The sun was low and this Canada lynx moved through the shadows as he approached the shore of a frozen lake in southern Yukon. Its cousin, the Eurasian lynx, vanished from Great Britain about 1,300 years ago. The debate over including lynx in a UK rewilding effort is under debate. Credit: Keith Williams / CC

The sun was low and this Canada lynx moved through the shadows as he approached the shore of a frozen lake in southern Yukon. Its cousin, the Eurasian lynx, vanished from Great Britain about 1,300 years ago. The debate over including lynx in a UK rewilding effort is under debate. Credit: Keith Williams / CC

EDITOR’S NOTE: One remarkable component of the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem is its complete suite of wild North American mammals living much as they did before European explorers arrived. In fact, no other place in the Lower 48 has such a collection of predators and plant-eaters; from lynx to grizzly bears and from beavers to bison.

That puts an onus on us as guardians of such a rare landscape to both maintain its qualities and share its lessons. This series of stories wrestles with how we define the word “wild,” in a place tangled with prehistoric food webs and artificial boundary lines.

So what can a Yellowstone grizzly bear teach a Eurasian lynx? Do Polish free-roaming bison have advice for their American cousins? And can a world-class wild trout fishery double as a world-class business? Is rewilding really wild?

In this Mountain Journal Sunday Read, here’s Part 1 of our series, “What Is Wild?”

—–

What can a Yellowstone grizzly bear teach a Eurasian lynx?

In a pretend world of talking animals, the two keystone predators might compare notes on the windswept comforts of the Lamar and Loch Ness valleys. They might weigh the risks of raiding chicken coops. They might have a tense conversation about how to deal with the biggest predator of all: Us.

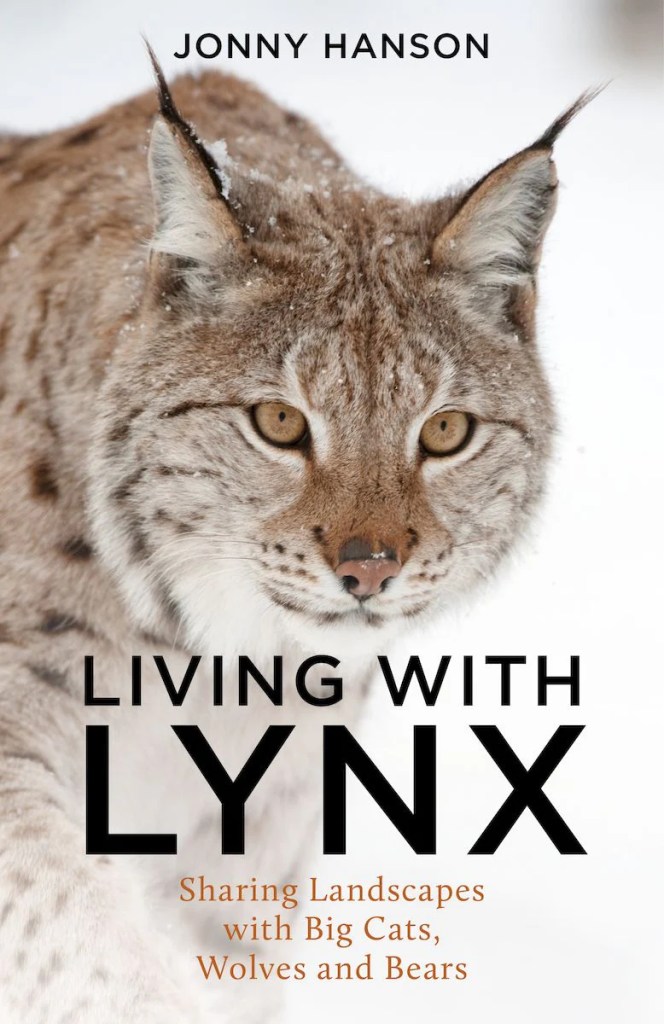

In the real world of rewilding, Irish science author Jonny Hanson explored Greater Yellowstone’s Tom Miner Basin seeking insight for how those charismatic megafauna coexist with people. It was one stop in a globe-circling quest with observations of lions in Malawi, snow leopards in Nepal and wolves in Switzerland. His new book, Living with Lynx: Sharing Landscapes with Big Cats, Wolves and Bears, starts with the question of returning apex predators like lynx to the British Isles.

