Gyms overflowing, menus full of small plates and a surge in ‘Ozempic face’ supplements are just a few ways in which weight-loss jabs are altering society

Though weight-loss drugs have only been at large in the UK since September 2023, today, everyone knows someone using it, and everyone has an opinion on whether it is safe, sad or sensible. Novo Nordisk, which produces Wegovy and Ozempic, has become one of Europe’s most valuable companies, revealing profits of $17.8bn (£13.8bn) earlier this year. There seems little doubt that it will reshape the future of various businesses, just as it will people’s bodies.

Mounjaro (produced by Eli Lilly) and Wegovy are the most commonly used weight loss drugs in the UK. Ozempic should only be prescribed to people with type 2 diabetes. But it has been used in the US as a weight loss tool for years, and is increasingly being used ‘off-label’ for this in the UK.

To qualify for Wegovy or Mounjaro via the NHS, patients must have a Body Mass Index (BMI) of 35kg/m2 and at least one pre-existing, weight-related health condition. The drug is expensive and funding is limited: it currently costs the NHS about £3,000 a year to give a patient one of these drugs, and there are 3.4m who are eligible. If we were all to receive it, it would cost £10bn annually, which is half the drug budget for the NHS.

So the majority of users – nine out of 10 – go private, through high street and online pharmacies, for roughly £130 a month for the starting dose, increasing to about £269 a month for the maximum dose. No wonder the Denmark-based Novo Nordisk is singlehandedly shaping the Danish economy.

But to what extent is it shaping ours? With only two years under the belt of these drugs in the UK, data is slim, and opinions differ, but many think this could be seismic for brands, businesses – and even social culture.

Some have predicted the mass use of weight loss drugs could mean a dramatic reduction in fuel bills for the aviation industry, because passengers will be lighter (Photo: Witthaya Prasongsin/Getty Images)

Some have predicted the mass use of weight loss drugs could mean a dramatic reduction in fuel bills for the aviation industry, because passengers will be lighter (Photo: Witthaya Prasongsin/Getty Images)

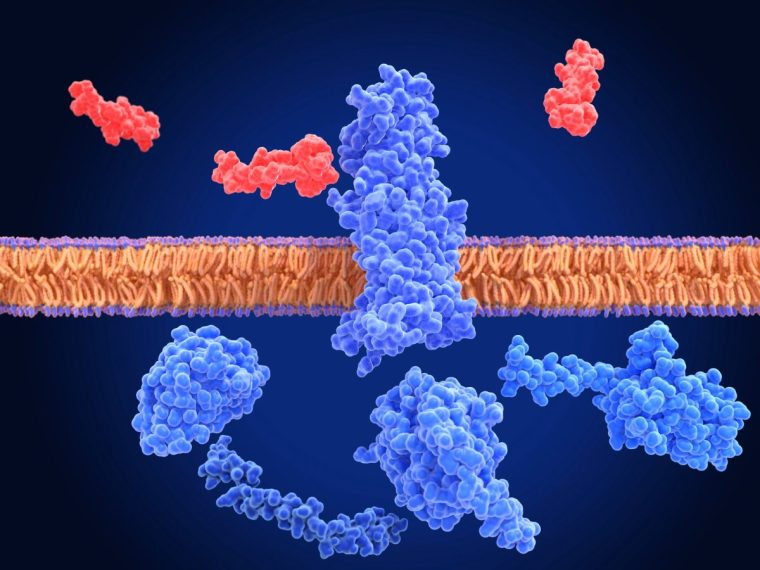

This is not just because people are losing vast amounts of weight, but it is also affecting fashion, psychological and physical health, and the way we socialise. It’s also down to the way these drugs work. Known collectively (and unsexily) as GLP-1 receptor agonists, they mimic hormones in the body responsible for regulating appetite and satiety. Not only do they slow digestion and make users feel fuller for longer, but they also appear to reduce cravings for alcohol and high-fat, high-sugar foods.

There have been no significant studies to prove this, but in a survey of 300 patients in the US, Morgan Stanley found those on the drugs consumed between 20 to 30 per cent fewer calories daily, cut back their consumption of confections, sugary drinks and baked goods by as much as two-thirds – and a quarter quit alcohol.

The potential impacts of these drugs are enormous and range from the restaurant industry to aviation: lighter passengers could wipe billions off the fuel bill. Yet analysts at Barclays told global stock research platform LongPort last year that “investors are currently finding it difficult to assess the comprehensive impact of GLP-1 drugs, as the potential market scenarios are very broad.”

How cheap – and thus how widespread – these drugs could become, their long-term success rates, the side effects they entail, and the extent to which this could yet prove a trend are all significant factors and relatively unknown. Then there are the risks these drugs pose to those who shouldn’t be taking them but are managing to access them anyway, something that, in this country, at least, is set to rewrite the regulation.

