Mother Jones illustration; Portrait by Emily Kassie

Get your news from a source that’s not owned and controlled by oligarchs. Sign up for the free Mother Jones Daily.

In May 2021, ground-penetrating radar detected more than 200 unmarked graves of Indian children near the former Kamloops Indian Residential School in British Columbia, Canada. The discovery prompted US Secretary of the Interior Deb Haaland to announce the Federal Indian Boarding School Initiative, an investigative review of the legacy of Indian boarding schools in the United States.

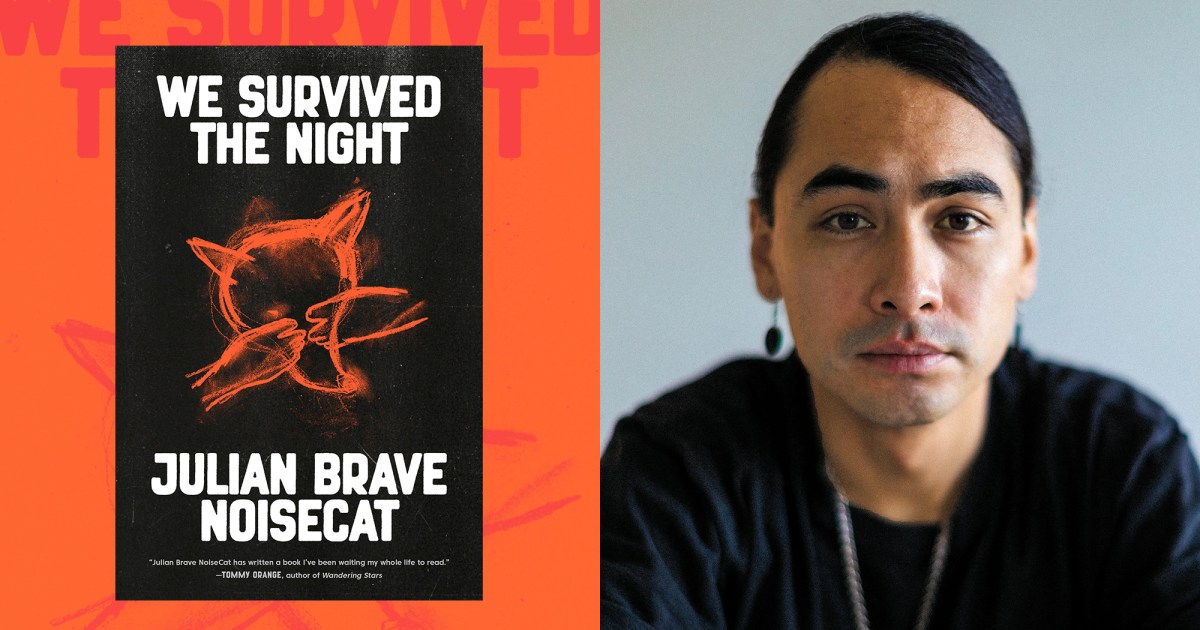

While both countries attempted to grapple with this era in their histories, Indigenous families continued grieving the loved ones, culture, and tradition lost to Indian residential schools. In We Survived the Night, the writer and filmmaker Julian Brave NoiseCat grapples, in part, with this legacy and its impact in his own family and community. NoiseCat previously explored this territory in Sugarcane, the 2024 Oscar-nominated documentary, which follows the Williams Lake First Nation’s investigation into the abuse at St Joseph’s Mission and the resulting intergenerational trauma.

We Survived the Night begins with the story of NoiseCat’s father, Ed, who was found hours after birth in the trash incinerator at St. Joseph’s Mission, an Indian residential school in British Columbia, Canada, perhaps moments from death. Ed grew up on the Canim Lake Indian Reserve and was part of the first generation there not sent to residential schools. But growing up on the reserve was hard, and NoiseCat writes that his father is “an Indian who barely knows how to live in this world. Just how to survive.”

This book started as a way for NoiseCat to understand and reconnect with his father, who he writes was always “coming and going” from his life. But the memoir also goes beyond his family story, weaving in reporting about Indigenous communities through North America with mythology and oral histories through the story of Coyote, a trickster whose antics are legendary among the Salish people. These Coyote stories were told for generations among NoiseCat’s people, but were largely lost to colonization.

In his reporting, NoiseCat told me he wanted to tell stories about Native people and communities that have been overlooked, but also that say something about the different roles of Indigenous people across North America. He travels to visit the Tlingit in southeast Alaska as they navigate a conflict over herring eggs in the Sitka Sound; to the Lumbee in southeastern North Carolina, who are seeking federal recognition despite pushback from other Native nations; and to a Diné medicine man in Arizona who endured through the Covid-19 pandemic. “Looking out at that big, diverse Indian world is one of my ways of looking within—just as looking within is a way for me to look out,” NoiseCat writes.

I talked with NoiseCat recently about writing We Survived the Night, which he describes as a book dealing with questions of life, death, and survival. “I do believe that there are spiritual dimensions to asking those sorts of questions,” he said. To write it, he told me that he took on more ceremonial commitments in his community.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Can you start by talking about what motivated you to write We Survived the Night?

