed by the Defense Procurement Agency and tailored for traditional armaments, ammunition, tanks and so on. Meanwhile, the second more rapid and agile procurement stream is reserved for those “game-changing” products that have short innovation cycles that render traditional long-term contracts and centralized stockpiling approaches difficult.

Arsen Zhumadilov, Director of the Defense Procurement Agency of Ukraine addressing DSEI UK, September 11, 2025.

Arsen Zhumadilov, Director of the Defense Procurement Agency of Ukraine addressing DSEI UK, September 11, 2025.

Zhumadilov explained how, in the second stream many capabilities, particularly unmanned vehicles, electronic warfare devices and autonomous systems, have innovation cycles that are too short for long-term procurement cycles used in the first traditional stream. Ukrainian troops on the battlefield need to make sure that they have ready access to the most cutting-edge products among these in order to stay ahead of the Russian adversary.

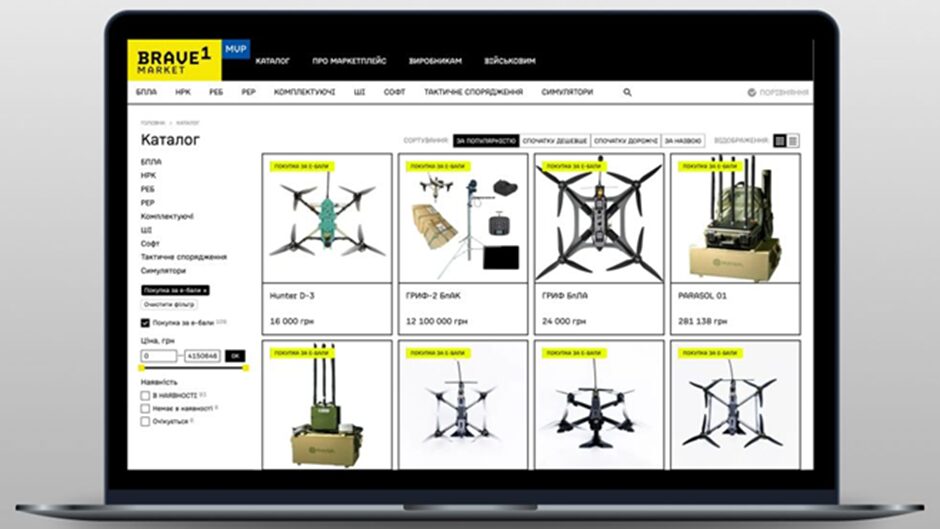

The fast-tracked procurement stream consists of two digital platforms, “DOT-Chain Defence” and “Brave1”.[9] These are “Amazon-like” consumer-driven competitive online marketplaces in which Ukrainian military end-users, including brigades, battalions and companies, act directly as consumers and defense suppliers as their sellers. Consumers on the frontline choose directly the products they need and then the Defense Procurement Agency does the bureaucracy and contracting. This has reduced lead times to 2 weeks on average and in exceptional cases it took only 5 days for a product to be ordered and delivered to the frontline.

In total, 500 million hryvnias (approx. 12.2 million USD)-worth of equipment has been supplied through DOT-Chain Defence. Meanwhile, a total of 95 Ukrainian units have ordered “more than 30,000 FPV drones, strike drones and other equipment worth 2 billion hryvnias [approx. 48.8 million USD] through the Brave1 Market”.[10]

Logos for Ukraine’s DOT-Chain Defence (left) and Brave1 (right)

Logos for Ukraine’s DOT-Chain Defence (left) and Brave1 (right)

Ukraine’s Defense Procurement Director Zhumadilov stressed that the digital marketplaces are reserved for products with a competitive market, thus ruling out those capabilities that have a more fixed number of suppliers, such as air defense, and those where consumer-choice is not so relevant, such as ammunition.

Instead, market focus is on those products that have a competitive supply and for which there is a well-informed consumer choice on the demand side among Ukraine’s units. In addition to unmanned vehicles and electronic warfare devices, Zhumadilov noted that Ukraine’s digital marketplaces might soon be expanded to include warheads for drones and interceptor drones on the condition that market structures for such products are in place.

Image of the “Amazon-like” Brave1 digital marketplace.

Image of the “Amazon-like” Brave1 digital marketplace.