These drugs are designed to be used for life, but that is not how they are being used currently, either privately or on the NHS. Anecdotally, one hears of people’ doing a little Ozempic’ before their holiday. A study in the US found that just 40 per cent of patients who filled a prescription for Wegovy in 2021 or 2022 were still taking it a year on. NHS only offers Wegovy for a maximum of two years, and whilst there is no NHS time limit on Mounjaro, which is in the process of being rolled out, funding concerns mean it’s a good decade off from becoming widespread.

This is significant when you consider that in clinical trials, most patients who paused the drugs regained the weight they had lost and found it hard to maintain any lifestyle changes they’d made. Change must be more deep-seated if these drugs are to affect any industry meaningfully.

This is why, for the time being, major companies’ analysts, CEOs, and FOs are relatively cautious in – or refuse to be drawn on – their predictions.

Likewise, while the experts I spoke to in the restaurant, health, wellness, and tailoring businesses have seen changes in their respective fields, they are wary of overstating the impact of Ozempic, but here’s what some of them think.

Half a million people in the UK are taking a GLP-1 drug such as Mounjaro or Ozempic, which mimic hormones responsible for appetite and satiety (Photo: Science Photo Library/Getty Images)Restaurants

Half a million people in the UK are taking a GLP-1 drug such as Mounjaro or Ozempic, which mimic hormones responsible for appetite and satiety (Photo: Science Photo Library/Getty Images)Restaurants

The hospitality industry is already struggling thanks to rising costs and punishing tax increases.

In their report, Morgan Stanley anticipated a “softer demand” for restaurants as the use of obesity drugs increases, and it’s certainly true that fast food outlets face a longer-term risk, with same-store sales growth forecast to fall between one to two per cent, according to the investment bank’s report.

Yet many in the sector feel their impact is being overblown. Larger fast food chains like McDonald’s were already adapting their menus to provide healthier options, and though there have been widespread reports of high chefs designing smaller dishes to cater for semaglutide users, financial pressures mean that this trend has been in motion for some time.

“Some restaurants will already be looking to create smaller sized dishes so that they can continue to offer value for money, and this dovetails with people having smaller appetites,” says Stefan Chomka, editor of leading hospitality magazine Restaurant.

Fitness trainers say the rise of semaglutide drugs has fuelled interest in weight training, as people who’ve lost weight seek to maintain muscle mass (Photo: kupicoo/E+/Getty Images)

Fitness trainers say the rise of semaglutide drugs has fuelled interest in weight training, as people who’ve lost weight seek to maintain muscle mass (Photo: kupicoo/E+/Getty Images)

James Chiavarini owns London’s oldest family restaurant, Il Portico, and the more recent La Palombe, both of which are based in an affluent London area where many are likely to be on semaglutides. Yet, whilst “a lot of regular customers have suddenly dropped several clothes sizes,” he isn’t adapting the menu for them, nor does he see the drugs as an existential threat.

“We are not the kind of place that would see a change in eating habits. Everything here is made from scratch; everything is refined. We’ve seen a trend toward more responsible drinking – but that was happening anyway, and we have more, lower ABV wines in.”

Chiavarini, whose restaurant has been around almost 60 years, has seen more than his fair share of social trends, and is highly sceptical. “We don’t know if this one is going to stick around, or if it will all just blow away with the wind.”

Fitness

At first, personal trainer Jamie Roach thought rising semaglutide usage in his local area might precipitate a decline in numbers at the Cranford Sports Club, where he works in Devon. But if anything, they’ve been good for business. “The big concern, for those on these drugs, is muscle mass loss; the need to maintain and even gain muscle,” he says, “so the two [semaglutides and gyms] work alongside each other quite well.”

What has changed is the nature of the workouts. “Traditionally, we’d prioritise cardio– but if they’re on semaglutides, weight is lost whatever we do,” he points out. “We need to make sure it’s the right weight being lost, and not muscle mass.”

It’s still important to do some sort of cardio, but the priority is weight training – which was already a growing trend in gyms, fuelled by social media and a growing awareness of its importance for long-term health. One trend that might wane as a result is HIT (High-Intensity Training), as those on the drug will have less energy to complete it effectively.

“Intense aerobic exercise can lower blood sugar levels, and when combined with GLP-1 meds, there is a risk this can lead to hypoglycemia and further decrease energy levels,” says Jon Denoris, an exercise scientist and the owner of Club 51 Intelligent Fitness in London, which has developed lifestyle and fitness programmes for everyone from royalty to elite sports performers.

They have clients on semaglutides but will only work with those who have come to those drugs via a medical practitioner and are one of the first gyms to design programmes specifically for people on GLP-1 medications. “The main focus is on resistance training, which encourages the preservation of muscle and also improves metabolic health.”

Health food and supplement industry

“I have been in the food industry for 40 years, and in all my years, I have never seen anything so seismic as this,” says April Preston, global product director at wellness retailer Holland and Barrett. For most of those years, Preston has been involved in developing products in response to trends analysis – but she doesn’t call this a trend. “I call it a movement.”

Where manufacturers and retailers of sugary snacks and drinks might see the rise of the skinny jab as a threat, those selling supplements and nutritionally dense drinks and food see them as a huge opportunity. Preston recently returned from the world’s biggest health and wellness conference in Los Angeles, where “about 50 per cent of supplement brands specifically targeted GLP-1 users,” she reports.

