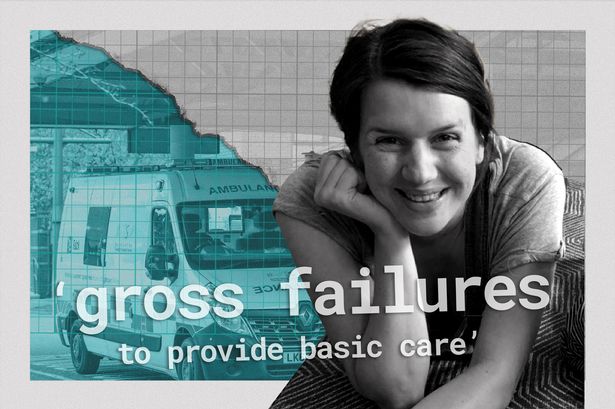

SPECIAL REPORT: After the deaths of Jen Cahill and her newborn daughter Agnes, a Manchester court heard of catastrophic errors and fatal misunderstandings in maternity care. The deaths of Jen Cahill and her daughter, Agnes, after a tragic home birth were contributed to by ‘neglect’, ‘catastrophic error’ and ‘gross failures to provide basic care’(Image: MEN/Handout/2025 Getty Images)

The deaths of Jen Cahill and her daughter, Agnes, after a tragic home birth were contributed to by ‘neglect’, ‘catastrophic error’ and ‘gross failures to provide basic care’(Image: MEN/Handout/2025 Getty Images)

The room falls silent. All except for the gentle rustling of tissues being clutched in their plastic packets.

It’s an agonising wait for an apprehensive, full courtroom. But that wait is only 20 minutes before the final chapter of this case begins.

Others in this courtroom have been waiting more than a year for answers.

Senior coroner Joanne Kearsley files through the door and sits at her bench, raised in front of the crowded court packed with the family and friends of a beloved mother and her newborn baby.

I’ve spent seven years as a reporter covering Ms Kearsley’s cases at Rochdale Coroners’ Court, and have long seen her spending her days as a stoic leader of proceedings. She’s unflappable in her questioning of deaths caused by injustice, kind in supporting families through their most difficult moments.

But three hours later, I watch as the coroner fights tears as she tries to speak – recording the unfathomable loss of that tiny baby girl, Agnes, and her mother, Jen Cahill, aged just 34.

“Rob,” her voice wavered, addressing Jen’s husband and Agnes’ dad.

“I think it will be hard for any of us to ever understand, and I cannot find the words to describe the absolutely horrific nightmare you endured in a very short space of time on June 3, 2024, and in the days that followed.”

Then, a crushing blow.

“As the situation is today, I cannot help but worry that unless change is made, then another family will potentially endure the agony which Rob and Jen’s family has faced.”

Jen knew some of the concerns associated with choosing to give birth at home, with her medical history putting her at higher risk during delivery.

And she was cared for by Manchester University NHS Foundation Trust (MFT) – the largest trust of hospitals in England.

If these deaths can happen to a family under the care of one of the most well-resourced trusts in the country, what comes next?

Jennifer Cahill(Image: MEN/UGC)

Jennifer Cahill(Image: MEN/UGC)

Jen and Agnes died after a tragic birth at their family home in Prestwich in the early hours of that June morning.

After a long and difficult labour through the night, Agnes was born not breathing, with the umbilical cord around her neck.

Jen suffered a perineal tear, two postpartum haemorrhages, and went into cardiac arrest.

On Monday, October 26, 2025, the coroner determined that both deaths in the following days were contributed to by ‘neglect’, ‘catastrophic error’ and ‘gross failures to provide basic care’.

Jen Cahill knew some of the risks of delivering her second child. The first time, Jen suffered a postpartum haemorrhage, an episiotomy, a tear, and lost enough blood to warrant a transfusion.

She was also a carrier of group B strep, which can spread to babies during delivery and cause problems like meningitis.

