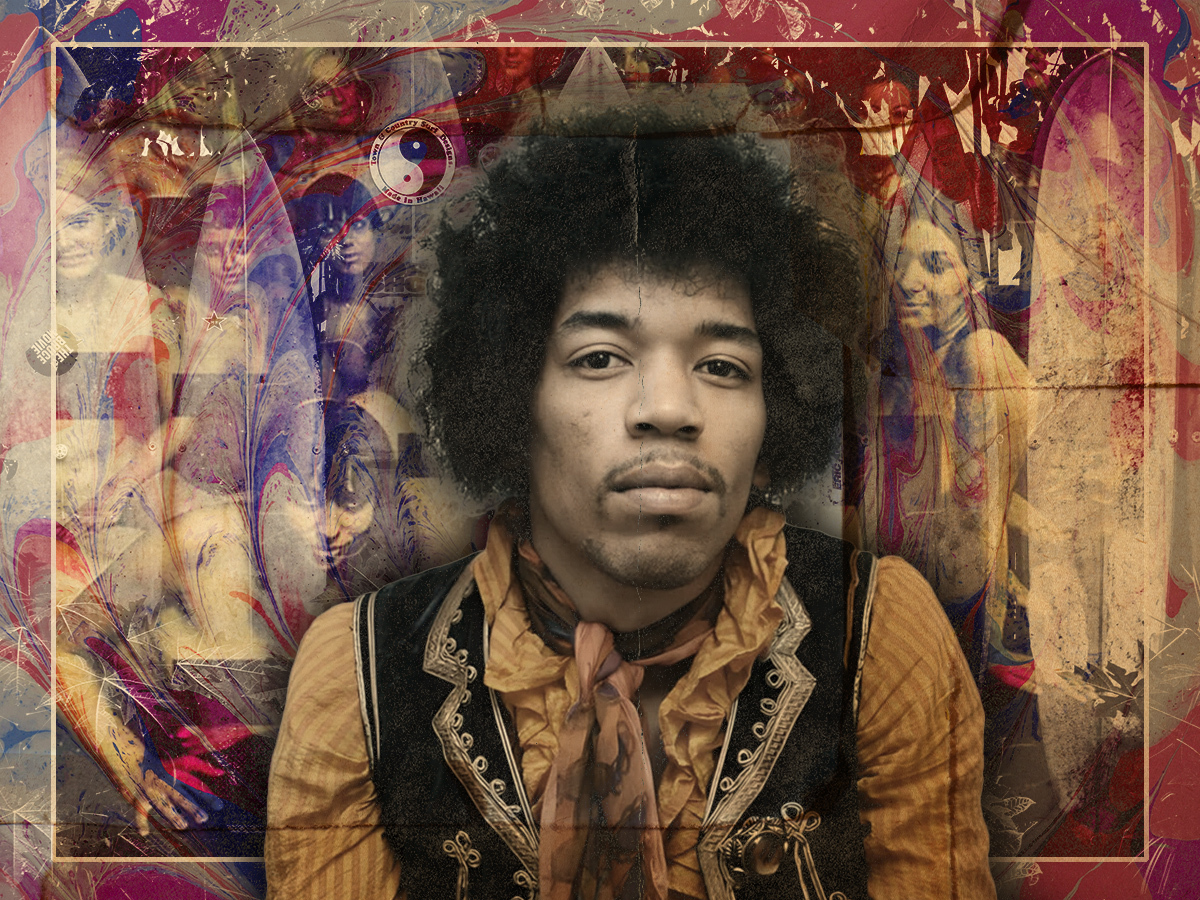

(Credits: Far Out / Bent Rej / Reprise Records)

Sat 25 October 2025 20:45, UK

The subjectivity of art is a curious thing. We might think talent is self-evident even in the mystic realm of creativity but it is still subject to manipulation. Jimi Hendrix stands as strange evidence for this phenomenon.

He is the greatest guitarist in history, which now feels foregone. But for a while, he skirted perilously close to the ash heap of history without ever making his mark. He had to hustle for session work endlessly, often facing rejection, and it took almost seven years before Chas Chandler recognised his class and signed him up.

You might think that you could proceed with a classic ‘the rest is history’ quip from this point, but it wasn’t. Even after Chandler signed him, Hendrix found himself busking on the streets in the outskirts of Newcastle, where bemused miners wondered why there was a virtuoso in strange clothes standing outside a Greggs.

Even when he released his debut single, ‘Hey Joe’, things hardly got off to a flier. He peaked at 105th in the US. While he was starting to make waves among his fellow musicians, blowing the likes of Eric Clapton off the stage at an impromptu gig in London and gilding enough esteem from those on the scene to ensure his next single, ‘Purple Haze’, rose to third in the UK, he still hadn’t quite convinced the world.

That became readily apparent when he performed in France with the Pretty Things. The group were renowned for putting on a stunning live experience, later evidenced by the fact that they were among the few daring enough to go on tour with Led Zeppelin. They had a carefree punky spirit before punk had even been thought of, and rattled through a lifetime’s worth of shows in such succession that they had honed their act to the point that Dick Taylor reflected, “We would have found it hard to do a really bad gig.”