Zhumadilov explained that there is a low barrier to entry for firms to get products on to the Ukrainian online marketplace. To be eligible for sale, products need to be codified by the Ukrainian MOD to make sure they work well. Meanwhile the Procurement Agency is responsible for checking the legal entity selling the product, including its financial stability and whether it is associated with a country under international sanctions, such as Russia, North Korea, Iran and Belarus.

Zhumadilov stressed that this is not a high threshold for companies to meet and can be done in as little as 2 to 3 weeks. However, although this barrier to entry is quite low, he acknowledged that receiving actual orders from the frontline brigades is more difficult due to their demanding requirements regarding service levels from a given company and its products. Of around 159 products on the marketplace, only about one third receive some orders. In turn, the top five producers and devices on the platform make up a large chunk of all orders made.

Ukraine is now sharing this digital marketplace approach with like-minded countries so they can learn from this approach. To this end, the U.S. Army is one such partner that has recently committed to opening up its own internal “Amazon-like” marketplace for UAS.[11]

Nevertheless, it is also important to note here that Brave1 is not just an online marketplace. As a defence cluster, it includes universities in order to enable them to contribute to the science of defense solutions, to facilitate consultations with academic experts for developers, and to arrange job and skills opportunities for students.[12] Brave1 also provides grant and investment support, and acts as a “soft-landing” for overseas partners by guiding them through the Ukrainian MOD codification process and to facilitate testing in the country.[13]

A Private Sector-led Initiative: “Defence as a Service”

Another novel approach to procurement discussed at DSEI UK 2025 was “Defence as a Service” (DaaS),[14] which essentially conceptualizes acquisition as a subscription service akin to the cloud-based “Software as a Service (SaaS)” used in the IT sector in which customers pay for access to an online service rather than owning a copy of it outright.

At the London expo, this service-driven approach to defense was advocated by Andy Baynes, Chief Strategy Officer and Co-Founder of Tiberius Aerospace Inc.; a defense startup that has adopted a distributed model with engineering hubs located in the UK, U.S. and Australia and manufacturer of the “SCEPTRE” guided ramjet liquid fuelled munition known for its economical deep-strike capabilities.

Tiberius Aerospace explains on its website that DaaS aims to separate “R&D from manufacturing, enabling rapid iteration, sovereign scalability, and continuous innovation on a global scale.”[15] The approach aims to overcome defense’s reliance on “slow, rigid, and expensive” OEM systems offered by prime contractors in favor of an “agile methodologies and platform-agonistic design” that allows for “third-party manufacturing, modular upgrades, and real-time optimization.”[16]

Tiberius’ DaaS business model consists of the following philosophies and approaches:

- Continuous Design: Weapon systems that can be improved iteratively with minimal downtime through the use of open architectures.

- Open Manufacturing: Decoupling of the design phase from production lines to enable third-parties to fabricate the technology locally in their own regions.

- IP-Licensing: Sovereign-controlled manufacturing and pooling of development costs without comprising company IPs or interoperability.

Tiberius’ Baynes explained that his own pursuit of this DaaS model was inspired by his experience of working in Silicon Valley to consider how in the context of defense Tiberius could inject speed into continuous iteration in support of open architecture designs. To illustrate this, reference is made to the iPhone as a consumer electronic device that has succeeded in being at the top of its class for 17 years and benefited from quickly implementing iterative software and hardware upgrades over a long period of time.

Turning to the business advantages of DaaS, Baynes asserts that the model can help eliminate defense’s boom and bust cycles typical of single-use systems experienced by primes and instead enable companies to generate recurring revenues through subscriptions. This in turn can help companies attract capital investment. At the time of writing, Tiberius’ website lists as DaaS participants a total of 13 innovation partners, 25 manufacturing teams, and 56 components.[17]

“Defence as a service” panel at DSEI UK featuring Tiberius Aerospace Chief Strategy Officer and Co-Founder Andy Baynes (far left), September 10, 2025.

“Defence as a service” panel at DSEI UK featuring Tiberius Aerospace Chief Strategy Officer and Co-Founder Andy Baynes (far left), September 10, 2025.

Baynes went on to explain how Tiberius’ SCEPTRE missile, which is in use in Ukraine and capable of delivering payloads in excess of 150km launched from a 155mm howitzer, has been a beneficiary of an open architecture approach.

This methodology has enabled Tiberius to build up a diverse and resilient supply chain in which any third party can easily attach their kit to a Tiberius bus. He described this approach as akin to a modular PC workstation in which one can easily attach new graphics or WiFi modules in order to extend their relevance.

