(Credit: Alamy)

Sun 19 October 2025 16:22, UK

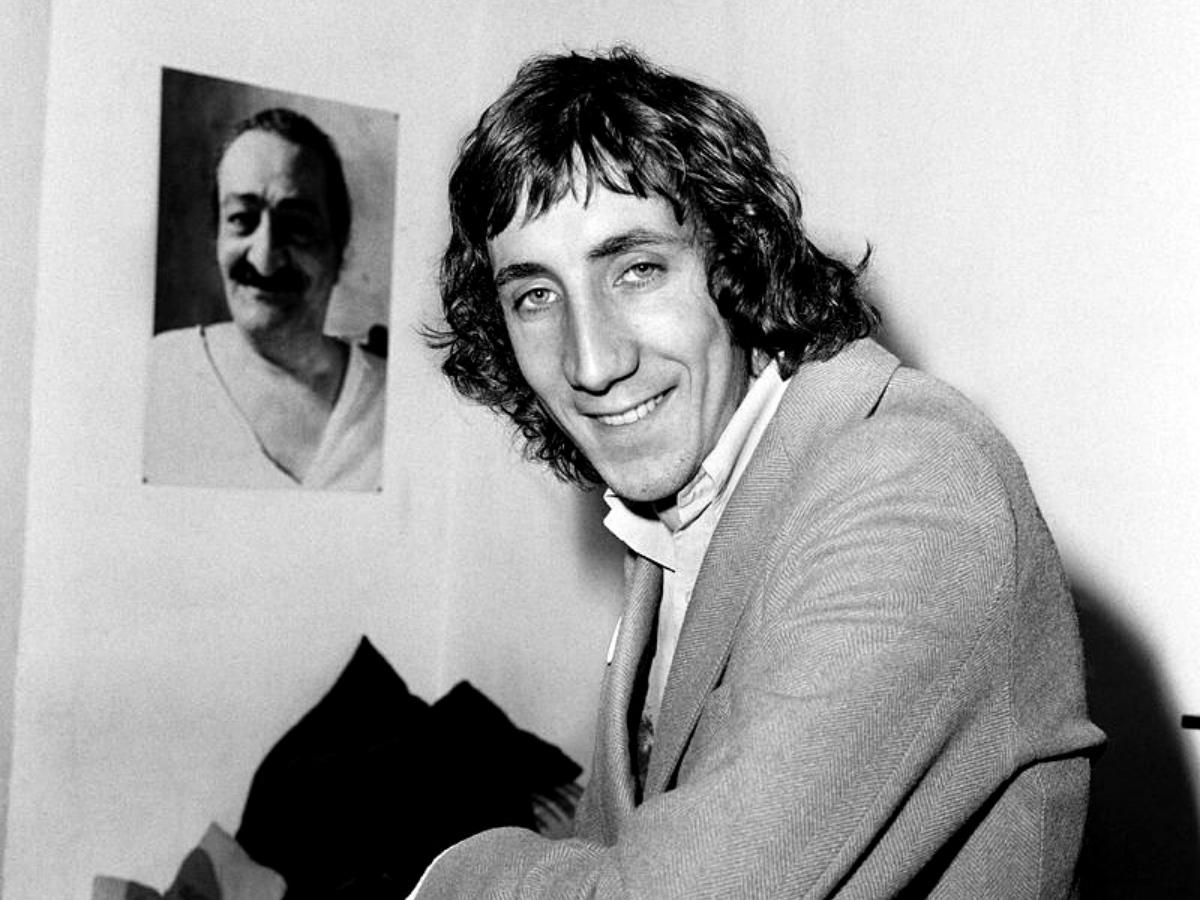

It was Pete Townshend who once said, “Rock ‘n’ roll may not solve your problems, but it does let you dance all over them.” It’s a pithy little quote that outdoes itself. With 17 words, he distilled the history of a cultural movement down to a single sentence. The original pioneers propagated the art form as a way to push through exultant liberation despite the problems surrounding them. Townshend himself has picked up that very mantle.

As the lead guitarist of one of the 1960s most celebrated rock bands, The Who’s Pete Townshend has, unsurprisingly, spent the last 20 years or so desperately trying to correct misconceptions about the era.

As well as claiming that Woodstock really wasn’t all that, he’s refuted claims that Keith Moon was the driving force behind The Who and made numerous attempts to diminish Eric Clapton’s reputation as a world-class guitarist. But even an iconoclast like Townshend has struggled to criticise one of the ’60s most beloved musicians.

The Who were one of the many British rock acts to come out of London’s Marquee Club in the mid-1960s. Townshend was instrumental in their rise to fame, penning the knowingly Kinksesque ‘I Can’t Explain‘ to attract the attention of American music producer Shel Talmy. The track was subsequently picked up by influential pirate station Radio Caroline, ensuring the song reached the ears of Britain’s pop-mad youth.

Just a few years later, The Who were one of the biggest rock bands in the world and found themselves in competition with The Rolling Stones, The Kinks and Jimi Hendrix for control of the London circuit. In a 2021 interview for Guitar magazine, Townsend explained that he’d never understood the obsession with Cream. “It felt to me that sometimes it sounded so empty,” he said of their music.

