In some ways Thatcher, humble of birth but ascending into mock aristocracy, was one of our cleverest leaders. Yet she was, in my humble opinion, corrupted by that great institution Oxford university to become a philistine. That is, someone who never quite, in spite of appearances, rises above a moralising about all things. Oxford, like its sister Cambridge, is full of unique opportunities to ‘get on’; whether that’s to become PM – 21 of the last 29 PMs were Oxford-groomed – or leading lights in the media, acting or the civil service. Stupendous wealth can be assured in some cases, like Sir Tony Blair, from a political life.

But as well as stopping our children’s school milk, closing down our industries and winning the Falklands War, Thatcher regularised the health service so much that managers and clerical staff made it more bureaucratic. And of course, she left the mentally ill to work out their problems on the streets by closing mental institutions, replacing them with the almost invisible ‘care in the community’.

Nottingham next, which when I first went there in 1970, was a vital, hard-working town with factories like the great bike makers Raleigh. In 1960, Saturday Night and Sunday Morning, about a truculent young seducer who worked at the Raleigh factory, showed a new side of working-class England. With the demise of factories and the exportation of work to the Far East, Saturday Night and Sunday Morning is now a wonderful historical document.

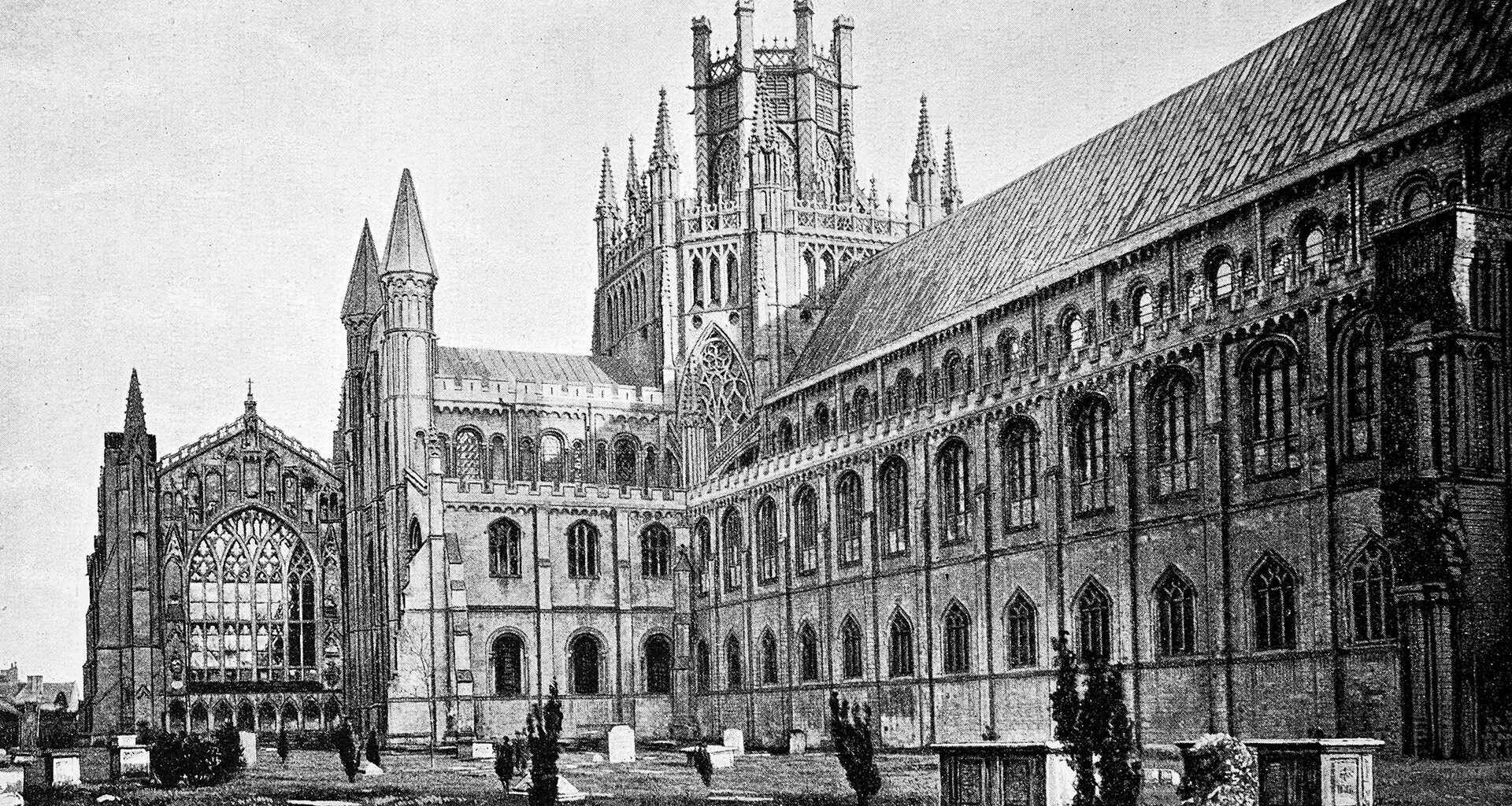

Then to Sheffield, which treated me well when, as a nervous southerner, I came north with my ancient history-studying girlfriend to live in an ex-miner’s cottage as she attended the university. Tess and I later married and she ran our international work when we started Big Issue. Back then, I was nervous because of the things I’d done which required the police to apprehend me. A glistening city with a fine but modest cathedral, Sheffield was a place I loved for the two years we lived there.

The train now passes through the Peak District, through Edale where, as a 16-year-old, I walked in the company of other wrongdoers doing time in a young offenders institute. Brought north to toughen us up, climbing and trekking through what seemed like a permanent winter in midsummer, it gave me a love of rain, damp and mist. Enriched me, as was the intention of the Home Office who had run the youth correctional service not just to warehouse you, but to improve you.

Next, Manchester, where I hitched to aged 18 from London and was picked up by a very drunk driver, which meant I had to take the wheel on a few roundabouts else a crash would have occurred. What a city is Manchester: dynamic and impressive in its Victorian way. Full of grand buildings – and at that time a potential girlfriend, who lived in Burnage where Oasis were later to live.

We started the Big Issue in Manchester the year after we started in London. It seemed the right thing to do. And then Glasgow and Edinburgh soon after.

I love Liverpool and arriving at Lime Street after passing through five hours of history, personal and political, is like arriving at the end of a Shakespeare play (just don’t ask me to explain that).

Social justice awaits. I rush to my venue to wax lyrical on why we need to end the tyranny of ‘the inheritance of poverty’.

Do you have a story to tell or opinions to share about this? Get in touch and tell us more.

Reader-funded since 1991 – Big Issue brings you trustworthy journalism that drives real change.

Every day, our journalists dig deeper, speaking up for those society overlooks.

Could you help us keep doing this vital work? Support our journalism from £5 a month.