That green and pleasant land has filled the English-speaking imagination with animal teachers, from Winnie-the-Pooh to Aslan the Lion. Hanson counters that, in reality, the United Kingdom is one of the most nature-depleted places in the world. Aside from the red deer and roe deer confined to private game farms, virtually no wild land mammals bigger than a badger inhabit Great Britain. In describing that oddly empty landscape, Hanson draws equally on his background as an environmental social scientist at Queen’s University Belfast and as a small-plot farmer battling to keep foxes from killing his geese.

“I wanted to help British farmers to understand this topic, understand the pros and cons, and make up their own mind about it,” Hanson told Mountain Journal. “Sharing landscapes with these species is as much about sharing landscapes with each other.”

In spring 2024, grizzly bear 1063 emerged from her den in Grand Teton National Park with three cubs. At 7 years old, she was considered relatively old for having her first litter. The following year, two of her yearlings were killed by an adult male grizzly. Grizllies currently remain on the U.S. endangered species list. Credit: Ben Bluhm

In spring 2024, grizzly bear 1063 emerged from her den in Grand Teton National Park with three cubs. At 7 years old, she was considered relatively old for having her first litter. The following year, two of her yearlings were killed by an adult male grizzly. Grizllies currently remain on the U.S. endangered species list. Credit: Ben Bluhm

His research across the Rocky Mountains, from Missoula, Montana, to Fort Collins, Colorado, sought examples of ecotourism and range-riding cattle protection. Those activities, focused on large predators like wolves and grizzlies, need some translation when applied to the much smaller European felines.

Averaging around 40 pounds, the Eurasian lynx is somewhat larger than its North American cousin, the Canada lynx. That’s still a long drop in comparison to a 400-pound grizzly bear. The cat and bear, however, occupy similar links at the top of their respective continental food chains. Both are listed as threatened species under the U.S. Endangered Species Act and similar European laws. And both inspire equal unease in the minds of many humans worried about the threat to domestic livestock and possibly themselves.

One big difference is that today’s grizzly bears in the Rocky Mountain West have occupied their space since prehistoric times. Although their populations dipped so low in the 1970s that they became the eighth mammal to win protection under the U.S. Endangered Species Act, they never disappeared. Neither had the Canada lynx in the United States, although it wasn’t until 2000 that it made the endangered species list and its recovery plan was only finalized in 2024.

Eurasian lynx did vanish from Great Britain about 1,300 years ago, making their return a rewilding project rather than a recovery effort. Or, as Hanson puts it in his book, “moving lynx to Ireland is not a reintroduction but a novel translocation, and therefore the creation of an entirely new ecosystem rather than the recreation of a previous one.”

“Rewilding in today’s world doesn’t mean having as many predators in as many places as we can. It means let’s restore relationships with these animals and the natural world.”

Cristina Eisenberg, conservation biologist

Hanson’s book was just going to print when news broke in January that “guerrilla rewilders” had released four Eurasian lynx in Scotland’s Cairngorms National Park. All four felines were quickly trapped. While lynx reintroduction has subsequently stalled in Scotland, the incident did stir up memories of a more accepted rewilding effort: the unsanctioned “beaver bombing” on the River Tay that resulted in the largest free-roaming beaver population in the United Kingdom.

Rewilding critic and King’s College London geographer Toryn Whitehead offered three reasons why the lynx reintroduction was a bad idea, none of which was biological. Writing in the U.S. National Library of Medicine, Whitehead argued that kind of ecological manipulation 1) caused a breakdown of trust and dialog, 2) stalled efforts at encouraging coexistence between farmers and lynx, and 3) led to the spread of misinformation and politicization.

Hanson said all those results were playing out now.

“The Scottish prime minister put a red pen through any other reintroduction plans,” Hanson said. “And the tug and pull of conservative versus liberal approaches to managing large carnivores became a cynical exploitation of these animals for political capital. So even though there’s a strong ecological case [for returning lynx], the weakest part is that political aspect. If anyone can find mileage politicizing the return of lynx to Britain, they will do so.”

