London isn’t building enough houses. In fact, it’s hardly building any at all. There were only 6,000 new home sales in the capital during the first half of 2025, according to research company Molior. Annualised, this is a mere 90 per cent shortfall in the government’s 88,000 annual target for the capital.

This is set to get worse before it gets better, despite the government’s ambitions to ease planning constraints via its upcoming National Planning Policy Framework. The same research finds there were just 3,250 starts during the same period. Clearly, if the capital is going to address its severe housing shortage and propel the wider UK economy, something has to change.

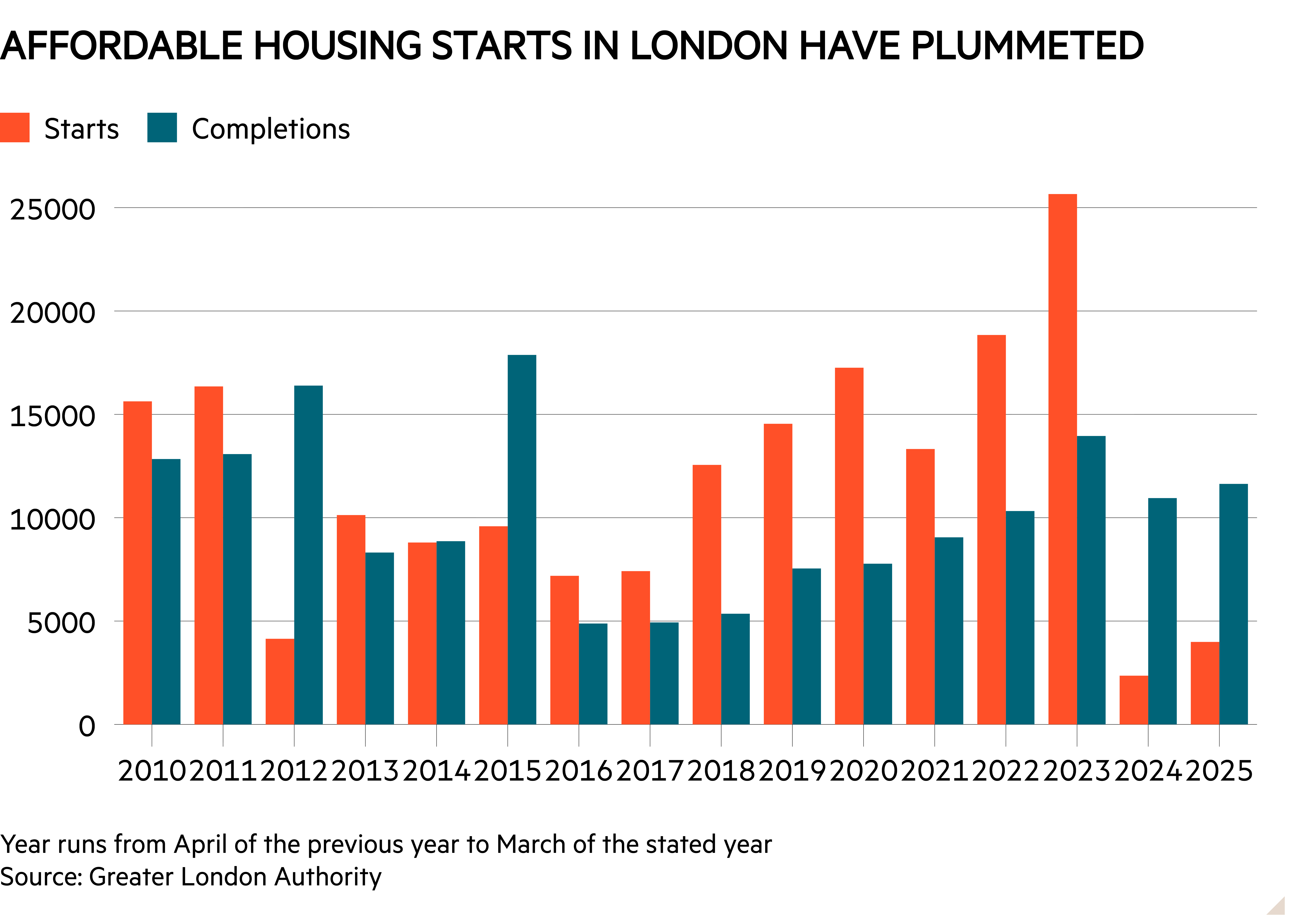

Is that something affordable housing quotas? The Financial Times has recently reported that the Greater London Authority (GLA) is considering lowering its standard quota from 35 per cent in order to stimulate more development. Yet in isolation this is unlikely to be enough.

Read more from Investors’ Chronicle

The need in the capital for affordable housing – housing for those whose needs cannot be met by the open market – is acute, with demand far outstripping supply. You can understand why, shortly after his election, London mayor Sadiq Khan established a 35 per cent affordable housing quota for any development looking to be fast-tracked through planning.

But you can have too much of a good thing. Housebuilders “are in effect selling these homes at a 30-40 per cent discount to market value”, says Anthony Codling, analyst at RBC Capital Markets. A higher quota reduces a development’s profitability and may discourage housebuilders such as Berkeley Group (BKG) from proceeding with projects.

It doesn’t help that local authorities are currently too cash-strapped to issue grants that can help get developments over the line (the £39bn recently allocated to affordable housing by the government will take time to filter through).

Reducing the quota to 20 per cent, broadly in line with the national average, should make development more appealing. But this in isolation is unlikely to be the silver bullet the industry needs. “It is difficult to disaggregate it [the quota] from other factors [hindering development],” acknowledges Investec analyst Aynsley Lammin.

“We need a more flexible approach to ensure sites are viable to bring more forward, but affordable housing levels are not the only issue,” said Steve Turner, executive director of the Home Builders Federation. “There’s huge delays as a result of the BSR [building safety regulator], while the London Plan has a number of requirements over and above other areas of the country.”

The building safety regulator has to sign-off on all developments of 18 metres or higher, a ruling introduced in response to the Grenfell Tower fire. Insufficient staffing has resulted in delays of over nine months, deterring capital providers from financing development.

The London Plan requires these developments to have second staircases and apartments with windows on at least two sides. This significantly reduces the floorspace that can be built and sold on to homebuyers.

Then there is lukewarm demand. This is largely the result of affordability constraints, with the average London property costing nine times the median salary (it is six times in the UK as a whole). The reintroduction of Help to Buy or a similar scheme may be needed here.

“The mayor is determined to work hand-in-hand with the government to support their ambition to get Britain building again,” said a spokesperson for the mayor. “We are making significant progress.”