I’m the son of a noted Native artist and an Irish Jewish New Yorker. My dad left when I was pretty young, and I had a really Indian name—Julian Brave NoiseCat is about as Indian a name as you can have—and I looked the way I looked, yet the father who connected me to my family, my community, and my culture was gone. I was always trying to understand him and why he left, and what it was to be Native, and even more specifically, what it was to be a Native man—a Secwépemc man, a St’at’imc man—and I think that reading and writing was kind of always one of the core ways that I was trying to sort that out—devouring the work of Sherman Alexie and other Native writers: Leslie Marmon Silko, N. Scott Momaday, Louis Erdrich.

One of the things that I found most striking about this book is how much grace you give so many different people in your life. You don’t really vilify anyone, when you certainly could.

I definitely feel some pain about my experience in relationship to my father and other figures in the book. I also think about what my grandfather did—having all those kids and womanizing in the way that he did—and I can see the way that that still hurts my grandmother. Yet I also see the beautiful ways that those men helped make my complicated world and I can’t separate them out.

Some of the same reasons my dad didn’t know how to be a dad and wasn’t present were the same reasons that he’s a survivor and he’s still here. Some of the same reasons he struggles to be a present, empathic father is that he had to look out for himself. That also has led him to be hyperfixated on his art as his way to survive.

I wanted to capture that truth and the way that I see it as honestly as I can. I don’t think that I could spend a lot of time writing about people who I didn’t love. To me, to tell a story about someone is to say, “I have spent so much time with this person or thinking about this person and their story and their life and this is a story that only I could tell you about them.” I see myself in that tradition.

Something that you write about is this idea of feeling like you have to earn the right to your indigeneity. Tell me about this idea of what it means to be Indigenous and how working on this book challenged or changed the way you understand it.

Almost every single Native person I know doesn’t feel, in some particular way, Native enough. We all wish that we spoke our language a little bit better, or were better about spending time in our family or community, or that we were more present in our ceremonial or cultural life. Maybe we wish we had better hair or darker skin—the list goes on.

There’s something about being Native wherein we all feel like we’re not necessarily Indian enough and that’s because the history of being Native—which is a term that only makes sense in the context of colonization—is one of just immense, immeasurable, unfathomable loss. Two continents were stolen from us. We’re having this conversation in a language that was imposed upon us by colonizers and that makes so much of our life as Native people often an act of reclamation and recovery.

In the writing of the book—and especially while I was working on Sugarcane—I was thinking very purposefully about what traditions as a storyteller I had a responsibility to try to recover and bring back to life. This is what ultimately led me to the Coyote stories, which are these trickster narratives from my people’s culture. As I was reading them, I just kept seeing so much of the stories in my own life, in the Native world, and in the world.

Broadly, it’s hard for me not to look out at the world right now and the news cycle and just be like, this is a world that is deeply shaped by tricksters and their tricks.

I hope that more broadly, people recognize that Indigenous peoples are core to the story of this land, and always have been.

I’m glad you mentioned Coyote. I love him as this character and as a guide through the narrative. Can you talk about how you wove him into these stories?

I moved in with my dad for two years while I made Sugarcane and wrote, We Survived the Night. After not living with the guy for 22 years, suddenly we were across the hallway from each other, hanging out every evening, and I would turn on my recorder and ask him to tell me different stories. We’d laugh, hang out, smoke a little weed, and play board games and stuff. During the day, I’d be working on my writing while he’d be out in the studio carving. I was reading all these oral histories about Coyote and I was just really struck by the parallels between him and Coyote and the stories that I was reporting. Then it just sort of clicked: What if I took that notion—that the Coyote stories are nonfiction—seriously?

I was also honoring what is, to the Salish peoples, probably our most celebrated art form: weaving. My great grandmother and my great-great grandmother were basket weavers. We don’t have any weavers in our family really anymore, but their work is still considered our most prized possessions. So, it also felt kind of appropriate to be telling a story that was itself kind of a woven story and an acknowledgement of the fact that to my people, weaving is the highest art form.

What do you most hope readers take away from We Survived the Night?

I take seriously the notion that a book is also supposed to make you feel things and entertain you, so I hope that the universal aspects of the story—our relationship to our parents, our relationship to tradition, questions of life and death, spirituality, and survival—do that.

You could argue that the system that I’m describing—one that takes away Native kids from their parents and deprives an entire race of people from the right to parent—is an authoritarian system, which is obviously relevant in the present moment. But at its core, the extent to which it is still possible to be a serious intellectual, a serious commentator, a serious historian of North America—someone who supposedly knows this land and its people—and to not know anything really about Indigenous people really irks me. I hope that more broadly, people recognize that Indigenous peoples are core to the story of this land, and always have been. Because we are the first people of it, by understanding us and our stories, you can actually understand this place and this society and this world and what it is to be human, in deeper ways. I do really believe that, and I hope that people get some sense for that.