There are nights in Manchester when the rain feels like it’s never going to stop.

When the gutters groan, the drains choke, and the Medlock swells with a deep, guttural sound, a sound that’s older than the city itself. To get you in the mood for Halloween, we’ve got a spooky story for you.

Most people hurry past it. They cross the bridges at Mayfield or Ardwick, throw a glance over the railings, and see only a sluggish stream curling through stone. But on a night in the summer of 1872, that modest river turned monstrous, and what it brought with it was something the people of Manchester would never forget. Changing the Halloween history of Manchester forever.

A flood to end all floods in Manchester

The River Medlock

The River Medlock

That July, the skies broke open. For two whole days, the rain poured down as if the heavens had cracked. It’s believed that a month’s worth of rain had fallen in 48 hours. The Manchester Courier described it as “a water spout had burst over the city.”

Streets became canals. Cellars filled in minutes. And the River Medlock, that narrow, twisting vein running from Oldham through Clayton, Bradford and Ardwick to Castlefield, swelled to the very limits of its banks. One person was killed, and there were landslides near Clayton Railway Station.

On the morning of Saturday, 13th July, the river tore itself free.

Philips Park Cemetery today

Philips Park Cemetery today

At first, it was a trickle through the grass in Philips Park. Then the torrent came, smashing through the footbridge near Bradford, hurling it aside as though it were no more than a toy.

The surge ripped through the low-lying Roman Catholic section of Philips Park Cemetery, back then known as Bradford Cemetery, where twelve thousand poor souls had been buried in just six years.

The ground heaved. Graves split. Coffins lifted from the earth like driftwood. The Manchester Courier described it with terrible poetry:

“Still on the mighty water came, where lay the silent dead.

And soon, alas! The coffins were uplifted from their bed.”

What followed was Manchester’s most macabre flood, the night the Medlock carried its dead into the city.

Where were Manchester’s poor buried?

Angel Meadows was a famous grave burial site

Angel Meadows was a famous grave burial site

The Roman Catholic plots were the lowest and poorest ground in the cemetery, a place where paupers, Irish labourers, and the city’s forgotten were laid to rest. When the Medlock burst its banks, it swept straight through them.

Witnesses spoke of tombstones bobbing like boats. The ground dissolved into a thick, grey soup. And then, one by one, the coffins came free.

By early afternoon, the first bodies were seen floating past Clayton Vale. The Printworks at Clayton Vale’s machinery was swept away, and a footbridge at Bradford was destroyed, with homes submerged near Fairfield Street. By dusk, the bodies had reached Ancoats Bridge.

The River Medlock

The River Medlock

Others saw limbs tangled in branches, or coffins wedged beneath bridges. In Ardwick, factory workers fished out a body that had been carried two miles from its grave. And in Mayfield, where the Medlock curls past the old depot, now a hub for food, music, and nightlife, the river poured into cellars, carrying with it the remnants of the cemetery.

Some of the corpses were newly dead, their coffins fresh and sealed. Others had been buried for years, their remains half-skeletal, wrapped in fragments of linen. The smell was overpowering. The horror, unimaginable.

Fairfield Police Station

Fairfield Police Station

The police were called, and Fairfield Street Police Station was turned into a temporary mortuary. Over the next three days, officers and volunteers dragged the Medlock, hauling the bodies onto the banks and laying them side by side.

The station filled with the drowned and the dead, the forgotten poor of Bradford, returned to the living in grotesque procession.

Men worked with lanterns late into the night, the river’s surface glinting red in the light. Onlookers gathered on bridges, holding handkerchiefs to their faces. The Courier reported “ghastly forms of old and new, lying open to our view.”

By the time the waters subsided, seventy-six bodies had been recovered, though rumours claimed the number was far higher. Some said hundreds were lost, carried through the Irwell and out to sea. Others whispered that the Medlock had reclaimed them, drawing them down into the dark culverts beneath the city.

“one of the most appalling spectacles ever witnessed in this city.”

Most appalling spectacles ever witnessed

Manchester was horrified. Newspapers printed grim illustrations of the washed-out graves. The Manchester Guardian described the scene as “one of the most appalling spectacles ever witnessed in this city.”

Anger spread quickly, especially among the city’s Catholic community. They had long complained that their section of the cemetery had been placed on the worst ground, low-lying, damp, and neglected. Now they had proof.

Letters poured into the press. A Catholic priest wrote to the Home Secretary himself, demanding an inquiry into what he called “a disgrace to Christian decency.”

The priest argued that the Corporation had shown contempt for Manchester’s Irish and Catholic dead, burying them on cheap, flood-prone land while the higher, drier plots were reserved for wealthier Protestants.

His words struck a chord.