Her first child went on to develop sepsis after being born, recovering later.

She felt midwives often had too many mothers to help. She felt she was left alone during a long and painful labour, where her first baby was known to be large and in a very position in the womb.

Jen and her husband shared fears that staff attending to her during the labour kept changing – meaning they had to explain information multiple times, creating confusion.

The court heard that Jen thought that having two midwives present through a birth at home, just attending her, could avoid the things that previously ‘traumatised her’.

Jen also knew that she had been advised a number of times by midwives and doctors to have a hospital birth for her second child.

She would have faster emergency help if she had another haemorrhage. She would also have IV medications that would help stop bleeding and guard against strep, not available for a home birth.

(Image: Manchester Evening News)

(Image: Manchester Evening News)

But the inquest revealed that Jen had received mixed messages of just how at risk she was.

During an appointment, one consultant ‘correctly’ graded Jen’s pregnancy as low risk. The doctor decided Jen would be cared for by community midwives as the pregnancy progressed – rather than care by consultants if she had been a high risk.

The consultant gave evidence that she ‘assumed that the patient understands, whilst her pregnancy could be a low risk, she may be at a ‘high risk’ in terms of the delivery’.

Doctors and midwives also gave evidence that the priority in discussions around where to give birth is often on giving women the freedom to choose.

For Jen, that’s how ultimately fatal confusion and misunderstanding grew.

“One can see why this misunderstanding arises since many women may understand the term ‘pregnancy’ to incorporate the entire process from pregnancy through to labour and delivery of a child,” said the coroner.

“This is incorrect. Pregnancy and labour are distinct processes and carry different risks.

“In Jen’s case there was no risk attached to her being pregnant, the risk to Jen was in respect of the delivery of her child.”

Jen was not inflexible about the home birth and ‘there is no suggestion that she was reckless’, said the coroner.

She had indicated she would go to hospital if the home delivery service wasn’t available when she went into labour, and was taking a maternity bag out with her in case it started while she was out of the house.

However, the coroner determined: “Jen believed that the description being given to her, in general terms, was that she had a low risk pregnancy.

“Jen was aware of a described risk of infection to her baby as she was a group B strep carrier that she was also aware of [the consultant’s advice for preventative medication] due to her previous postpartum haemorrhage.

“But beyond these risks, I do not consider Jen viewed her pregnancy or more importantly the delivery of a child as one where there was an overtly increased risk.”

Senior coroner Joanne Kearsley(Image: Rochdale)

Senior coroner Joanne Kearsley(Image: Rochdale)

A plan required in higher-risk delivery cases going against doctors’ advice was never done. The in-depth, two-hour discussion should have created a plan ‘crucial’ for both the woman and attending midwives.

“An ‘out of guidance’ care plan… should be an opportunity to explore fully with a woman what has happened in any previous pregnancies, to explain why certain advice was being given and to explore options on all topics as well as any worries or concerns a woman has,” said the coroner.

Jen was never invited to discuss with a doctor ‘her reasons for wanting a home-birth; of other venues that were available for labour and delivery in addition to the option of hospital; an exploration of any fears that she had which were influencing her decision-making around a home-birth’.

“This meant that the personalised risks associated with Jen having a home-birth were not fully explored,” added the coroner

“From the time Jen indicated she was considering a home-birth in February 2024, her antenatal care lacked any active inquiries, was based on assumptions made by midwives and was perfunctory.

“The most critical of appointments with a senior midwife to complete the most important guidance document, an out of guidance care plan, was simply overlooked and forgotten.

“This was a catastrophic error and a gross failure to provide basic medical care.”

Jen was also never advised of the instability of home birth services. Pregnant women are not advised of how thin on-call staffing can be overnight, when Jen went into labour, the court heard.

They are also not told the background of the midwives who might be sent out to assist them during their labour. In Jen’s case, the two midwives had both done 12-hour shifts before the home birth.