Jimi Hendrix on stage. (Credits: Far Out / Alamy)

Jimi Hendrix on stage. (Credits: Far Out / Alamy)

Cream seemed to lack bite: “I thought they would’ve been so much better if they had a Hammond player. I always loved Eric’s playing, but not always his sound. It always felt to me like it was a bit muffled, in the Marshall days. That’s why I prefer Traffic and Blind Faith. I like the sound of that.”

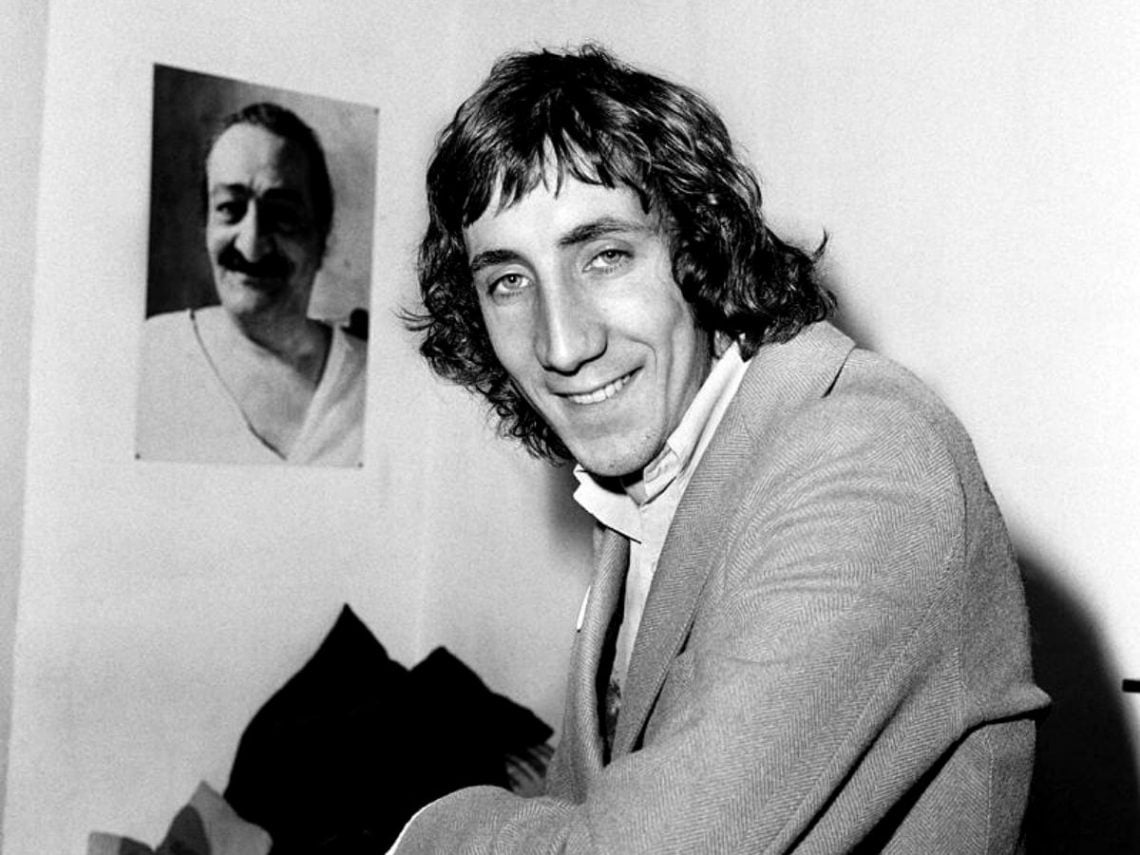

Hendrix, on the other hand, even Townshend couldn’t find fault with. “Although he played single lines, he was such an elegant, remarkable, decorative player as well, and just in a different league,” he said. “I’d like to say I was influenced by him, but who in their right mind would back that up today – even some of the shredders of the modern world – and say they could cover what he does?”

Hendrix might be so singular that he is beyond the level an influence, but aside from his virtuoso playing, his performative style is something that made his skills travel even further. It is this that Townshend most admires. Townshend continued: “And even if you can, you can’t make it speak the way he did, and of course, the other thing, which is not shared often, which is unless you were there, you kind of missed 80 to 90 per cent of where the magic was. He was just such an extraordinary presence once he walked onto the stage with a guitar. It was kind of weird.”

For Townshend, and so many others who witnessed him on stage: “It was almost like he was some kind of angelic, seismic, metaphysical force, who seemed to have light rays coming out of him, and then, as soon as he walked offstage, it would switch off. He was an extraordinary presence. And that definitely made what he did as a player penetrate in a soulful way as well as musically.”

The two guitarists shared a tempestuous relationship, however. As well as engaging one another in a bit of backstage posturing at Woodstock, a scene which encouraged Townshend to tell his band to infamously “leave a wound” on the audience after being shuttled in front of Hendrix on the bill, Townshend also held a degree of jealousy at Hendrix’s performance. “What I did for Jimi – which I always regretted doing for Jimi,” he recalled to Ultimate Classic Rock Radio. “His manager brought him to meet me at a recording studio when he first arrived, and he asked me what equipment to buy. I told him that I’d been using a mixture of an amplifier called Sound City. Which was a Marshall substitute, with a Marshall, to get this really kind of slabby sound.”

“Then, a couple of weeks later, we did a show with him at the Saville Theatre with him allegedly supporting us,” recalled Townshend, “I wish I’d never given him the tip! I was thinking, ‘Oh my God, this guy’s brilliant enough without being a thousand watts loud.’”

Related Topics