Conclusion

At this year’s DSEI UK, attended by the NSBT Japan team, military and political leadership along with the private sector consistently emphasized the volatile security environment beset by fast-paced technological and geopolitical changes. As a result, the UK MOD in particular is particularly reflecting on its internal cultural practices that have for years supported an old, slow and long-term approach to procurement in the face of this environment. Both industry and the public sector are thus actively exploring new initiatives explored in this article by which they can speed up the acquisition process to meet the challenges of today and prepare for the future.

Notes:

[1] UK Ministry of Defence, “”Defence Industrial Strategy: Making Defence an Engine for Growth”, p.6, https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/68bea3fc223d92d088f01d69/Defence_Industrial_Strategy_2025_-_Making_Defence_an_Engine_for_Growth.pdf.

[2] UK Government, “Minister Pollard speech at DSEI”,https://www.gov.uk/government/speeches/minister-for-defence-speech-at-dsei.

[3] Ibid.

[4] The spiral model of procurement is described by UK MOD as “Delivering a minimum deployable capability quickly, and then iterating it in the light of experience and advances in technology – rather than waiting for a 100% solution that may be too late and out of date.”

https://commonslibrary.parliament.uk/research-briefings/cbp-9566/.

[5] DSEI UK 2025, “Support as an accelerator for the maritime economy enabling the Royal Navy to operate and fight with confidence”, September 9, 2025, https://www.dsei.co.uk/dsei-2025/organic-resilience-fleet.

[6] Fore more on the Portsmouth Capability Accelerator, also see: John Hill, “Royal Navy autonomy centre in Plymouth, accelerator in Portsmouth”. Naval Technology, June 30, 2025, https://www.naval-technology.com/news/royal-navy-autonomy-centre-in-plymouth-accelerator-in-portsmouth/.

[7] Royal Navy, “Maritime Modularity Concept”, 2022, https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/63dcece38fa8f57fc8061089/Maritime_Modularity_Concept.pdf, p.26.

[8] SAGA referenced here is most likely the acronym for an AI model called “Scenario Automated Generation using AI”m which is discussed in detail in: John Hill, “DSET 2025: Nato disclose priorities in modelling and simulation”, July 10, 2025, https://www.naval-technology.com/news/dset-2025-nato-disclose-priorities-in-modelling-and-simulation/.

[9] For more on DOT-Chain Defence, see: Ministry of Defence of Ukraine, “Ukraine launches DOT-Chain Defence – a digital system for rapid delivery of weapons”, July 7, 2025, https://mod.gov.ua/en/news/ukraine-launches-dot-chain-defence-a-digital-system-for-rapid-delivery-of-weapons. For more on the Brave1 platform, see: https://brave1.gov.ua/en/.

[10] BRAVE1, Linkedin Post, https://www.linkedin.com/posts/brave1ukraine_first-ew-systems-ordered-with-e-points-are-activity-7369324069739044867-7Uk4.

[11] Zach Rosenberg, “US Army to open internal UAS Marketplace website”. Janes, August 12, 2025, https://www.janes.com/osint-insights/defence-news/defence/us-army-to-open-internal-uas-marketplace-website.

[12] BRAVE1, Linkedin Post, https://www.linkedin.com/posts/brave1ukraine_the-first-seven-universities-have-joined-activity-7369734495014526978-dHgy.

[13] Benjamin Howe, “Ukraine’s Brave1 highlights progress, invites collaboration”. DSEI Gateway News, April 28, 2025, https://www.dsei.co.uk/news/feature-ukraines-brave1-highlights-progress-invites-collaboration.

[14] DSEI UK, “Defence as a service: Continuous innovation – decoupled manufacturing”, September 10, 2025, https://www.dsei.co.uk/dsei-2025/tbc-w0zc.

[15] Tiberius Aerospace Inc., “About Us”, https://www.tiberius.com/about-us.

[16] Tiberius Aerospace Inc., “Defense as a Service: Continuous Innovation – Decoupled Manufacturing”, https://www.tiberius.com/daas.

[17] Ibid.

This article was originally posted on NSBT Japan, the first defense and security industry network in Japan. The publication provides the latest information on security business trends both within Japan and overseas. Asian Military Review began exchanging articles with NSBT Japan in April 2024.

Read the original article here.