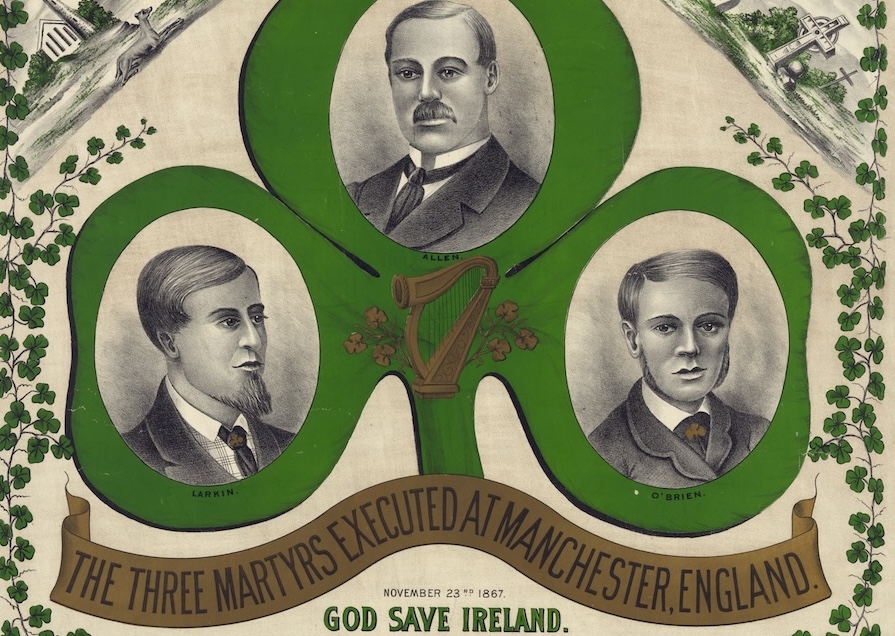

The Manchester Martyrs

The Manchester Martyrs

At the time, anti-Irish sentiment ran deep. The memory of the Manchester Martyrs, three Irish nationalists hanged at the New Bailey Gaol just five years earlier, still haunted the city. The Irish working classes, who had built the railways and mills, were often demonised in the press as unruly, dangerous, or disloyal.

And now, their dead had been cast into the river.

The government ordered an inquiry within a fortnight. But the meeting, held in the dissenters’ chapel at Philips Park, quickly descended into chaos.

“We want to be treated as Christians, not as barbarians!”

Witnesses shouted across the floor. Angry residents demanded to know why the graves had been placed so low. One man cried, “We want to be treated as Christians, not as barbarians!” The crowd surged, the police were called, and the meeting had to be suspended.

Eventually, the Town Clerk announced that seventy-six bodies had been recovered and reinterred – though few believed him. The Catholic clergy insisted the true number was much higher, and that many of the remains were never found.

The Great Flood Ballad

The horror inspired a broadside ballad: a popular folk song printed on single sheets and sold in the markets of Ancoats and Shudehill. It became known as The Great Flood Ballad, and it captured the morbid fascination of the time:

“Still on the mighty water came,

Where lay the silent dead.

And soon, alas! the coffins were

Uplifted from their bed.

And ghastly forms were now beheld,

Hurrying quickly by;

Brave men were awestruck at the sight,

And women raised a cry.”

The song spread across Lancashire and beyond, sung in pubs, on street corners, and even in music halls. Each verse painted the image of bodies drifting through Manchester’s industrial heart, past the mills and the arches, through streets still slick with rain.

In the decades since, it has been revived and recorded, most recently by Manchester reggae-folk band Edward II, a strange and fitting echo of history through sound.

The flood exposed the city’s vulnerability. Not just to rain, but to the decisions made by those in power. In the aftermath, Manchester’s engineers set about “canalising” the Medlock, straightening and narrowing its course, walling it in with stone to prevent future flooding.

The Red River

But the solution brought its own curse. The vegetation was stripped away, the water sped up, and in heavy rain the river still surged dangerously. Locals began calling it The Red River, for the iron-rich silt, and perhaps for what it had once carried.

Out of the disaster, though, came something lasting. The Catholic community vowed never again to bury their dead on neglected ground.

By 1875, a new cemetery had been consecrated in Moston, St Joseph’s, built on higher land and designed as a dignified resting place for Manchester’s Catholic dead. At its centre, they erected a monument to the Manchester Martyrs.

Today, St Joseph’s remains one of the city’s most peaceful places. Yet walk its paths on a stormy night, and you might still feel the weight of that old injustice in the air.

Walk along the Medlock now, through Mayfield Park, past the arches, under Oxford Road and Deansgate, and it’s hard to imagine what it once was. The water is low and dark, hemmed in by stone, winding quietly beneath the city’s feet. But in the 19th century, the river was open, alive, and dangerous. It powered mills and flooded cellars, carried waste and industry, and once, it carried the dead.

When the park developers first unveiled their plans for Mayfield’s new riverside green space, one local historian joked that they should commemorate the flood with a children’s “coffin race” every July, “tiny caskets floating down the Medlock in honour of the 1872 dead.”

The developers didn’t take him up on it. But the story lingers. Next time the rain lashes down and the Medlock begins to rise, remember this: beneath those murky waters lie stories that will never quite stay buried.