One of those attending midwives, who had never resuscitated a baby, told the court ‘we’re not trained’ for that rare combination of higher risk home birth – with all home births only making up a very small percentage of births in general.

The midwife gave evidence that concerns had frequently been raised to senior leaders at the Manchester hospital trust about the rising numbers of higher-risk women opting for home births.And just like Jen, the two midwives found themselves blind to risks. Neither had ever been informed prior to their arrival at the Cahill home of the documented concerns about complications for Jen during the delivery of her child.

“I heard a lot of evidence in relation to the increase of home births and the right of a woman to choose where she has her child,” said the coroner.

“But I also heard of a complete absence of any national guidance, and the incredibly difficult position this is placing many trusts, and more importantly the increasing challenges for community midwives.”

The deaths of Jen and Agnes have prompted ‘a huge overhaul’ of maternity services in the Manchester.

Kimberley Salmon-Jamieson, Deputy Chief Executive and Chief Nursing Officer for MFT, said: “The trust accepted at an early stage that there were serious failures in the care provided to Mrs Cahill and Agnes for which we are truly sorry.”

The trust said it is ‘committed to learning’ to ‘make services safer’, explaining that the ‘homebirth service has been remodelled’, shaped by internal and independent investigations. The trust says it will also be examining the inquest conclusion for further actions.

But it’s change that, devastatingly, wouldn’t have happened without these deaths. Change that, worryingly, can’t be done elsewhere, said the coroner.

The court heard from Professor Edward Johnstone, the clinical head of division for maternity services, and Esme Polshaw, the head of midwifery, at the trust.

National data about the safety, complications and outcomes surrounding home births is so lacking and out of date that ‘women cannot make an informed choice’ about the safety of home births, they said.

“The evidence available is quite out of date. And it is very difficult as a lay person to find that information and make that judgement,” said Prof Johnstone.

“I don’t think there’s a national leadership recognition [that a similar overhaul needs to be made across the country].”

In their view, some areas in England should not be providing home birth services at all.

Rural places, especially, have much smaller teams of midwives than a metropolitan hub like Manchester which attracts NHS staff.

The nearest hospital might be hours away, unlike the offer of three maternity units in Manchester borough alone.

The cost of this niche service is also high, said the coroner. NHS services in more disparate, less populated areas do not have the budget of those that Jen used, operated by largest hospital trust in the country in Manchester.

“This is not something that should be provided by every trust. If you’re a tiny trust, I don’t see how you can maintain that service, and it shouldn’t be provided as an add-on to community services if it’s going to be provided” explained the professor.

“It needs to be a specially commissioned service with a political decision as to who it’s going to be maintained and funded by.”

“Given the evidence I heard around the increasing number of home births, particularly at the request of women who would previously not have considered them, i.e high risk women – I remain deeply concerned,” added the coroner.

“I would agree with Professor Johnstone – some of the information women are not provided with one wonders how women can make an informed decision.”

North Manchester General Hospital was the location of Jen’s first birth, and where she and Agnes were rushed to after the tragic home birth(Image: Manchester Evening News)

North Manchester General Hospital was the location of Jen’s first birth, and where she and Agnes were rushed to after the tragic home birth(Image: Manchester Evening News)

A harrowing 15 months and a gruelling two-week inquest comes to an end. Many in the courtroom break down in exhaustion.

The utter devastation is a black hole that engulfs the ability to find words, but the tearful coroner makes an offering.

“When I consider all I have heard about your daughter, Agnes, I recalled a quote… I’m sorry – it’s Shakespeare,” Ms Kearsley says.

The courtroom lets out a humoured sigh, searching for a chink of light.

“‘Though she be but little, she is fierce.’ Agnes certainly put up a fight to survive.

“It may be of a very small comfort, possibly no comfort, but Jen and Agnes are making a difference to women and professionals in Manchester today.”