Side effects of weight loss jabs can include hair loss and collagen loss, which is huge news for supplement companies. Last June, Nestlé launched a range of supplements for semaglutide users, including hair and collagen supplements to combat ‘Ozempic face’ – the infamous sagging that comes with facial fat loss. Food behemoth Unilever has also acquired supplement and nutrition companies in recent years. At H&B, sales of collagen supplements have increased, as have products supporting healthy hair and skin.

Then there’s the Ozempic-fuelled changes in tastes and drive toward what Preston calls ‘nutritional cramming’ – maximising the nutrition of each (smaller) mouthful. In response to users eating smaller portions, H&B is looking at developing “nutritionally dense foods,” as is Nestlé, which was the first major food company to launch a new brand explicitly targeted at semaglutide users last year.

Vital Pursuit will include frozen ready meals that are high in protein, a good source of fibre, contain essential nutrients, and are portion-aligned to a weight loss medication user’s appetite.

Therapy and body positivity

There are psychological as well as physical risks around weight loss drugs, explains Cat Chappel, an integrative counsellor and member of the British Association of Counsellors and Psychotherapists (BACP). “One is that there’s a ‘magic drug’ now, so some people think there’s no excuse,” she says. “The other – for those who’ve taken it – is “resentment, a feeling you’ve cheated.” Those who lose a lot of weight on the drugs can experience a loss of identity that accompanies both losing weight and interest in food, the social bonds, and the joy of cooking that food brings. Equally, there are psychological concerns about “developing an identity around a smaller weight, then putting it back on”.

Chappel is concerned about a growing perception of these drugs as quick fixes, which negate the need to address any underlying concerns. “Without therapy, you’ve just removed the coping mechanism. You haven’t addressed what the underlying trauma might be,” she says, likening it to taking off the top of the tree and leaving the roots in the ground. She thinks the idea that people should be able to cure their problems with a jab is “deeply problematic.”

Novo Nordisk, which produces Wegovy and Ozempic, has become one of Europe’s most valuable companies, revealing profits of $17.8bn (£13.8m) earlier this year (Photo: Steve Christo/Corbis/Getty Images)

Novo Nordisk, which produces Wegovy and Ozempic, has become one of Europe’s most valuable companies, revealing profits of $17.8bn (£13.8m) earlier this year (Photo: Steve Christo/Corbis/Getty Images)

She also worries that these drugs might reignite old eating disorders, something that is echoed by Tom Quinn, Director of External Affairs of Beat. Unfortunately, anything which claims to aid weight loss, especially so-called ‘miracle drugs’, are extremely attractive to people with eating disorders, particularly if it’s possible to get hold of them easily, he says. Beat would like to make it mandatory for a thorough mental health assessment to be carried out alongside physical health checks, he adds.

Nutrition

As well as being a BDA-registered dietitian, Linia Patel is a public health researcher whose doctorate focused on health inequality. In her private practice in London, where she works mostly with “corporate, high-performing women,” she has seen “a huge increase” in clients already on semaglutide drugs seeking nutritional support and those seeking advice prior to going on them.

Yet the extent to which semaglutides will shape lives beyond that narrow demographic gives her pause for thought “because most people I see in my practice are getting it privately. At the moment if you can afford it, you can get it,” she continues, “and until everyone can benefit from equal access irrespective of postcode or budget, its success will be limited.” Indeed, the danger is that it creates “even more inequality than we already see in public health because if people are using it to lose 3-4kg before their holiday, they are taking away from somebody with a higher BMI and co-morbidities.”

She is equally concerned about those taking the drug without medical or nutritional supervision. “Weight loss has to be holistic if it is to be healthy and sustainable.” There are also serious risks involved in taking these drugs unsupervised, from deficiencies to complex diseases. “You need to make sure you are having nutrient-rich food to support the weight loss, manage side effects and makes sure you’re losing the right type of weight. Not all weight loss is healthy, and if there is a risk of nutritional deficiency.” These drugs work, says Ms Patel, but “there are many causes of obesity: genetic, psychological, societal as well as a lifestyle – there is never a magic bullet.”

Tailoring

Simon Cundey, the seventh-generation family owner of Henry Poole & Co – one of the oldest tailors on Saville Row – says weight loss drugs have become a big part of their world. Many of his clients are based in the United States, so Cundey had a head start on the trend, with some clients dropping several sizes in the space of a few months.

But there is a limit to how much even one of the world’s finest, most experienced tailors can accommodate such a drastic weight change in a bespoke suit. On trousers, taking in more than four inches brings the pockets too close together; on the jacket, a considerably reduced stomach creates “the floating button look,” he explains, with a bit of cloth hanging around.

“We need to adjust the shoulders and the length of the coat at the front; the angles of the shoulders, shoulder blades and the collar bone. When you lose that mass, the lines of the shoulder change and you really notice the difference.”

Faced with that level of work, many clients just opt for a new suit.