Irish author and social scientist Jonny Hanson. Credit: Jaden Dales

Irish author and social scientist Jonny Hanson. Credit: Jaden Dales

Other cases have played out differently. Christopher Preston, environmental philosopher and professor at the University of Montana, cataloged several in his 2023 book, Tenacious Beasts: Wildlife Recoveries that Change How We Think About Animals. Preston trekked into the Bitterroot Range along the Montana-Idaho border to observe Pacific salmon return to spawning streams unreachable for almost a century. He visited a forest in Kent, England where the European version of bison is being reintroduced. In Italy, he tracked Marsican bears, which are related to North America’s grizzlies. In each place, he observed the challenges people erect against sharing space with predators.

“Europe is a culture obsessed with civilization,” Preston told Hanson during the Irishman’s Montana visit. “And it fitted well to banish these animals from our human geographies. In other words, the wild is out there, not over here.”

Wolves left a particular impression on Preston. European folklore provided much of childhood’s wolf imagery, from Little Red Riding Hood to The Three Little Pigs to Peter and the Wolf. And yet, continental Europe has seen a natural resurgence of wolves from the Netherlands to Romania.

“Even densely populated countries like Belgium have wolves,” Preston told Mountain Journal. “The central government has generally taken a pro-predator position. They give you money to fence pastures and compensate losses, but the directive from on high is clear. There are 650 million people in Europe living in cities, and they want to have a wilder landscape.”

That presents considerably different coexistence problems for Europeans, compared to Americans. For example, a growing population of wild beavers in the Netherlands burrow into protective dikes, raising the risk of catastrophic floods in a place where a quarter of the land is below sea level. Because Dutch law mostly prohibits killing wild beavers, the country has had to spend millions of Euros making dikes beaver-resistant.

Hanson delivers his 2023 TEDxTalk, discussing his experience with grizzly bears in Montana and ways to coexist with carnivores again. Click on the image above to watch the talk.

Hanson delivers his 2023 TEDxTalk, discussing his experience with grizzly bears in Montana and ways to coexist with carnivores again. Click on the image above to watch the talk.

Preston added that he didn’t hear any calls for creating a Yellowstone Park-style refuge in the middle of the European Union. And the discussion of “rewilding” there had a distinct framework.

“They have to still be very careful to say rewilding involves people,” Preston said. “They put the economic argument very high: Rewild the landscape and provide jobs for people and let people still live on the landscape.”

That economic angle was a major factor for Montana filmmaker Tom Opre. His latest project is Real Yellowstone, a documentary about the challenges sharing a rural landscape between domestic livestock and wildlife. But his 2024 effort was The Last Keeper, which explored the culture of hunting preserves and rewilding efforts in Scotland.

In that film he looked at conflicts between commercial game keepers who’ve managed habitats to support trophy red deer, grouse and salmon for hundreds of years, and conservation organizations pushing for a more biodiverse but economically divisive kind of ecosystem management.

“There’s different types of rewilding, and what’s going on in Scotland is not similar to what you’re seeing with American Prairie,” Opre said, referring to the Montana-based organization working to restore wild buffalo to the Missouri Breaks area. “In Scotland, there’s a group of urban people that don’t have connection with land, but they have historical grievances. They don’t like landowners, who are perceived to be the bad people.”

Many of those Scottish landowners, and the gamekeepers who work for them, intensively maintain Highland landscapes for hunting and fishing. They do it with traditional methods hundreds of years old. That results in habitat favoring grouse, sheep, cattle and red deer, an ungulate bigger than an American mule deer yet smaller than an elk. But it comes at the expense of predators, from the bears, lynx and wolves that were eliminated from Great Britain hundreds or thousands of years ago, to the weasels, stoats and foxes that are actively removed today.

“You had this Victorian age of sporting estates, where they managed the land for the utilization of wildlife,” Opre said. “You burn off the older heather, which gets young growth that helps with the population of grouse, because the landowner wanted to shoot a bunch of grouse. But now if you stop managing for grouse, within 10 years you’ll lose 50 percent of the biodiversity in Scotland.”