One night in France, they were in fine form, and Hendrix, fresh to the fore of popular music, was concerned about following them in his typically humble way. Everything was fresh for the future icon, even the venue, and nerves were apparent. “Jimi had never been to France, and the whole Hendrix experience was very new,” the Pretty Things’ singer Phil May told Peter Makowski.

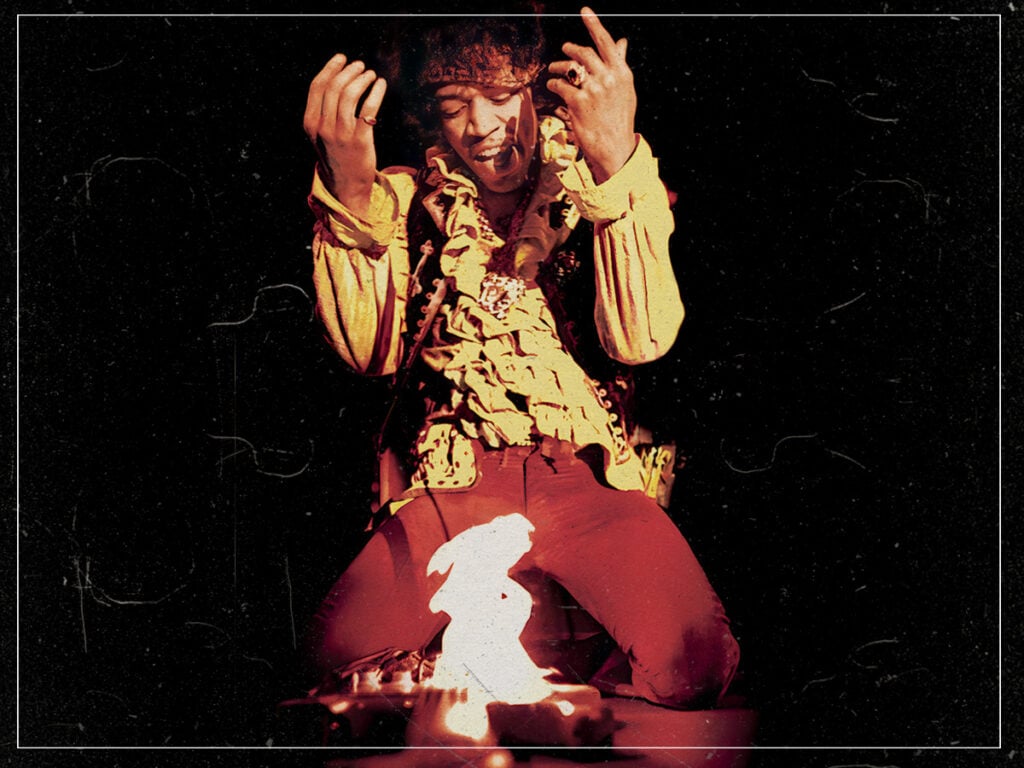

Jimi Hendrix’s famous guitar-burning ceremony. (Credits: Far Out / Sony Music Entertainment)

Jimi Hendrix’s famous guitar-burning ceremony. (Credits: Far Out / Sony Music Entertainment)

Still, the Seattleite was in good humour. “I sort of wound him up about how much the French would fall on their knees in reverential disbelief when they saw him,” May recalls. “We went on first and there were about 6,000 people there. Poor old Jimi went on, and after about two numbers he cleared the place [laughs].”

After the riotous reception of the Pretties, the greatest guitarist in history somehow flopped. You now wonder, do those in the crowd retell the story and claim they witnessed greatness, or do they shrug and say that the king wasn’t all he was cracked up to be? Either way, May concludes, “I don’t think he ever trusted me again.”

Adding, “Of course, a couple of months later he went down a storm. But that’s the French: they need to be told when something is hip.”

That’s not just true of the French, but a psychological quirk of humanity. Context and expectation always frame our experience. Take, for instance, the Joshua Bell experiment from 2007. The world famous violinist is regarded as one of the greatest instrumentalists in history. But before a show where tickets went for huge fees, he played a $3.5million dollar Stradivarius in a subway station and the only major attention he received from bypassers was from children.

As the psychologist Ellen Langer said, “Perception is not passive reception but active construction.” Thus, the Pretty Things went down such a storm as a revered live act that basically anything unknown that followed was always up against it. Psyches had been primed in all the wrong ways. Like savoury after sweet, he simply wasn’t to their taste that night.

I recently chatted about this very phenomenon with Nick Seaver, the music algorithm expert behind the book Computing Taste, and he explained, “In any context where we have taste, we have taste in a world with other people in it.”

He suggests, “No matter what, we’re always learning about music from outside of ourselves. The music is made by other people. Then, we decide what kind of person we want to be in a world full of other people. There’s a lot of sociology work about how taste maps to social status. I don’t think it makes sense to think of taste as something that is uniquely our own.”

So, was it the Pretty Things being brilliant, Hendrix being nervy and naff that night, or the hippest member of the crowd deciding they’d had their fill and everyone following? Regardless of the oddities, for at least one night, the Pretties were too hot for Hendrix to handle.

Related Topics