A talk by Professor Richard Rodger at Edinburgh Central Library provided an informative and engaging overview of the history of The Cockburn Association.

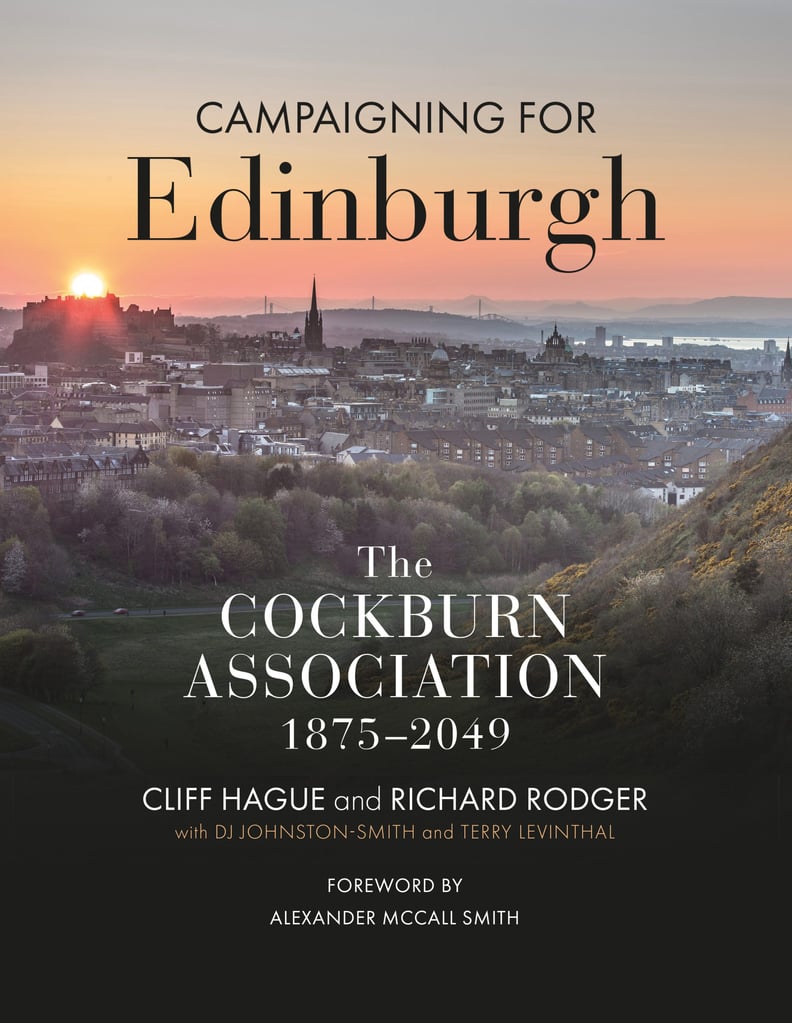

The event coincided with the publication of the new history of Scotland’s oldest conservation charity, Campaigning for Edinburgh, which Rodger has co-authored.

Rodger, Emeritus Professor of Economic and Social History at Edinburgh University, has published widely on Edinburgh, including The Transformation of Edinburgh, and Happy Homes: Cooperation, Community and the Edinburgh Colonies

Rodger offered an insightful look into the history of Edinburgh’s pioneering civic watchdog, exploring the Association’s origins, its central role in managing the city’s development and preservation, and the enduring relevance of its work today. Rodger considers the Cockburn to be “a very important organisation in the city.” He offered “my assessment of it,” rather than “the gospel,” and felt free to criticise the Association’s past errors and its fallow, ineffective periods.

Historical Context and Lord Cockburn

Governance Before Modern Edinburgh

Rodger emphasised the profound difference in how Edinburgh was governed before 1856, the start of the modern unified city overseen by the council. Prior to this, the council was less significant; the Deans of Guilds and the Police Commission “really ran the city till 1856.” Lord Cockburn was a significant figure in these influential bodies. Significantly, Cockburn was a pioneering figure in the world of conservation.

The talk presented a nuanced view of Lord Cockburn, lawyer, judge and literary figure, as well as a prominent Whig and reformer. Cockburn’s promotion of architectural conservation (for instance his role in the preservation of John Knox’s House) inspired the Association’s founding in 1875. Rodger related how Cockburn’s travels across Scotland, as part of his role as a judge, made him aware of the varied architecture of the country. Cockburn was critical of aspects of the city, considering the New Town only beneficial to “polite society”.