Some British conservation groups counter that local economies could benefit far more from tourists coming to watch wildlife than hunters coming to hunt it. Hanson examined how that has worked in many parts of the world, from guided grizzly viewing sites along the Yellowstone National Park border to snow leopard excursions around Mount Everest.

“I wanted to help British farmers to understand this topic, understand the pros and cons, and make up their own mind about it. Sharing landscapes with these species is as much about sharing landscapes with each other.”

Jonny Hanson, author, social scientist

One pattern he saw repeated was the different ways people reacted to familiar and unfamiliar animals. In Nepal, Hanson found livestock herders were often comfortable with snow leopards, which routinely prey on their sheep and yaks. But they were resistant to the idea of reintroducing wolves to their mountainsides, even though wolves were once a native predator in the area before they were extirpated. That held true even when Nepalis considered the idea of attracting more wildlife-watching tourists, who would have an easier time spotting wolves than the extremely elusive leopards.

Lynx aren’t much easier to see, either in North America or Europe. Nevertheless, their potential reintroduction in Great Britain is promoted as an ecotourism asset. One of the biggest rewilding efforts in Scotland is taking place on the Alladale Wilderness Reserve. Montana-based conservation biologist Cristina Eisenberg was a lead scientist in a project returning trees to 30,000 acres with the goal of also returning lynx and possibly wolves. She told Mountain Journal the idea faced steep challenges.

“Rewilding in today’s world doesn’t mean having as many predators in as many places as we can,” Eisenberg said. “It means let’s restore relationships with these animals and the natural world. You can’t just say ‘Let’s restore large carnivores by putting them in protected areas.’ It hasn’t worked well with lynx.”

In a long career documenting Indigenous knowledge in people’s relationship with the environment, Eisenberg was among the first to research the trophic cascade effects of wolves returning to Greater Yellowstone. A theme in both her books, The Wolf’s Tooth and The Carnivore Way, was coexistence with predators.

Eisenberg earned her doctorate studying the transformation of Yellowstone National Park’s forests and meadows after the reintroduction of wolves in the 1990s. She helped bring the complex concept of trophic cascades to everyday conversation, such as how the presence of wolves and bears triggers changes in the way deer and elk graze, which changes the way grass and trees grow, which opens opportunities for birds and other animals to thrive.

A yearling member of the Wapiti Lake Pack inspects the photographer’s camera in Yellowstone National Park, October 2025. The 1995 wolf reintroduction to Yellowstone is considered among the world’s most successful conservation efforts. Credit: Ben Bluhm

A yearling member of the Wapiti Lake Pack inspects the photographer’s camera in Yellowstone National Park, October 2025. The 1995 wolf reintroduction to Yellowstone is considered among the world’s most successful conservation efforts. Credit: Ben Bluhm

In another example, her observations of Kintla Pack wolves in northwest Glacier National Park found significant wolf and elk activity in two separate sites: One had a dense forest that hadn’t been burned since 1870; the other had experienced a major wildfire in the early 2000s. The static forest area had little complexity. The burned-over meadows showed a strong trophic cascade of varied plant growth and bird activity.

“Wolves are considered our main teacher for most Indigenous people in North America,” Eisenberg said. “They’re keystone in the knowledge and wisdom they hold. If that is the path to get people’s attention so they think about the natural world a little differently, I think that is a good thing.”

But she cautioned the process is not as simple as adding wolves or lynx to a landscape. In her analysis of wolf impacts in both Yellowstone and Glacier, Eisenberg identified a range of factors that had to be in place for a trophic cascade to get moving. For example, when she first moved to a heavily wooded property in Montana’s Swan Valley, she started applying Native American forest-thinning practices. Abrupt changes occurred.

“Within about three weeks, we had snowshoe hare,” she recalled. “Two months after that, the lynx came back. I’d never seen lynx on the land. They need that complex forest structure of early seral forests plus old trees for cover. Then they use all that habitat. The animals celebrated by coming back.”

Eisenberg deliberately chose the word “celebrated” to contrast with what she called “command-and-control Western science.” Even in the conservation community, she said, the attitude tends to be that humans are superior to other life forms and don’t want to share the place as equals.

“Each spot is unique,” Eisenberg said. “The relationship between animals, the trees, the understory, fire and prey will be different because of different things going on.”

Related