He notably opposed the transition of Princes Street from residential to commercial use. Rodger noted that once established as a primarily retail centre, “there was no turning back.” The contemporary relevance of this is clear. The widespread dismay over the street’s perceived decline may be seen as just another such evolution in the future. Organisations like the Cockburn are crucial for bringing this historical perspective to debates, helping to raise the level of discourse on such matters.

Scope, Image, and Purpose of the Association

Challenging the “New Townie” Image

Through archival research, Rodger addressed the perception of the Cockburn Association as a body of the ‘great and the good’, overwhelmingly dominated by those in the West End and New Town – essentially a “New Townie sort of thing.” While this perception has “dogged the association,” Rodger found it a little bit unfair, given the diversity of its activities, including many interventions well beyond the city’s historic centre.

Preservation, Green Spaces, and a Positive View

Rodger was keen to outlined that Association’s focus has always included green spaces, demonstrating it wasn’t “just protecting old houses.” It was a leader in the preservation movement from the 1880s, fuelled by nostalgia for the Old Town (seen in the 1886 International Exhibition). This shows that the current fascination with Edinburgh’s past and Lost Edinburgh is nothing new.

The Association also led early campaigns against the over-commercialisation of the city, such as a large billboard advertising Bovril that covered part of Calton Hill, next to Waverley. In many cases, this would be visitors’ first view of the city. This, they argued, was not “in keeping” with such a historic spot. Such interventions have continued, with the Association keen to highlight and push back against attempts to commercialise the public domain, including attempts to ‘privatise’ green spaces and parks. This has included opposition to blackboards erected to prevent the public seeing ticketed concerts in Princes Street Gardens.

Crucially, Rodger stressed that the Cockburn has always held a positive view of the city’s potential. He quoted a document from the Victorian era stating that the Old Town “is not a slum” but just “shamefully neglected”. In short, making it clear that an area or building’s current state says little about its potential; a point illustrated by the resurgence of Leith since the mid-Eighties. Rodger concluded that the Association had a positive vision for the city, believing that with the right sort of effort, backed up by expertise, neglected areas and buildings could find new life. While Rodger believes that, at its core it has an optimistic vision of the city’s future, distinct from the prominent ‘declinist’ views of the city, according to which Edinburgh is in terminal decline. This is not the Cockburn Association’s view.

The Watchdog for the Civic Realm

Successful Resistance and the Watchdog Role

Rodger asserted the Cockburn Association was correct to critique and oppose schemes like the inner-city ring road, which it considered “unsettling” to the city’s coherence. In this, it performed its duty as “a watchdog for the Civic realm.” Such episodes of resistance were effective partly because Edinburgh’s civic society was stronger than Glasgow’s in that era, as noted by Professor David McCrone in the Q&A. Here we have echoes of Alan Taylor’s view that Edinburgh’s middle class have been consistently effective at saying no to large scale projects, of which the ring road is the most notorious.

Rodger believed the Association should maintain its watchdog role while also supporting innovative, positive schemes. It needed to have a vision for the city. He urged action against the homogenisation of the city to maintain its unique character and the need for greater diversity within areas, a sphere where he felt the city had “not been very successful.” The city remained marked by wide social divides.

Limits and Enduring Voice

The talk concluded by acknowledging the Association’s limitations. It is, ultimately, “an underfunded voluntary organization” with limited influence and fluctuating success. However, Rodger described the Cockburn Association as an institution with “a voice, a small silent voice in comparison to the wider forces affecting the city.” The challenge is to use that voice effectively, focusing on everyday issues like the streetscape, as well as major challenges like over-tourism.

Rodger’s talk illuminates the Cockburn Association’s enduring role as Edinburgh’s civic watchdog. The central themes were its foundation which drew on the progressive thinking of Lord Cockburn, its consistent, positive vision for the city’s improvement (even when areas are “shamefully neglected”), and its function as a critical counter-balance to forces of over-development and commercialisation. Rodger’s nuanced assessment shows an organisation that has evolved beyond a narrow “New Townie” focus to campaign for green spaces and the overall character of the city. While acknowledging its limitations as an “underfunded voluntary organization,” the report underscores the Association’s vital, continuous effort to maintain Edinburgh’s unique heritage and coherence against the powerful forces of change, ensuring its “small silent voice” is heard in civic debates.

Note that there’s a further opportunity to discuss the book at an upcoming event, “Campaigning for Edinburgh” – A Conversation with the Authors, on Thursday, 6 Nov, 18:00 at Augustine United Church.

Like Loading…

Related